Painting with words: Eliza Kentridge has produced a collection of poems filled with integrity and beauty.

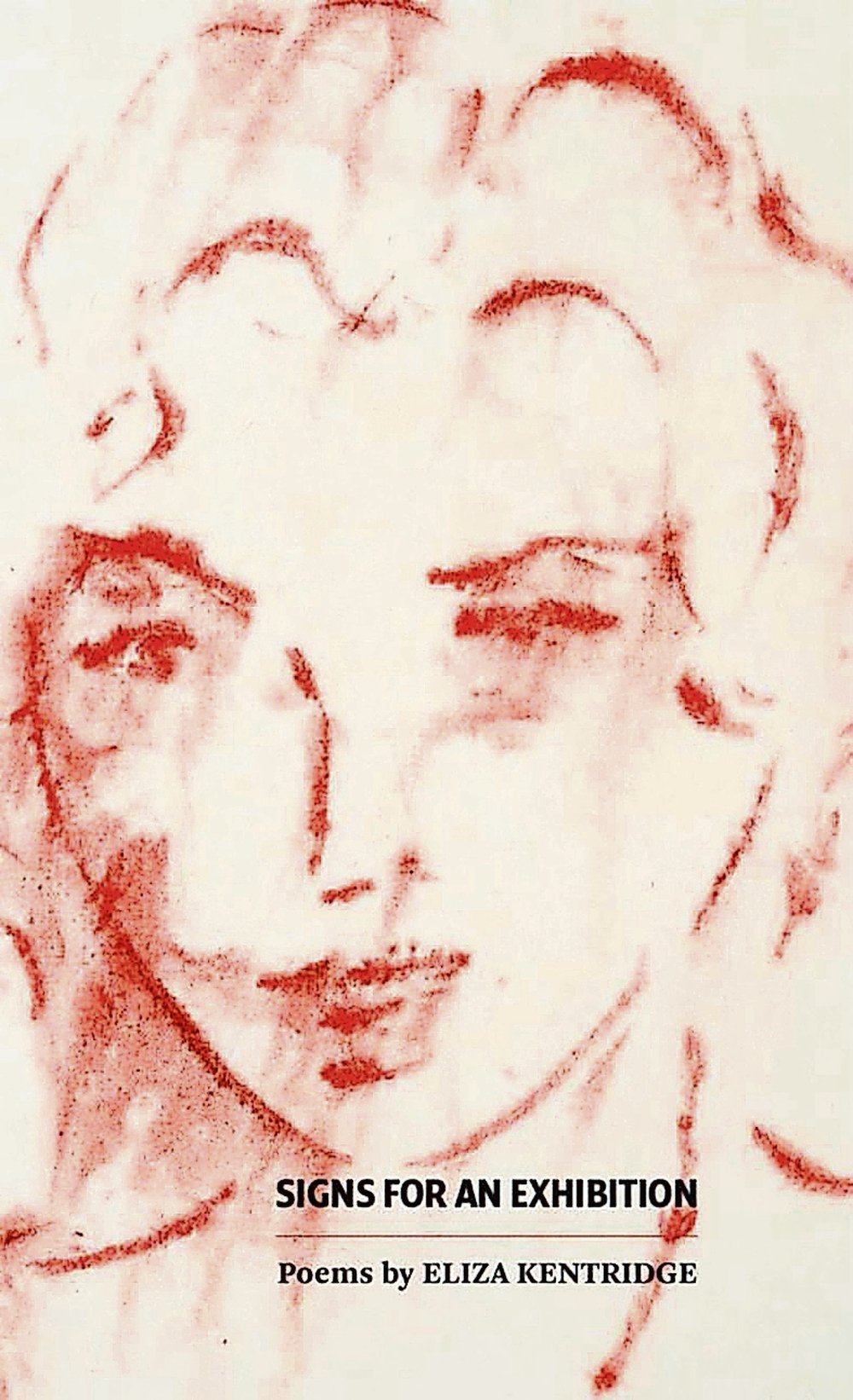

SIGNS FOR AN EXHIBITION

by Eliza Kentridge (Modjaji Books)

Eliza Kentridge was born in Johannesburg around the time that her father, Sydney Kentridge QC, defended Nelson Mandela against the charge of treason. She was a teenager when he represented Steve Biko’s family at the inquest into his death.

Against this momentous backdrop, in contrast to the work of her brother William, whose art focuses on overtly political themes and other big questions, Eliza Kentridge’s work is internal and modest – “quieted”, as she might say.

