Roger Ballen’s ‘Show Off’ (2000)’. (Roger Ballen)

Roger Ballen’s book, Ballenesque, is a retrospective gallop through time or a slow journey through the evolution of Ballen’s career that has taken him from Woodstock, New York in 1969 to South Africa’s platteland and the “Asylum of the Birds”, an undisclosed home in the outskirts of Johannesburg surrounded by mine dumps.

Ballen jokes that if he were to change careers, he would be South Africa’s best travel agent, because his work has taken him through South Africa’s dorps, and from Cairo to Cape Town and from Turkey to New Guinea.

His viewpoint of the world, seen through the camera, is fundamentally psychological. So is the Inside Out Centre For the Arts that Ballen is opening in Johannesburg at the end of this year.

After spending his life adding layers to the peculiar Ballenesque aesthetic, Ballen’s universe, collection and archive have all culminated in this building. The centre is the crescendo of a 50-year journey through the furthest corners of our inner and outer world.

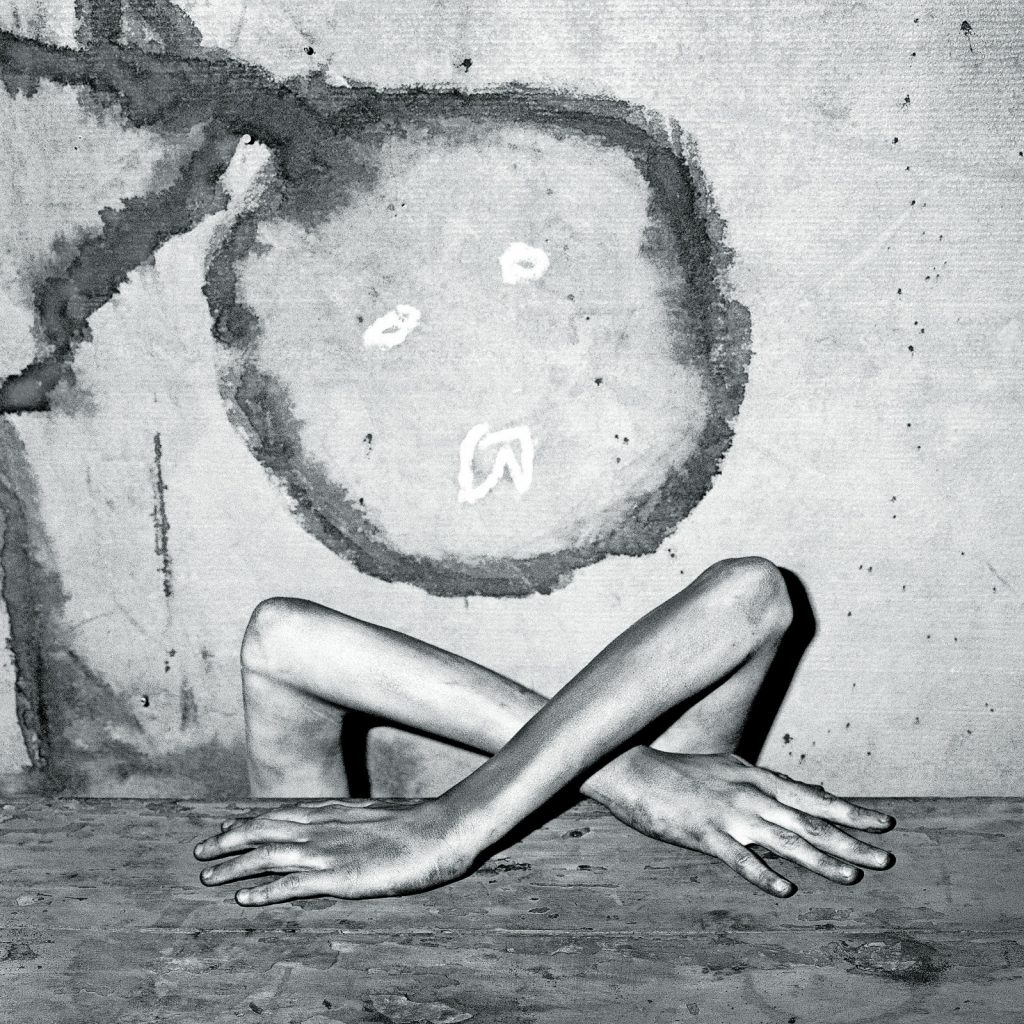

‘Mimicry’

‘Mimicry’

‘Shadow Chamber’

