From the exhibition Divine Violence.

Among the diverse counsel offered by the Bible, there is wisdom on booze (“And be not drunk with wine, wherein is excess, but be filled with the Spirit,” Ephesians 5:18) and advice on tattoos and piercings (“You shall not make any cuts in your body for the dead nor make any tattoo marks on yourselves,” Leviticus 19:28).

The Bible even offers instruction on vandalism. “Catch the foxes for us, the little foxes that spoil the vineyards, for our vineyards are in blossom,” reads a verse from the Old Testament’s Song of Songs, also known as the Song of Solomon.

Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin are little foxes. About four years ago, this London-based photographic unit, childhood friends since their early youth in 1970s Johannesburg, patiently and methodically set about vandalising – or desecrating – the Bible.

The outcome of their labour, which was prefaced by a whole summer of scripture readings, is on view until April 11 at the Goodman Gallery in Cape Town.

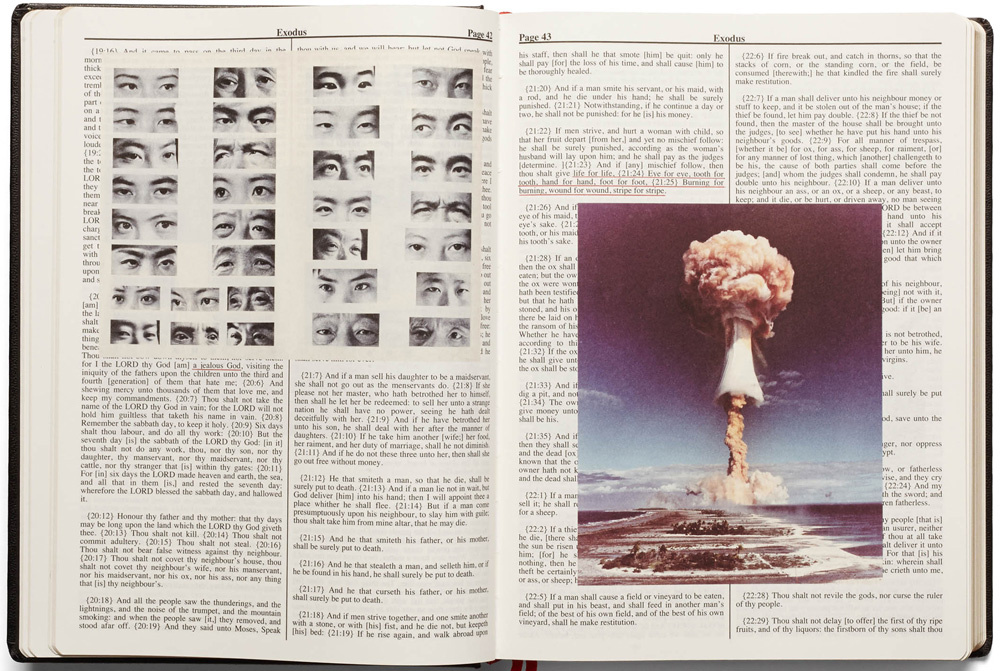

Spread over six walls, beginning with Genesis and ending at Revelation, their exhibition Divine Violence offers a sense of what the pair’s East End studio looked like as they worked on creating their extravagantly illustrated version of the Bible for publication as a book.

Holy Bible is the duo’s 10th book. Published two years ago, it won the 2014 Infinity Award for publications at the International Centre of Photography in New York. At the Goodman it is shown in 57 discrete frames, roughly corresponding to the 66 books in the Bible.

A full set of the limited Bible prints is available for R3.95-million. A standard hardback version of the King James Bible costs less than R100, but Broomberg and Chanarin’s illustrated version of the King James Bible costs over R1 000.

Felling warhorses

Their book differs from the Church of England’s official English translation of the Bible in two ways. Take the page from Ephesians promoting abstinence. Rather than focus on the warning against debauchery, the duo underlined chapter five, verse 22: “Wives, submit yourselves unto your husbands.”

That’s not all. Placed over the biblical text on the facing page is an uncaptioned photo of a caltrop, a sharpened spike used to fell warhorses.

This unusual strategy is repeated throughout their Bible: fragments of text are underlined in red and accompanied by cryptic images of conflict, dancing, bizarre sex, murder, sexual prowess, suicide, magic tricks, Nazi instruction, genocide, play and picnicking.

Inspired by their encounter with German playwright Bertolt Brecht’s personal Bible, which he extensively annotated and illustrated with pictures, they set about illustrating their own Bible with the same commitment and eccentric purpose as medieval monks.

Although the Bible is notionally a sacred text, European monks were sometimes prone to adding their own visual flourishes. The Smithfield Decretals, a 14th-century Bible written in Italy but illuminated in England, includes drawings of two rabbits in the act of killing a man and a knight in armour squaring off against a giant garden snail.

Broomberg and Chanarin’s Holy Bible uses photos instead of drawings. In the manner of their previous book, War Primer 2, a compendium of news images documenting the “war on terror” – published in 2012 and awarded the prestigious Deutsche Börse Photography Prize in 2013 – they used archival news images to illustrate their Holy Bible.

