Public protector Thuli Madonsela has taken IEC chair Pansy Tlakula to task over a lease agreement.

Did public protector Thuli Madonsela rely on a set of records carefully circumscribed by the department of public works in reaching her conclusion that reportedly exonerates President Jacob Zuma of blame for Nkandlagate?

When the scandal first exploded into public view last year, the department and its minister, Thulas Nxesi, claimed absolute secrecy was necessary to maintain Zuma’s safety. Not even the cost of the upgrade could be revealed.

However, on November 5 last year Madonsela demanded that the department hand over documents. Within a week the task team that Nxesi had, in the meantime, appointed to do an internal investigation arrived at the department’s Durban office, which was directly responsible for the upgrade.

There, according to an affidavit filed by the department resisting amaBhungane’s court application heard in the Pretoria high court this week, it made arrangements to “collect all the documents related to the Nkandla security upgrade”.

The resultant trove, 42 files of over 12 000 pages, according to the affidavit and the department’s arguments in court this week, was what was copied for both the task team and Madonsela’s use in their respective investigations.

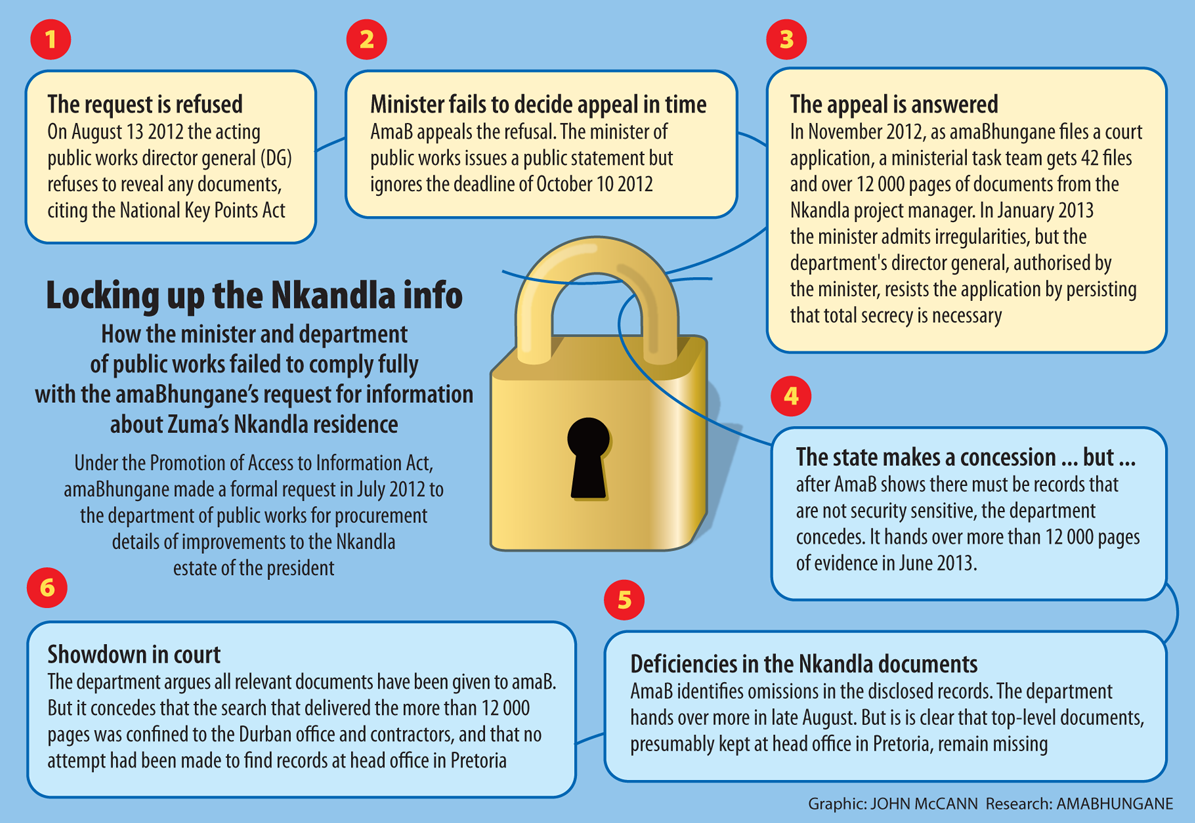

AmaBhungane, formally the M&G Centre for Investigative Journalism, had already demanded records under the Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA) in July last year.