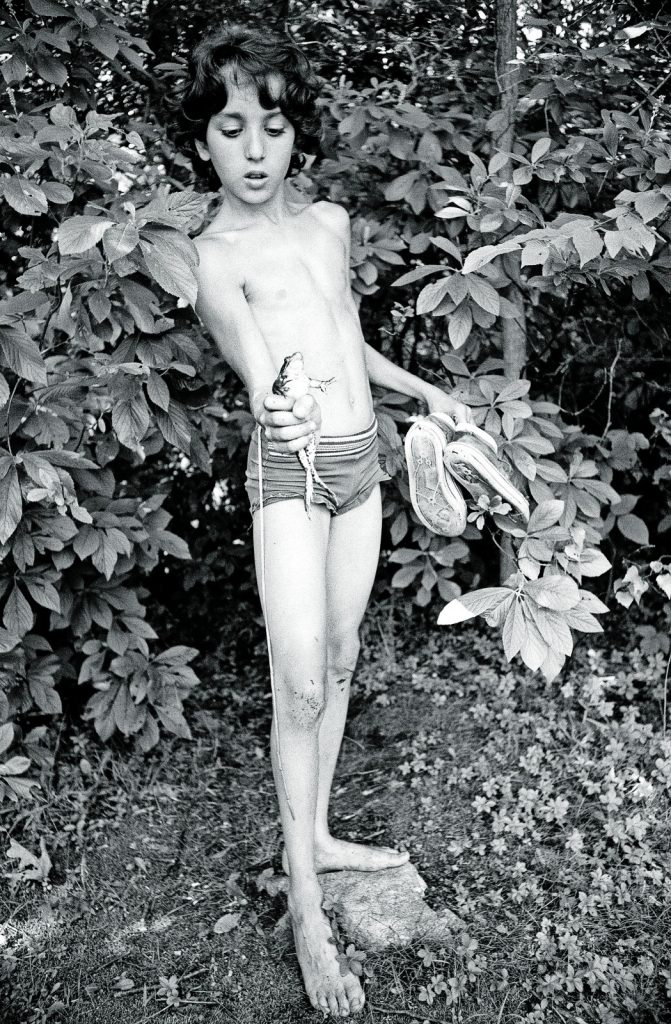

Ballen says his work has evolved from more romantic photographs — such as Froggy Boy, 1977 — to the darker aesthetic that art audiences know today. It is in 1995 that Ballen goes to the Platteland, where his monochromatic aesthetic intermingles with the raw, gritty lives led by impoverished white people during a time of South Africa’s white regime. Ballen has never returned.

The day Ballen knocks on the door of a house numbered 12 in a tiny dorp changes everything. It is at that moment when he discovers the motifs, subjects and aesthetic he has focused on since.

“The most gratifying thing is the electric shock when you see a piece of work for the first time,” says Ballen. “It’s hard to talk about; it’s something you have to ponder but you can’t explain.

“As an artist, it means you’re doing something right.”

A constant motif in his work are the walls in his images, which are covered in archaic drawings, wires that permeate the image’s forms and written annotations that speak to another meaning of the photographic subject.

‘Place of the Upside Down’

‘Place of the Upside Down’

“My work is formally organic. You won’t find anything wrong, formally, in my work. It’s the visuals that make the picture. Without this, there is no picture,” he says while pointing to the twisted wire motif in the background of the portrait, Sergeant F de Bruin, taken in 1992.

Despite photographing some of society’s forgotten people and ensuring that his subjects are well taken care of, Ballen is not a political photographer. Seen through his work in the book Shadow Chamber, his focus is an introspective of the mind, human psyche and the human condition, taking viewers to parts of their minds few dare to venture willingly.

But that hasn’t stopped others from interpreting his work as political.

Ballen’s work has been exhibited world-wide: Venice, the United States and almost in China, when his show was scrapped after the exhibitors saw the image Black Hole, which was deemed “too political” for audiences in China.

Shadow Chamber dares to question, “who is the mind?” or “where would you be without the mind?”

His 2001 work, Twirling Wires, speaks to the chaos of the mind. This image is one of Ballen’s last photographs in that mould.

From 2001, his work becomes more abstract and faces start to disappear. It’s these layers of adding and removing forms, linking drawings and portraiture and sculptural notions that takes a documentary picture into the next zone — into the universe of Ballenesque.

‘Froggy Boy’

‘Froggy Boy’

Inside Out

With a career spanning from 1967, Ballen’s work is timeless. Not tied to a single artistic movement, global event or periodic aesthetic, his work — as Ballen says — will probably outlive him. Perhaps it’s because the message behind his work existed long before the photographer and will continue to exist in the mind of humanity: the human condition. All humans from a distant Palaeolithic time to the current Anthropocene are “at the mercy of a force no one can control”.

“This is a good photograph because you see the moment,” Ballen says, with emphasis on the moment. “If you understand one thing, these images are taken at such a speed, it could stop a bullet,” he adds.

It’s a little-known fact that Ballen has had no formal education in art or photography, but in psychology and geology. It is evident that the geological notion of probing underneath and going below the surface informs his work. Ballen’s 1993 portrait of twins Dresie and Casie does just this. It gives that electric shock that is a mirror into the human’s primal state.

“The subconscious mind is complicated. I look at what motivates and controls humans,” says Ballen, pointing to the shadowy figures in his work.

“How do we get this ‘thing’ to control itself — to behave — when it’s not designed to do that?”

With wires that pervade the work and forms that work to create the picture, Ballen, with the alter ego the rat, is adding another layer to the Ballenesque world once again. He is shifting gears from black and white to colour.

Ballenesque is published by Thames & Hudson and is available for R1 330.

[/membership]