Centralised leadership: Burkina Faso’s leader, Ibrahim Traoré, has gained popularity for asserting sovereignty,

tackling security challenges and rejecting ineffective foreign influence. Photo: Stanislav Krasilnikov/RIA Novosti

Over the past three decades, Africa has undergone significant political transformation.

After the end of the Cold War and the collapse of many one-party systems, the continent experienced constitutional reforms, multiparty elections, renewed commitments to democratic governance and efforts to move beyond colonial-era political and institutional constructs. Yet recent years have seen growing concern over democratic stagnation and erosion.

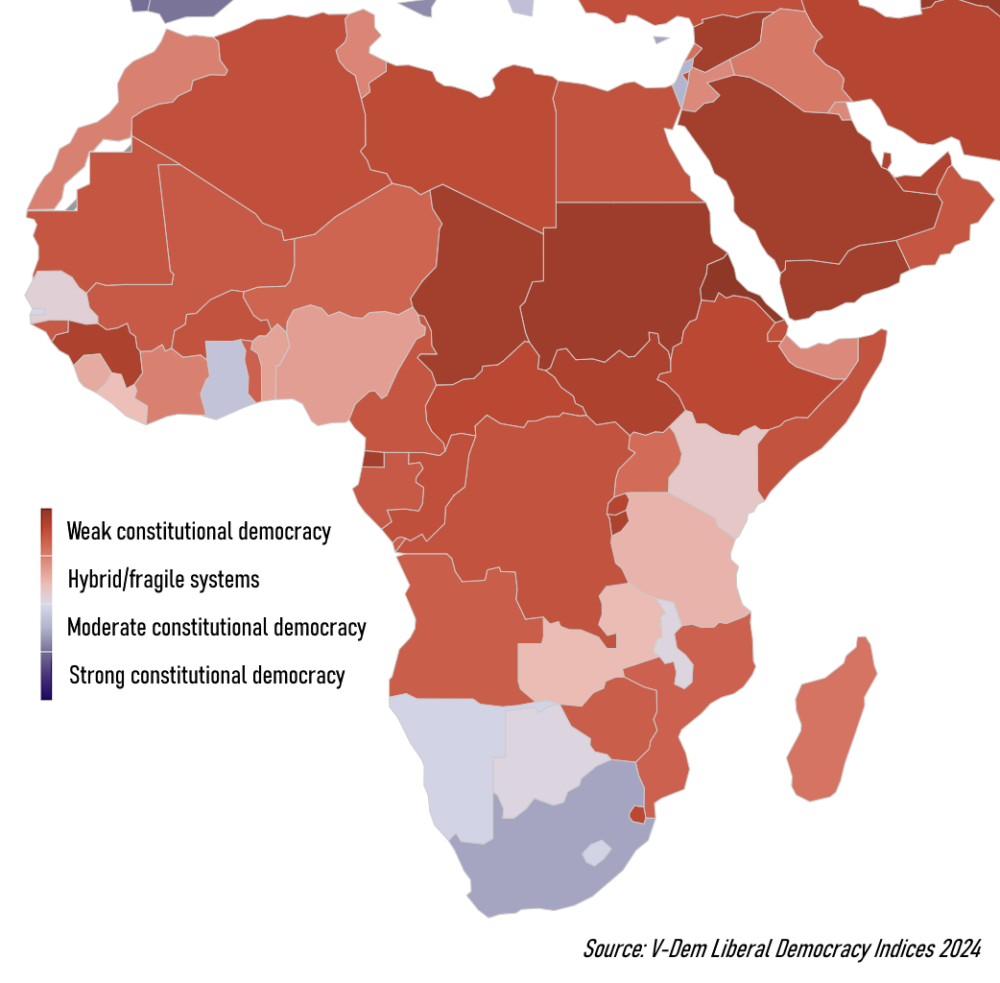

Using the V-Dem Liberal Democracy Index — which measures not only electoral competition but also institutional constraints on power, the rule of law, judicial independence and civil liberties — a clearer picture emerges of both progress and decline across Africa.

