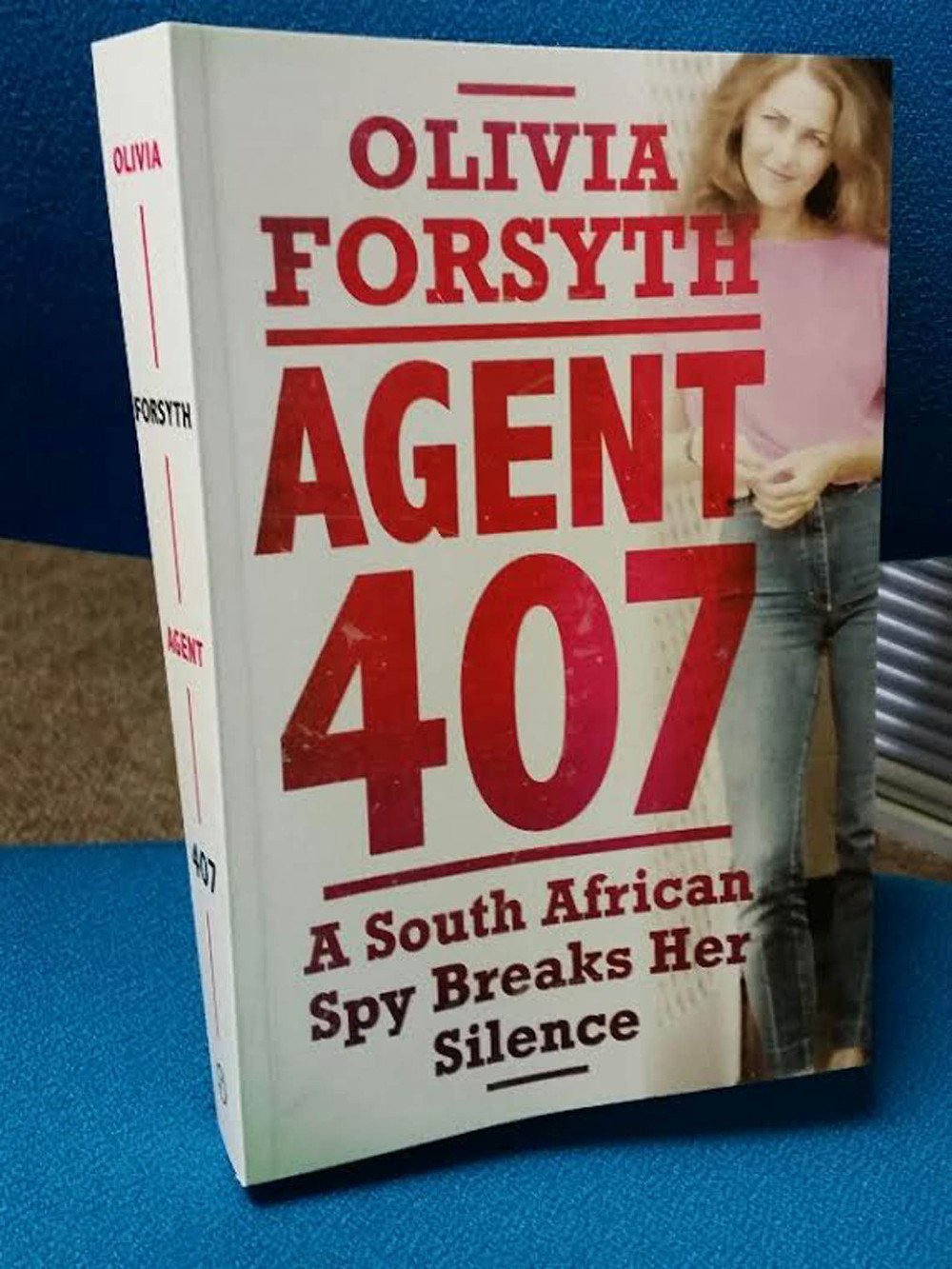

Olivia Forsyth as she is today

Nigh on 30 years later, nobody can reliably recall whether there ever was a physical medal manufactured, a handmade lapel button or two, perhaps. But in the second half of 1988 there was at least an imaginary badge of honour bestowed on some in leftist circles at Rhodes University, reading: “I did not sleep with Olivia Forsyth.”

Not everyone received such a badge. Some had, indeed, been literally intimate with the enemy. Many more – seemingly everyone involved in activist politics of any kind in Grahamstown at the time – had been taken in by the woman who had been integral to various protest campaigns even while she was an officer of the apartheid regime’s brutal Security Branch police unit.

When Forsyth chaired a mass meeting to expose the prevalence of police spies on the campus, nobody blinked an eye.

And sex was the go-to metaphor when it came to betrayal and intelligence infiltration because, as one participant now puts it, there was rather a lot of it going around.

So when Forsyth’s memoir, Agent 407: A South African Spy Breaks Her Silence, is released in August there will be two groups of people keen to read it: those checking to see whether they were kissed and told on, and those looking to see who of their comrades can be made fun of for having fallen prey to the apartheid honeypot.

Both groups will be disappointed. After wading through magniloquent descriptions of continental climatology (a sky blue “with an intensity that seems reserved only for the heart of Africa”; a sun that sets “in a way that only the African sun can”), and interminable descriptions of childhood (her reformed-nun mother was “beautiful”; her storyteller father was “handsome”; there were many siblings and best friends and the occasional pet baboon), they will find a promise of no sexual shenanigans in the remaining two-thirds of the book.

