Researchers have revealed details of the recently discovered Homo naledi – a species with characteristics eerily similar to humans.

They moved the bodies in one at a time, from the old with their worn teeth to newborn babies. If they had been modern humans, the Dinaledi Chamber would have been called a burial site. But the creatures are not human.

Homo naledi (“naledi†means star in the local Sotho language) is a new species and an ancient human ancestor, researchers claim. Excavated as part of the Rising Star expedition in South Africa’s Cradle of Humankind in 2013, the species was described for the first time in scientific papers published on Thursday.

H. naledi is strange mix of modern and archaic: a skull big enough to fit a small brain, much smaller than ours (or my clenched fist), feet that look like they could be on a modern human, wrists and hands that could belong to a tiny human but with elongated, strong fingers, perfect for climbing.

Homo naledi skull. Photo courtesy of Wits University

Standing at about 1.45m, H. naledi are taller than Australopithecus, an extinct hominid species which has been found in southern Africa, although their pelvises are both flatter than humans’.

However, critics say that the new find is an example of “species inflationâ€, meaning that the small round-shouldered creature may actually be Homo erectus, another species of already discovered hominin. But without a date-stamp attached to the collection of remains in the chamber, questions continue to hang over the find.

Disposing of the dead – a behaviour once thought unique to humans

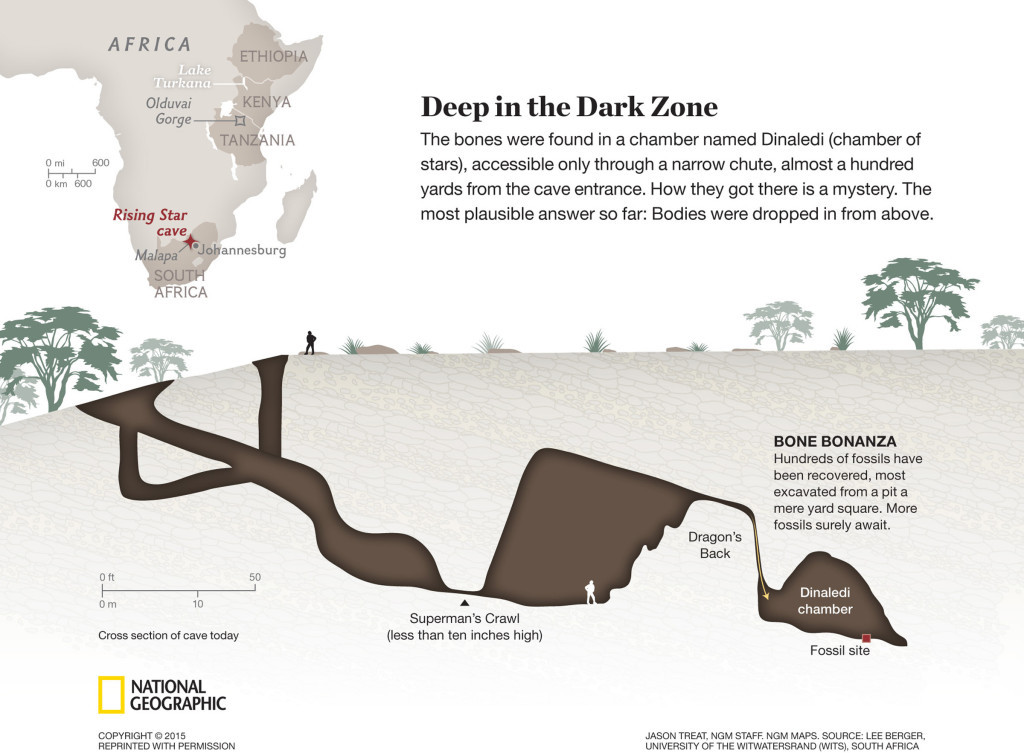

Deliberate body disposal is the researchers’ preferred theory as to why 15 hominin skeletons – and possibly hundreds more that have not yet been excavated – were found at the bottom of a treacherous underground cavern with only one entrance.

“The Dinaledi Chamber is unusual because of the large number of fossils discovered so close together in a single chamber, and that the bodies had not been damaged by scavengers or predators,†the international author team write in online journal eLife. “It also appears that the bodies were intact when they arrived in the chamber, and then started to decompose.â€

But arriving in the chamber is not an easy feat.

Located 30m below the surface and 80m (in a straight line) from the cave’s entrance, anyone entering the Dinaledi Chamber would have had to squeeze through the “Superman Crawl†which is 25cm high (less than a school ruler in length), before climbing 15m up the “Dragon’s Back†and then plummeting down a chute which is about three storeys high (11m).

