Even for those who don't understand the concept of radiation

The broken glass from a window pane cracks underfoot, a jarring noise amid the drone of mining equipment in the distance. It is one of the few reminders of a time when this upstairs room was the kitchen of the old Randfontein Club.

Faded photographs in the town museum show people sunbathing and swimming in the lake in the 1980s. There were bars, a jetty and a miniature putting course. Now only the foundations remain after it was closed because of the increasing concentration of uranium in Robinson Lake.

In the past it was a place for the residents of Randfontein – 50km west of Johannesburg – to relax on the weekend and forget their jobs in the mining industry. But in the late 1990s the underground mines started closing because the falling price of gold and uranium made them unprofitable. The mines were abandoned and the water levels inside started rising. Acid mine drainage began seeping into the dam, increasing the level of uranium to levels 220 times higher than the safe limit. The resort closed.

Deep into winter a chill breeze blows across the lake, creating ripples in the clear water. The surface is a stark blue reflection of the sky, with the bottom tainted red from the heavy metals in the water. No alga grow here, no fish swim, no underwater life ripples the surface.

The periphery of the lake is a wide ring of cracked yellow earth. The soil beyond is brown. There are 20m-high blue gum trees. There are yellow signs with “Radiation area – Supervised area” wired to the fence around the area and nailed to the trees.

Gold seam

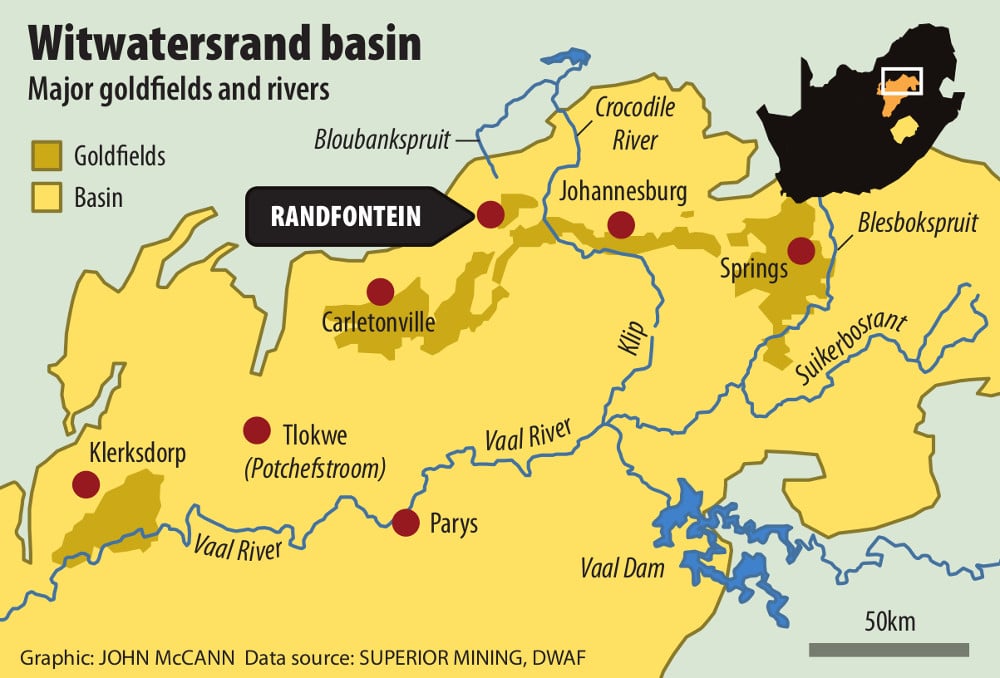

The Witwatersrand gold seam runs for about 100km, from Randfontein in the west of Johannesburg to Springs in the east. A century of mining drove a mining boom, thanks to this being the world’s largest concentration of the precious metal.

Mine shafts up to 3km deep were sunk. The waste was dumped above ground in over 400 mine dumps or tailings dams that now dot the province. These contain a mixture of heavy metals, and an estimated 600 000 tonnes of uranium.

The Cancer Association of South Africa (Cansa) says this is the only place in the world where large numbers of people live next to dumps full of uranium.

