Nabbed: A Zimbabwean national caught with goods at an informal

crossing point along the South Africa–Zimbabwe border.

Dark clouds gathered overhead as an army convoy made its way along the gravel road leading in the villages.

As armed soldiers jumped off the back of their vehicles and led the way toward the dry Limpopo River bank, their movement drew the attention of illegal smugglers who quickly withdrew from the area. Some stood in no man’s land while the army kept a watchful eye on them.

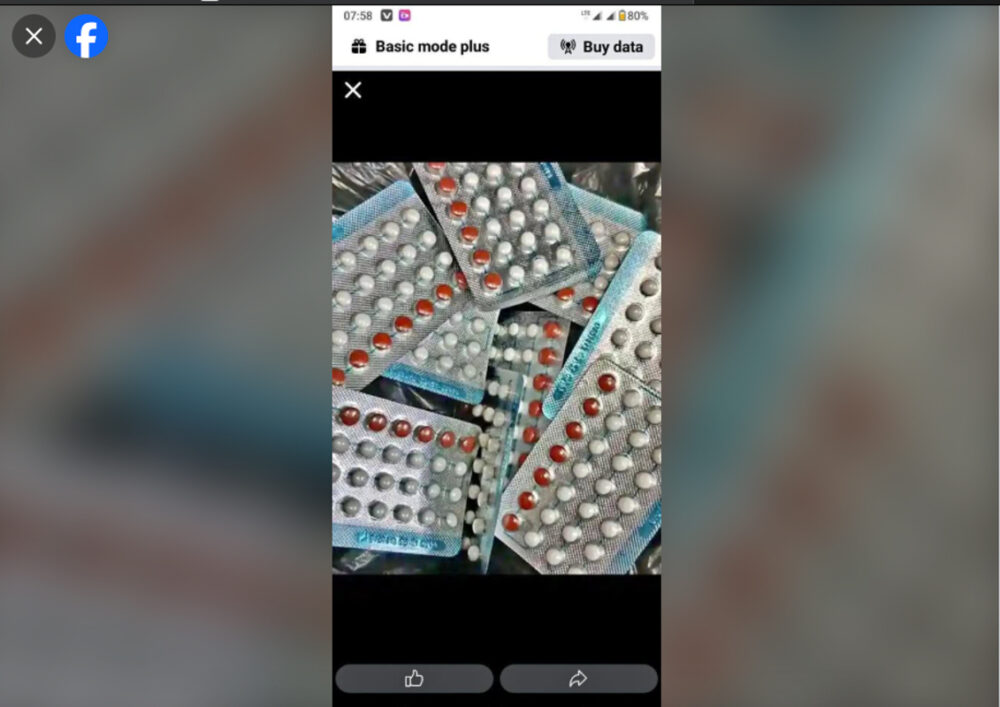

The illegal cross-border consignments include Zimbabwean contraceptive pills, which have found a market in South Africa via social media platforms like Facebook Marketplace, where suppliers sell them for R10 to R20 a packet.

Migrant women living in Johannesburg say they use the birth control pills because they have no other local options.

They cite language barriers and the barring of undocumented foreign nationals from accessing services at public health centres by vigilante groups such as Operation Dudula.

Last year members of Operation Dudula and March and March carried out a campaign of

blocking undocumented foreign nationals from using public healthcare services in public hospitals and clinics, accusing them of draining resources meant for South Africans.

The South Gauteng High Court later issued an interdict against the acts.

Janet Moyo (not her real name), who supplies contraceptive pills in the Johannesburg central business district, says her clients resell them in informal settlements and to migrant communities.

Moyo says she bought the bulk stock from a police officer who confiscated a box full of contraceptive pills from smugglers.

“I don’t just sell these pills; I also use them to prevent unintended pregnancies. I have never used pills provided free in local clinics in South Africa,” she said.

“After I gave birth to my first child here in Johannesburg 12 years ago, nurses offered me local pills, a brand most women complain causes nausea, weight gain and mood swings. I took them but did not use them.”

Another supplier, Sizani Nkomazana from Yeoville, who gets her stock from Facebook Marketplace, would travel to Zimbabwe to get the pills, crossing the border with the help of amaguma-guma, men who smuggled goods and undocumented people illegally into South Africa for a fee. This carried the risk of being raped by the men and getting arrested.

“I would run out of stock and my clients would sometimes go without,” she said.

“The risk of buying in bulk poses a greater health risk of using pills that have expired or been stored under conditions that are not suitable for them.”

The smuggling network includes the suppliers of pills from clinics in Zimbabwe and transporters to the South African black market and has thrived despite concerted efforts, among them South African National Defence Force (SANDF) patrols along the border.