This is why, at the time of the discovery in 2013, National Geographic explorer-in-residence and Wits University professor Lee Berger put out a call for “skinny anthropologists, biologists, cavers, not afraid of confined spacesâ€. Six women were chosen as the explorers who would brave this dark cave system with its high humidity. In two expeditions – one in November and one in March 2014 – they collected about 1 550 skeletal fragments belonging to 15 individuals.

Jason Treat, National Geographic, Source: Lee Berger, Wits

The image above is from the October issue of National Geographic magazine: http://natgeo.org/naledi

However, Berger says this journey would have been easier for H. naledi because they are smaller than humans.

According to the papers, “There is no evidence to suggest that an older, now sealed entrance to the chamber ever existed,†the authors write in an article titled Geological and taphonic context for the new hominin species Homo naledi from the Dinaledi Chamber, South Africa. That means that any creature entering the Dinaledi cave would have had to use the same entrance as the six Rising Star excavators.

But this issue of body disposal, if that is indeed what the Dinaledi Chamber represents, is important because it points to a level of cognition and behaviour that is thought to set humans apart from other animals.

There has been evidence that Neanderthals, thought to be our closest Homo relatives, buried their dead. If H. naledi disposed of their dead in a ritualistic way, it reduces the behavioural distance between them and modern humans.

“Unlike other southern African cave sites where hidden shafts and sinkholes acted as death traps to numerous species, there is no indication of a direct vertical passage way to the Dinaledi Chamber,†the authors, led by Prof Paul Dirks from James Cook University, write. Additionally, if the chamber had been at the bottom of a death trap – such as the one that “caught†the famous Australopithecus sediba fossils at the Malapa site, discovered by Berger in 2008 – there would be other animals.

Aside from H. naledi, the only other remains excavated in the cave were rat incisors and six bird bones, nothing yet to indicate that any other animal fell to its death. Additionally, the fact that there are no large scavenger remains in the chamber, and that none of the remains shows any sign of having been gnawed or picked over, implies that, even if there had been another path into the chamber, it would have been too difficult for animals to get there, the authors write.

The other possible causes for the deposition of the remains – which the authors dismiss – are water transport (excluded because of the chamber does not allow for a sudden flood of high-pressure water) and occupation (there were no signs of occupation or tools found in the chamber).

While the possibility that the cavern was the site of a mass death trap remains, the authors argue that “none of the bone elements studied shows evidence of ‘green fracture’, indicating lack of traumaâ€.

Criticism of the discovery

Prof Tim White, an American palaeoscientist at the University of California, Berkeley, and a critic of Berger’s work, says that the Rising Star team’s conclusions are “speculationâ€. The area excavated in the chamber is “a test pit, really, measuring only 80 x 80 x 20-25cmâ€. “Most of the bones are still buried in the cave.â€

However, the main concern with the find, according to international palaeoscientists who were not involved with the research, is that there is no date attached.

University of Zurich’s Christoph Zollikofer says: “If there is not a serious attempt to date the whole site, it is difficult to draw any conclusions. It might be an early homo [species] … but a lot of the implications depend on what we think about how old it is.â€

Asked why the fossils had not been dated, Berger said: “We didn’t feel it ethical to destroy hominin material until it had been described, and dating the specimen would mean the destruction of the material.â€

He refused to speculate on their age, saying the discussions “are based on morphology and we shouldn’t use age to contaminate that … These are the most identical hominins ever discovered.†He says that the specimens found are so similar to each other that they could even be the same family, of the same genetic line.

But the issue of adding new species to the hominin evolutionary tree is a contentious one. White says that H. naledi is more likely to be an example of H. erectus. Five H. erectus fossils, found in Dmanisi, Georgia, caused an uproar in the scientific community when they were described in 2013 because the researchers, which included Zollikofer, found as much variation between individuals in H. erectus as there are in modern humans. They argue that many of the unique species discovered in Africa – such as Homo habilis and Homo rudolfensis – are in fact part of the same species lineage.

Dating the fossils would allay some of these doubts and questions.

Still, it is a fantastic fossil find despite concerns about the lack of dating, Zollikofer says: “This Dinaledi [find] adds to the argument that human evolution didn’t occur in a single jump, but that it is something that happens slowly, slowly over time… It is fantastic that [Berger] finds new fossils in these quantities – it’s not easy to do.â€

It would appear that the discoveries do not stop with this relatively small excavation of the Dinaledi Chamber.

“We’re a species with backyard syndrome – we think we know our own backyard, but we just look past it,†Berger says.

But with dedicated explorers in the field, it is very likely that we will see even more hominin fossil discoveries coming out of the Cradle of Humankind. “We’re in for one of the greatest periods of discovery in this field,†he says.

This article was first published by Wild on Science.