Yellow warning signs are wired to the fences around the area and nailed to the trees. (Photos: Madelene Cronjé, M&G)

It says up to 400 000 people in the Witwatersrand are exposed to low levels of radiation as a result, and tests Cansa did on the teeth of residents in Carletonville found uranium levels 100 times higher than normal levels. It says no research has been done in Gauteng about long-term exposure to mine dumps.

Managers of one of the Witwatersrand mines lived 300m from Robinson Lake. Their large red-brick homes were abandoned when operations ceased in the late 1990s, and have been occupied by squatters.

Abandoned mines

The tarred streets, laid out in a grid, are crumbling and overgrown. A worn football emits a hollow thump each time it is kicked by a handful of children playing in the street. Next to them five young men are sitting with their backs to a wall, trying to absorb some of the weak midday sun.

Two empty cartons of Chibuku sorghum beer have been discarded. There are three unopened ones in a plastic bag. A tall and athletic-looking Ronald Chauke opens one of these, and hands it round. “What does this radiation mean?” he asks, in response to my asking whether they are experiencing any health problems.

I recommend he goes to the clinic and ask for information there, but it is a R22 round trip by taxi to Krugersdorp and people here are lucky if they find work for three days in a week. With the mines gone the only work is as domestic workers.

The men stand at the main intersection coming into Randfontein, waiting to be picked up as day labourers. He does not look at me while I explain that kidney problems are almost guaranteed, and cancer, typically thyroid, is likely.

The National Nuclear Regulator has found uranium concentrations of 16mg a litre in Robinson Lake. Water affairs says a maximum concentration of 0.07mg is safe to drink. In 2002 it was declared a radioactive site thanks to the levels of uranium – one of 50 in the Witwatersrand. The regulator fences these off because people cannot be exposed to them for prolonged time. When people do live in dangerous places, it must move them. But the fences around Robinson Lake keep being stolen for scrap.

Radioactivity

South Africa has not done much of its own research, and relies in part on work carried out in eastern Germany, where uranium was mined during the Cold War. Here, old mines are fenced off and exclusion zones are established to ensure no one lives there. Naturally occurring uranium remains radioactive for billions of years, and these areas cannot be rehabilitated.

The National Nuclear Regulator had not responded to requests for comment by the time of going to print.

Ronald Chauke (far left) is one of the many people squatting in abandoned houses in the area.

Chauke does not drink or use the water from Robinson Lake for washing. He does not know what the radiation signs mean, but the lake scares him anyway.

“We know we cannot go near there. The lake is not normal.” Sitting back in his plastic chair he points at a mine dump 3km away. “That is our real problem. When the dust blows you cannot see the other side of the road. It covers everything.” He says it makes him and others cough.

“How can we know what is happening [inside our bodies] if we do not go to the doctor?”

‘How can you know?’

Pride Ngwenya has lived next to Robinson for 15 years, a few houses from Chauke. “We are told nothing so how can you know what is happening inside you?” Wearing a heavy black coat against the cold, he says “the [radiation] signs mean nothing if they do not tell you”.

“Obviously that lake and the mines are making us sick. But because nobody gives us the information on what is happening. You say it will make our children have problems, so what can we do because this is where we live?”

Uranium and other heavy metals are dispersed through water and wind. With Johannesburg being a watershed, rivers start here and flow east and west towards the Indian and Atlantic oceans.

Research by the nuclear regulator says radiation seeps into these rivers from tailings dams and is carried far downstream. The town of Potchefstroom is down-river from Randfontein, and is home to Professor Frank Winde’s laboratory. A lecturer in geography and environmental studies at North-West University, he says there are more than 600?000 tonnes of uranium sitting above the soil in Gauteng.

Uranium levels inside kettles he tested in the town were 20 times higher than levels in towns with water that was not affected by mining. The South African levels for uranium in water are four times the level recommended by the World Health Organisation (WHO), he says. Untreated water that he tested upstream had levels 4 000 times higher than this limit.

Isolated tests

Although isolated tests have been conducted, there has never been a comprehensive study of the air and water pollution from mine dumps.