Challenges: Major Shihlangoma Mahlahlane of the Bravo Company of

the 10 AA Regiment Joint Technical Operation for Operation Corona.

Challenges: Major Shihlangoma Mahlahlane of the Bravo Company of

the 10 AA Regiment Joint Technical Operation for Operation Corona.

The pills are brought into the country by runners who use illegal routes and informal cross-border transporters called “omalayitsha” who transport goods and people without documents between Zimbabwe and South Africa, using amaguma–guma to get them across the border.

“It’s a challenge to stop smugglers coming into South Africa because there are a lot of exits within the fence and that is where the contrabands can cross over,” Major Shihlangoma Mahlahlane, of the Joint Technical Operation for Operation Corona, told journalists in 2024 at Ha-Tshirundu, a Limpopo village identified as a hotspot for smuggling goods between South Africa and Zimbabwe.

“When we patrol towards the east, then they cross towards the west because they know the area is vulnerable, it’s not covered .”

Operation Corona is an operation led by the SANDF at South Africa’s ports of entry to tackle border-related criminal activities.

Mahlahlane said contraband smugglers often bribed their way across the border, often at night or early in the morning, using the cover of darkness to avoid security forces deployed along the border line.

Migrant women also opt for smuggled contraceptive pills from Zimbabwe because of the advert effect local pills have on their bodies, supplier Moyo says.

“I have been using Secure pills from Zimbabwe for 12 years and never experienced any side effects. My skin glows and I haven’t gained any weight,” she said.

The pills are branded and distributed in Zimbabwe as Secure — a progesterone-only contraceptive, and Control — a combined oral contraceptive pills.

The pills are provided to hospitals and clinics through the National Pharmaceutical Company of Zimbabwe and sold at an affordable fee, while in private pharmacies they sell at US$1 for two packs.

“Zimbabwean migrant women’s beliefs and practices relating to contraception or antenatal care are a continuation from their country of origin.

Vigilance: A member of the South African National Defence Force on patrol duty at an illegal border activity

hotspot near the Beitbridge port of entry. Photos: Dianah Chiyangwa

Vigilance: A member of the South African National Defence Force on patrol duty at an illegal border activity

hotspot near the Beitbridge port of entry. Photos: Dianah Chiyangwa

These continuities are instituted and facilitated through a series of transnational activities, maintaining social ties and communication,” says independent researcher Sibonginkosi Dunjana.

In her research paper, “Exploration of Zimbabwean Migrant Women’s Beliefs and Practices Surrounding Access and Utilization of Contraceptives and Antenatal Services in South Africa”, Dunjana highlights that Zimbabwean women’s beliefs and practices surrounding contraceptives or antenatal care are complex, multilayered and characterised by multiple intersections between personal, social and structural factors from both the country of origin and destination.

Nobuhle Dube, a mother from Hillbrow, believes contraceptive pills from Zimbabwe are more effective than the ones provided at clinics in Johannesburg.

“One can get pregnant while consuming local pills; even some South African women prefer using pills from Zimbabwe,” said Dube, who used Secure while breastfeeding and now uses the Control pill.

“I buy the pills from black market suppliers for R20 per packet, and there is no need for regular check-ups like blood pressure while taking these pills.”

Socio-economic status, lack of documentation and policies also prevent migrants from using local health facilities and medication, studies say.

When Sihle Moyo, a Zimbabwean mother of one, gave birth to her child at the Hillbrow Health Clinic in 2017, she immediately started using contraceptive pills provided for free at the centre.

But she says that as the years went by, she started facing discrimination from nurses who told her that family planning pills were meant for South African women only. Dube was introduced to the black market by a relative.

According to the State of the World Population 2025 report titled “The Real Fertility Crisis: The Pursuit of Reproductive Agency in a Changing World”, not all health systems can provide the full range of sexual and reproductive health services, whether due to poor integration of these services within healthcare systems, provider bias, insufficient availability of affordable and quality reproductive health commodities.

Contraceptive listing: A screenshot from Facebook.

Contraceptive listing: A screenshot from Facebook.

It says health policies are some of the most impactful means of supporting and expanding reproductive choice and that better policies are needed to help prevent unintended pregnancies and for women to have children when they are ready for them.

Both needs can be addressed by ensuring that the full range of sexual and reproductive health services are available and well integrated into primary health systems.

Department of health spokesperson Foster Mohale said: “According to the law of the country, no one should be denied access to health care services due to nationality nor immigration status.”

The National Health Act stipulates that “everyone has the right to access healthcare services, including reproductive healthcare”

This applies to everyone who resides within the borders of South Africa, whether documented or not.

This work was produced through a grant provided by the Wits Centre for Journalism’s African Investigative Journalism Conference 2025.