It was met by circles of defence by the department, which raised barrier after barrier as it was forced to give ground, retreating to an ever-more limited but all the more fiercely defended core. It appears that Madonsela never breached it.

Through its court application, amaBhungane hopes to go where her office appears not to have.

Road to court

The process began with the department refusing point blank, on August 27 last year, to comply with amaBhungane’s PAIA request. “Please be advised,” it wrote, “that Nkandla presidential residence, like all other presidential residences in South Africa, is a national key point …”

As the department’s lawyers were later forced to concede, this response failed to satisfy – or even address – any of the provisions of PAIA. It appears to have been a bluff, presumably in the hope of shrugging off the request by invoking apartheid security legislation.

As PAIA allows, amaBhungane appealed to the minister. He obtained legal advice from senior counsel. But rather than use this advice to grapple with the merits of the appeal, Nxesi chose not to respond, suggesting the advice was not to his liking.

AmaBhungane’s advocate, Wim Trengove SC, this week submitted in court that Nxesi had “decided not to discharge his statutory duty” and “breached his of oath of office”. This left amaBhungane with no option but to file a high court application last November, forcing the department to defend its position on affidavit.

The new director general, Mziwonke Dlabantu, elaborated on the security defence, claiming under oath that “the documents sought are so replete with security related information that they cannot be disclosed without disclosing security sensitive information at the same time”.

This was so obvious, Dlabantu argued, that the department would seek a costs award as amaBhungane should have foreseen that the department was bound to silence by security considerations.

In March this year, amaBhungane filed what would normally have been a final round of affidavits before the matter went to court. In the interim its lawyers tracked down a civil engineer with extensive experience in public works projects. He confirmed under oath that such a project would generate many documents that had no security implications.

AmaBhungane also attached three internal documents about the Nkandla project that it had received anonymously. They betrayed no security secrets, but showed how key discussions – such as apportioning some of the costs to Zuma – had been referred to the ministry and “top management” in Pretoria.

Disclosures: the missing documents

Faced with the inevitable, the department conceded. It turned over 12 253 pages of evidence. Bar just three documents it now claimed contained actual security-sensitive information, it gave amaBhungane the same 42 files provided to Madonsela and the task team.

The about-face gave the lie to the director general’s earlier claim that the documents were “so replete” with security related information that nothing could be disclosed, and highlighted the habit of states to use sensitivity about security as a pretext for hiding embarrassment.

But on analysis, glaring omissions became apparent in the documents. Although comprehensive disclosures were made of records generated by the Durban project team and its contractors, there was almost no material from head office in Pretoria – almost nothing involving the minister, deputy minister and top officials, and certainly the president.

But there were many signs that such records must exist: references, inter alia, to other documents and interactions with “top management” and “the principal” (Zuma).

In a further exchange of letters and affidavits, amaBhungane demanded to know about the missing documents. The department’s response made it clear that this was the core that had to be defended. It claimed no further documents relevant to the request could be found.

In court this week, the department conceded it had made no attempt to locate the Nkandla files at head office in Pretoria, where the ministry and senior officials are housed. It argued amaBhungane’s request for information could be narrowly construed as relating purely to supply chain processes, which had been handled at the regional office.

What it did not say was that the evidence being sought might illuminate the actions and accountability of senior officials and the president. And it repeatedly confirmed that the records given to amaBhungane were the same as those given to Madonsela and the task team.

Media leaks about Madonsela’s report suggest that she reached similar conclusions to the task team. One article quoted sources who had read her draft as saying it painted “a picture of senior government officials bending over backwards to please President Jacob Zuma without his instructions”.

But the jury remains out until it is known what was recorded in Pretoria and not just in the regional office in Durban.

Madonsela’s office said in response to inquiries: “We cannot confirm what documents we have obtained as part of the investigation. The public protector can only reveal that information in the final report.”

Disclosure: The authors are members of amaBhungane and party to the litigation

* Got a tip-off for us about this story? Email [email protected]

The M&G Centre for Investigative Journalism (amaBhungane) produced this story. All views are ours. See www.amabhungane.co.za for our stories, activities and funding sources.