Initially they wanted to work with a London collector’s hoard of expensive collectable photos; he declined. So they approached the Archive of Modern Conflict, an unconventional photo archive in North London owned by David Thomson, the Toronto chairperson of Thomson Reuters and a well-known art collector.

“They said ‘yes’ in about five minutes to our idea,” said Chanarin during a brief visit to Cape Town.

Broomberg and Chanarin’s Holy Bible is both a photo book and a bizarre update of the time-honoured tradition of the illustrated Bible. As a photo book it offers further evidence of their love-hate relationship with news photos. Formerly the editors of Italian photo magazine Colors, the duo’s falling out of love with news and documentary photography is well known.

In 2008, after serving as jury members at the World Press Photo awards, they published a controversial editorial dismissing photojournalism as “a photographic genre in crisis”. Over the past half-dozen years their own photography has become increasingly critical and cryptic, and often features other photographers’ work among their own.

Holy Bible is no exception. It includes a wealth of amateur photography and a selection of photos by a who’s who of international photography, but none of Broomberg’s or Chanarin’s own work.

Capa, uncredited

The book of Genesis, for instance, reprints two lesser-known photos by photojournalist Robert Capa. The uncredited photos show Federico Borrell García, the 24-year-old millworker and Spanish loyalist militiaman, shortly after he was felled by an enemy bullet at the Córdoba front during the Spanish Civil War in 1936. “Let it be for a witness,” reads one of two underlined verses above Capa’s image.

South African scenes also appear in the book. A page from Isaiah showcases Ian Berry’s action shot of people fleeing police fire outside the Sharpeville police station in 1960. Like Ernest Cole’s well-known photo of naked black miners lining up, arms raised, for medical inspection, which appears in the first book of Kings, Berry’s photo is also uncredited.

“We have sinned, and have done perversely, we have committed wickedness,” reads an underlined text from the page on which Cole’s photo appears. For some it may well describe their act of creative appropriation.

“The relationship between the text and images varies,” offered Chanarin of the duo’s organisation of image and text. “Sometimes the text is very descriptive and straightforward – here is a piece of text taken out of the Bible that really explains a picture – and at other times it complicates things, or has a more poetic relationship.”

Although explicitly inspired by Brecht, Chanarin said that their decision to push ahead and work with the Bible format also derived from an insight while digging through a hoard of photos by the collector who rebuffed their initial proposal.

“It struck us that there was something biblical about his ambitions,” said Chanarin, who was born in London to South African parents. “It wants to describe everything about the world, about being born and dying. There is something about the whole project of photography that wants to encapsulate everything about human life.”

The grim undertone of the 800-odd photographs – they include two explicit photos of a man in a Hitler mask having heterosexual sex and many scenes of death – is purposeful. In the only textual embellishment to Holy Bible, Israeli philosopher Adi Ophir explains why.

“It is through catastrophe that he [God] reveals himself and makes himself known in public, thus turning himself into the object of prayer, hope, salvation and mercy,” he writes in his essay Divine Violence.

“God’s mode of utterance is catastrophe, violence and punishment,” said Broomberg during his Cape Town visit. “What we recognise is photography’s commitment to those same things. That is what it follows: the oddity, the violence, the pain. It seemed like the perfect pairing.”

Although the Cape Town exhibition of their sundered Bible has not drawn any criticism from Christian groups, according to a Goodman Gallery representative, it still represents a volatile proposal.

Raped by a priest

In 2009, Zimbabwe-born artist Anthony Schrag – he recently collaborated on an art project with residents of three inner-city Johannesburg neighbourhoods – invited Glasgow’s lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex community to “write their way back in” to the Bible at an exhibition in a public museum.

“Queer, Christian and proud,” responded one person. Another offered a parable: “Holy figures hide behind their religion to hide who they are. Once you have been raped by a priest, maybe you understand, as I have.”

The intervention was picked up by the tabloids and prompted heated feedback.

“We have got to a point where we call the destruction of the Bible modern art,” said Andrea Williams of the Christian Legal Centre. “The Bible stands for everything this art does not: creation, beauty, hope, regeneration.”

Pope Benedict XVI was more emphatic: he described Schrag’s project as “disgusting and offensive”. A representative for the leader of the Catholic faith added: “They would not think of doing it to the Qur’an.”

“It is hard to argue this project out of a trite juvenile gesture where you’re whacking some volatile images on a text that everyone has a very personal and emotional attachment to,” conceded Broomberg, who was born in Johannesburg in 1970 and is a year older than Chanarin.

He nonetheless countered that the project was the outcome of a significant investment of time, initially in reading the Bible and later in pairing the archival images with biblical passages.

He added that the book, which ends with an abstract photo retrieved from a damaged negative, offers a meditation on how “fucking important” images are in understanding violence, in particular the United States’s physical as well as image wars in the Middle East.

“It is about photography as this kind of monster,” remarked Broomberg. “We totally subscribe to that.”

Sean O’Toole is a freelance writer based in Cape Town