The 2024 snapshot shows that weak constitutional democracy remains the dominant condition across much of the continent. Large parts of North Africa, the Sahel, Central Africa and the Horn of Africa fall within the weakest category, reflecting limited institutional constraints on executive power and fragile rule of law.

A second tier of hybrid or fragile systems stretches across parts of West, East and Southern Africa, where competitive politics exists but institutional accountability remains uneven. Only a small cluster of countries, largely in Southern Africa, exhibit moderate to strong levels of constitutional democracy.

Overall, the map illustrates that while elections are widespread, the deeper foundations of liberal democracy — independent institutions, effective checks and balances and legal accountability — are weak or fragile in most African states.

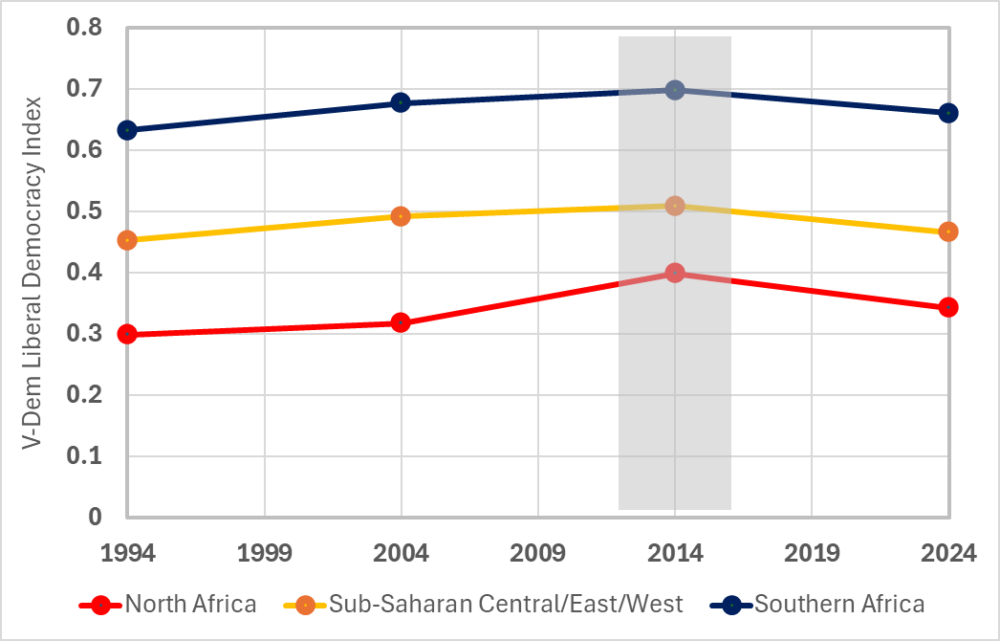

The V-Dem data also shows that liberal democracy across the continent improved steadily between 1994 and 2014. This period reflected the optimism of post-authoritarian transitions, constitutional reform processes and increased political openness. However, since the mid-2010s, the trend has reversed. By 2024, average levels of liberal democracy had fallen, signalling a broader pattern of institutional weakening rather than simply flawed elections.

Regional differences are striking. Southern Africa has consistently exhibited the strongest levels of constitutional democracy, while North Africa remains the weakest. Central, West and East Africa fall in between. Yet all three regions share a common trajectory: improvement in the first two decades after the 1990s, followed by decline over the past decade.

The pattern reflects a shift away from institutionalised checks on power towards more centralised and personalised governance systems.

The independence of courts has weakened in many countries, legislatures have struggled to constrain executives and ruling parties have increasingly dominated political space.

Levels of liberal democracy in Africa in 2024. Source: V-Demo Liberal Democracy Indices 2024

Levels of liberal democracy in Africa in 2024. Source: V-Demo Liberal Democracy Indices 2024

The decline is not primarily about the disappearance of elections — most African states continue to hold them — but about the erosion of the institutions that make democratic governance meaningful and accountable. The weakening of liberal democracy has often coincided with rising corruption, declining service delivery and reduced state capacity, as constitutional constraints give way to patronage networks and elite capture.