As an officer in the police, Forsyth writes: “I was forbidden to have any affairs with the enemy. The honeypot role was reserved for sources who were not actual members of the force, but paid informants.”

The no-sex promise is mercifully broken with the revelation that sex did play a role in her journey from apartheid spy to ANC collaborator-cum-detainee and back to apartheid apparatchik again, just as the salacious 1980s gossip had had it.

But the details are scant, the partners (her initially repellent first spymaster, an ANC member in exile, and a one-time editor of this newspaper) are relatively unimportant and the examination of the relationships’ importance is nonexistent.

After Forsyth was outed as an apartheid spy who had defected to the ANC, the police built a propaganda campaign around her.

In other respects the book offers much the same combination of disappointments. Described by her publishers as “South Africa’s most notorious apartheid spy”, Forsyth manages to recall the music she danced to and what she served at parties, but not details of police raids by her Security Branch colleagues on the leftist publications with which she worked. She can offer a comprehensive list of what she read in an ANC prison but can’t describe exactly how she betrayed her student comrades.

The highlights of her spy career appear to have been stealing a set of car keys so duplicates could be made and mistakenly moving a bright red flowerpot from one window to another.

For those who are still puzzled by Forsyth many years later, this is most unsatisfactory.

“I think it is just endlessly fascinating in hindsight,” says Bridget Hilton-Barber, a writer who went shoulder to shoulder with the supposedly revolutionary Forsyth in the 1980s and who features extensively in the book. “For instance, how do you reconcile being party to atrocities while spying on your friends? I’m just interested in the cognitive dissonance she must have felt.”

Hilton-Barber cites an incident in which Forsyth drove a badly burnt woman, who later died, to hospital. She was the victim of a petrol bomb attack either by the Security Branch or at the behest of security forces, of which Forsyth was an employee.

“I just think it is the most paradoxical or bizarre thing,” says Hilton-Barber. She dismisses as “rubbish” Forsyth’s claim that she worked for apartheid police in order to become a double agent in service of the ANC.

Perhaps more paradoxically, while Hilton-Barber and Forsyth’s other fellow activists remain angry with her – and livid that she will profit from telling the story of her betrayal of their cause – her book will find a sympathetic reception from other struggle veterans.

“A lot of people were very hurt by her,” says former intelligence minister Ronnie Kasrils, to whom Forsyth in part dedicated her book, on why he declined to write a foreword to it. “But I feel there was a reform within her, that she was genuine when she said her heart had always been in the right place. I think her motives were pure.”

Like Kasrils, former Mail & Guardian editor Howard Barrell had not yet seen Forsyth’s book this week. But he had long viewed her with sympathy, he said, even after having to go into hiding when she returned to apartheid’s bosom following an affair during which he had introduced her to the ANC, thereby compromising his own security.

“I was deeply shocked and very hurt to find out that she was a South African agent, but that does not alter my regard for her,” Barrell said. “I think she was led into a series of political relationships with the South African [apartheid] system against her will. I don’t think she ever believed in what she was doing in working for the security police.”

The spy who lied to everyone

Olivia Forsyth was recruited as a Security Branch officer at the age of 21 and sent to Rhodes University to infiltrate pro-ANC structures. She was deeply involved in student politics, and led various campaigns opposing the apartheid regime.

In 1985 she approached the ANC in Zimbabwe and offered to be a double agent. Instead, she was interred in the infamous Quatro prison camp in Angola for several months before the intervention of Chris Hani and Ronnie Kasrils saw her transferred to a safe house in Luanda, to await an exchange for ANC prisoners in South Africa.

Forsyth, who was born in South Africa but held a British passport, escaped the ANC and holed up in the British embassy in Luanda. While negotiations were under way to allow her to leave the country, her story was leaked and made global headlines.

On her return to South Africa, she claimed that her defection to the ANC had been a hugely successful ploy by the Security Branch to infiltrate the ANC.

She has since maintained that the claim of a false defection had, in fact, been a misinformation campaign.

Forsyth lives in Britain. She will launch her book in South Africa in August.

- Article updated with a clarification from Ronnie Kasrils below.

Letter from Ronnie Kasrils to the editor, on August 2 2015

I refer to your report on Olivia Forsyth and comments from me among others.

Mine was a fairly long conversation with your correspondent and if he thought I had stated Olivia Forsyth was of “pure heart” that is incorrect. I never trusted her, nor could forgive her role as enemy agent and the harm she caused, but during her period of detention I thought it possible that she was changing her ideological views. After all rehabilitation and education of detainees had that as an objective.

Chris Hani and I were of the same view that detainees in ANC custody should be as decently treated as possible in a difficult context.

We did not wish to see women detainees incarcerated at Quatro which is why we had some five or six removed to house detention in Luanda — Forsyth among them.

We hoped to exchange her for MK prisoners on Apartheid death-row.

Instead the opportunity to escape presented itself which she took with alacrity. Prior to the decision to detain her I for one was prepared to test her offer to act as our double-agent. You win some you lose some in that game. I have not yet read her book and her true position remains her secret.

Ronnie Kasrils