The nuclear regulator has found uranium levels in Lancaster Dam outside Potchefstroom were 1.9mg a litre, and those at the nearby Hippo Pond were 2.1mg. A brickyard next to the dam uses the sand here to create building material. The WHO says 0.015mg a litre is the maximum.

Very little research has been done into airborne pollution – uranium in the dust is so fine that it can be blown far afield. A 2002 study by the government’s Council for Geoscience said: “Mining has resulted in the dispersal of radioactive material into the environment via windblown dust, waterborne sediment and the sorption and precipitation of radioactivity from water into sediment bodies.”

Former Witwatersrand mine managers abandoned their large red-brick homes when operations ceased in the late 1990s.

It also mentions the problem of no research on air pollution. “The lack of information has been identified as a serious information gap” and there was a need for a “comprehensive, credible monitoring programme”.

David Hamman, a researcher at North-West University, found traces of uranium in the kidneys of cattle living around the Wonderfonteinspruit.

Heavy metal vegetation

This river starts a few kilometres from where Chauke, in Randfontein, is sitting. Their kidneys had uranium levels 4 350 times higher than cattle living elsewhere. This was because of accumulation of heavy metals in the grass they were eating, thanks to dust and water, he found.

The South African Nuclear Energy Corporation released research in 2008 on vegetation around the Gerhard Minnebron wetlands near Potchefstroom. This found that levels of radioactive substances in plants such as oats and onions were three times higher than those considered safe for consumption. Speaking last year, former minerals minister Susan Shabangu said radiation levels were “not at a level that poses a threat to communities”.

In Krugersdorp, there is a community living on top of an old mine. The soil in the Tudor Shaft informal settlement was tested in 2010 by the Federation for a Sustainable Environment, an NGO, and found to have uranium levels of eight millisievert – the legal limit is one millisievert.

The residents and tailings dam were meant to be moved in 2010, but the federation opposed this, saying that disturbing the earth would throw uranium into the air. They requested that research be done before work went ahead. In their court application around the same time they cited the lack of research.

Where the technology was not there in the past to extract them, companies are now re-mining the dams, thanks to the higher prices of gold and other heavy metals. This will see the dumps disappear. High-pressure water blasts the dams apart, and the sludge is carried away by pipes to processing plants. At present, there is research into the effect of disturbing the heavy metals, and the toll on nearby communities.

Remediation costs

There are 6 000 abandoned mines in South Africa, and the auditor general said in 2009 that it will cost at least R30-billion to remediate these. The legislation around mines is based on the principle of “polluter pays” but until the 1980s mines did not have to bear the cost of remediating the areas they had operated in.

Now, the mines are fully responsible. But the mines, through the Chamber of Mines, argue that current companies cannot be held liable for the negligence of companies that have closed. Environmental groups have opposed this and said that when a company is transferred (all mines and their dumps are owned by someone) its assets and liabilities are carried through to the next owner.

The Gauteng part of this strategy – “Regional Mine Closure” – says the worst affected population when it comes to exposure to possible radiation are “informal settlement dwellers” living next to affected rivers.

These are people who are likely to be more at risk of illness thanks to their “poor nutritional status related to poverty and the prevalence of HIV and Aids”, it said.

What does uranium do?

When uranium is ingested it is deposited in the kidneys, lungs, brain and bone marrow. The alpha particles – which contain massive doses of energy – sit in these parts and damage the tissue around them. Because it is an endocrine disrupter, it increases the risk of fertility problems and reproductive cancer. Large doses are fatal, but the constant exposure to low levels has intergenerational effects that are still not fully understood.

Mining’s inevitable legacy

Robinson Lake is across a gravel road from the treatment works for the West Rand basin. When the underground mines in the area shut down, they stopped pumping water from their shafts. These filled up and the water mixed with heavy metals underground. In the late 2000s this water started spilling out of abandoned shafts and into local rivers and wetlands. The water affairs department said it needed a billion rand to build treatment works, which involved extending a plant already run by the mines. This is now operating and has stopped the decant into this basin.

The central and eastern basins – Gauteng has three major water basins – are filling up but those treatment works are also nearing operation. They will have to operate forever, with an annual cost estimated by water affairs of around R300-million, to ensure that untreated water does not seep into water sources.