South Africa’s recent experience illustrates the dynamic. Despite regular competitive elections, the erosion of institutional independence through practices such as cadre deployment contributed to state capture, massive corruption and the deterioration of essential public services. This is precisely the kind of institutional decline captured by falling liberal democracy scores.

Yet the African experience also raises a deeper question: Is liberal democracy itself the ultimate determinant of governance quality, stability and economic progress?

History suggests that effective governance does not always emerge exclusively from liberal democratic systems. In certain contexts, strong, centralised leadership has produced stability and development — at least for periods.

Rwanda under Paul Kagame is frequently cited as an example of authoritarian or semi-authoritarian governance delivering impressive economic growth, improved infrastructure, reduced corruption and social stability. Political space remains tightly controlled, yet state capacity is high and development outcomes significant.

Similarly, Burkina Faso’s leader, Ibrahim Traoré, has gained popularity for asserting sovereignty, tackling security challenges and rejecting what many citizens perceive as ineffective foreign influence. Though far from democratic in the liberal constitutional sense, his leadership reflects widespread frustration with political systems that have delivered neither security nor prosperity.

Even Libya under Muammar Gaddafi, despite its authoritarian nature, achieved relatively high living standards by African standards, extensive social welfare programmes and national stability for decades — outcomes that collapsed after the removal of the regime in the name of democratisation.

The cases do not suggest that authoritarianism is preferable to democracy. Rather, they illustrate that governance capacity, institutional coherence and leadership quality often matter as much as — and sometimes more than — formal democratic structures.

The challenge in much of Africa is that the erosion of liberal democracy has not been replaced by disciplined developmental states or benevolent authoritarian systems. Instead, it has frequently produced weaker institutions, greater corruption and poorer governance outcomes.

The decline captured by the V-Dem indices largely reflects a move towards extractive political systems rather than effective alternatives.

This is why the recent democratic backsliding matters. Not because liberal democracy is a moral ideal in the abstract but because in Africa’s historical experience, weakening constitutional constraints have generally undermined state capacity.

Regional trends in liberal democracy in Africa, 1994–2024. Source: V-Demo Liberal Democracy Indices 2024

Regional trends in liberal democracy in Africa, 1994–2024. Source: V-Demo Liberal Democracy Indices 2024

Africa’s development challenges — widespread poverty, fragile economies and security crises — make procedural democracy insufficient on its own. Elections without effective institutions, competent administrations and accountable leadership do little to improve living conditions.

The continent faces a complex crossroads. A return to stronger constitutional governance could help rebuild institutions, limit corruption and improve accountability. Yet democratic renewal alone will not solve Africa’s challenges without efforts to strengthen state capacity and promote economic development.

Conversely, experiments with alternative governance models may continue to gain public support where democratic systems are seen to have failed. The risk, however, remains that without strong institutions and genuine accountability, such systems may reproduce new forms of elite capture and repression.

The trajectory of liberal democracy in Africa over the past 30 years thus tells a nuanced story. The early post-1990s period demonstrated that institutional reform and political openness could bring real democratic gains. The subsequent decade of decline highlights how fragile the gains remain.

Ultimately, the central lesson is not that democracy has failed Africa nor that authoritarianism offers a simple solution. Rather, governance quality depends on the strength of institutions, the accountability of leaders and the capacity of the state to serve its citizens. Liberal democracy has provided a framework for the conditions but without sustained institutional integrity it loses substance.

Africa’s future stability and prosperity will depend less on the formal label of its political systems and more on whether the systems — democratic or otherwise — can deliver effective governance, curb corruption and foster inclusive development.

Dr Joan Swart is a forensic psychologist and independent security analyst who writes on governance, sovereignty and geopolitical developments affecting Africa.