This collection of poems – her first – explores a marginalised subject: how life in the old South Africa really was for those of us who knew about the horrors of apartheid but did not suffer them. Although her parents were, to quote from one of the poems, “cross” with the government they opposed so steadfastly, they also went on family holidays, looked after the pets and read to their children from English books – as the young Eliza played in the garden, worried about the shape of her legs, and fell in and out of love.

The ethical questions arising from such simple autobiographical facts haunt this collection of poems, which reveal the structure of the mind with unusual clarity. The author describes her current life in coastal Essex in Britain, filtered through the remembered Johannesburg of her girlhood, charged by the erotic excitements of her maturing body (“prickly grass fucking my soles”), constantly observed by an inner critic who questions her every move.

The emphasis falls on the latter, her superego, whose voice is capitalised: “NEATLY, ELIZABETH”; “DO YOU KNOW HOW LUCKY YOU ARE?”.

The same voice gives the collection its title: Signs.

Signs convey warnings and prohibitions, instructions and directions. But they also exist for good reasons. This helpful aspect of the superego is most evident in silent dialogues between Eliza and her mother (the indomitable Felicia Kentridge, founder of the Legal Resources Centre, who died as this book went to press).

The fact that her mother was no longer able to speak when the poems were written, due to a neurodegenerative illness, gives these conversations a special poignancy. They are grateful and reparative: “You dropped a dish/ Your hands let go/ …/ We wanted to reverse the action/ Put the dish together again/ Smooth the ragged edges back to perfection/ To pick up your tears and put them back in your eyes.”

These lines reflect what psychoanalysts call the depressive position. But in another poem the superego retorts: “Risible/ Derisory/ CHILDREN NEED NOT THANK PARENTS FOR HAVING THEM.”

These internal struggles are private and personal but they pose a question of universal significance: When born into such circumstances, how does one live one’s life? Kentridge’s answer is relentlessly honest. She writes about the immediate realities of family and place, deliberately, almost apologetically, shifting emphasis away from the big abstractions that did not actually happen to her – although she was acutely aware of them.

In doing so, she invokes Psalm 131: “O Lord, my heart is not lifted up;/ my eyes are not raised too high;/ I do not occupy myself with things/ too great and too marvellous for me./ But I have calmed and quieted my soul,/ like a weaned child with its mother;/ like a weaned child is my soul within me.”

In her Sign Poem 10: “Repeat after me/ BUT I HAVE STILLED AND QUIETED MY SOUL/ But I have stilled and quieted my soul/ That’s good.”

The reference to David’s psalm is but one of many literary borrowings scattered through these poems, giving a muted erudition to the images that make up her personal iconography. As happens with every human mind, the defining images of her inner life appear fleetingly and then reappear across multiple disjunctions, slowly revealing their meaning to the reader.

For example, the image in one poem of a birdlike 10-year-old self “hopping about with hopeful, uncomplicated energy” links associatively through avian images in several other poems with the hummingbird shape of an atrophied brainstem – a pathological hallmark of the disease that afflicted her mother.

The full title of the collection is enigmatic: Signs for an Exhibition. This reminds us that Kentridge is a visual artist too. She has for many years sewed applique drawings and sculpted little terracotta figures, depicting – like her poems – images from everyday and domestic life. Her previous work blurs seamlessly with this poetry; indeed, culminates in it. It is not difficult to imagine her poems as visual art.

This suggests another aspect of the life of the mind. Alongside the veridical scenes from memory, an imaginary world of fantasy sporadically unfolds.

Thus in Sign Poem 19 the little girl Eliza watches a cat give birth to mice; in Sign Poem 24 a train journey to London terminates in a fantastical imaginary landscape; and in Sign Poem 40 the motorcade at Nelson Mandela’s funeral – as seen on British TV – morphs into a Pharaonic procession down the Nile. As I read this last poem, through its blinding sunlight over water, I could swear it was painted by Turner.

But the special quality of these poems has nothing to do with such grand claims. By stilling and quieting her soul, Kentridge has produced a work of great integrity and beauty. Her intimate reflections upon ordinary aspects of life are achingly true – anyone can see that – and the result is extraordinary. The defining feature of these poems is, dare I say it, their femininity. What is it with these Kentridges? How many kinds of genius can one family produce?

Mark Solms is a professor of neuropsychology at the University of Cape Town and president of the South African Psychoanalytical Association.