Agriculture also faces a future in which the climate that it relies on is changing. More extremes, from floods to droughts, are already happening. (Sean Gallup/Getty)

COMMENT

With the aim of fighting unemployment, poverty and inequality, the promotion of co-operatives has been prominent in policy documents and pronouncements.

At an international co-operative conference in 2009, President Jacob Zuma summarised the rationale for the investment in co-operatives as follows: “Our call for broad-based economic empowerment highlights the co-operative form of ownership to benefit the whole community in a collective manner rather than developing an individual.” It was hoped that this would result in “decent work opportunities”, “sustainable livelihoods”, “increased agricultural production and productive land use” and “financially viable entities that can implement employment-intensive production schemes”.

The National Development Plan (NDP) notes that co-operatives have several benefits. For example, they help small producers, including rural development projects, achieve economies of scale and establish links to markets and value chains. They also promote economic transformation and economic empowerment by facilitating “ownership and management of enterprises and productive assets by communities, workers, co-operatives and other collective enterprises”.

Echoing the NDP, the government’s 2014-2019 medium-term strategic framework highlights co-operatives as part of “radical economic transformation” and says they will support excluded and vulnerable groups, such as small-scale producers.

A key initiative was the national informal business upliftment strategy, which was finalised by the department of trade and industry in 2014. It placed co-operatives along with small and medium enterprises as the target of policy interventions. It sees informal businesses “graduating” from just surviving to becoming informal traders, then informal micro-entrepreneurs and, finally, co-operatives or companies. This policy is now being implemented by the new department of small business development.

This article is based on findings of a 2014 study of co-operatives in the Free State to assess, inter alia, the success that has been achieved in promoting co-operatives. The research was funded by the International Labour Organisation at the request of the Free State’s department of economics, tourism and environmental affairs (Detea).

Co-operatives in South Africa are registered formal entities and not part of the informal sector. A co-operative enterprise is a generic form of business organisation, alongside sole proprietorship, partnership and incorporated forms.

The Co-operatives Act (14 of 2005) defines a co-operative as “an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic and social needs and aspirations through a jointly owned and democratically controlled enterprise organised and operated on co-operative principles”. It is unlawful to use the term co-operative, or co-op, for any entity not registered as such.

Since 2002, the government has devoted billions of rands to promoting co-operatives. Apart from a co-operative incentive grant of R350 000 per co-operative, funding is channelled to new co-operatives through the Small Enterprise Finance Agency, provincial development agencies, provincial departments of economic development, municipalities and the departments of agriculture, education, social welfare and others.

If one adds the large numbers of officials involved in the promotion of co-operatives — including provincial and municipal officials, Small Enterprise Development Agency staff and community-based workers — to the cost of co-operative summits and visits to co-operatives in countries such as Spain and Brazil, it is evident this initiative has been extremely well supported by the government.

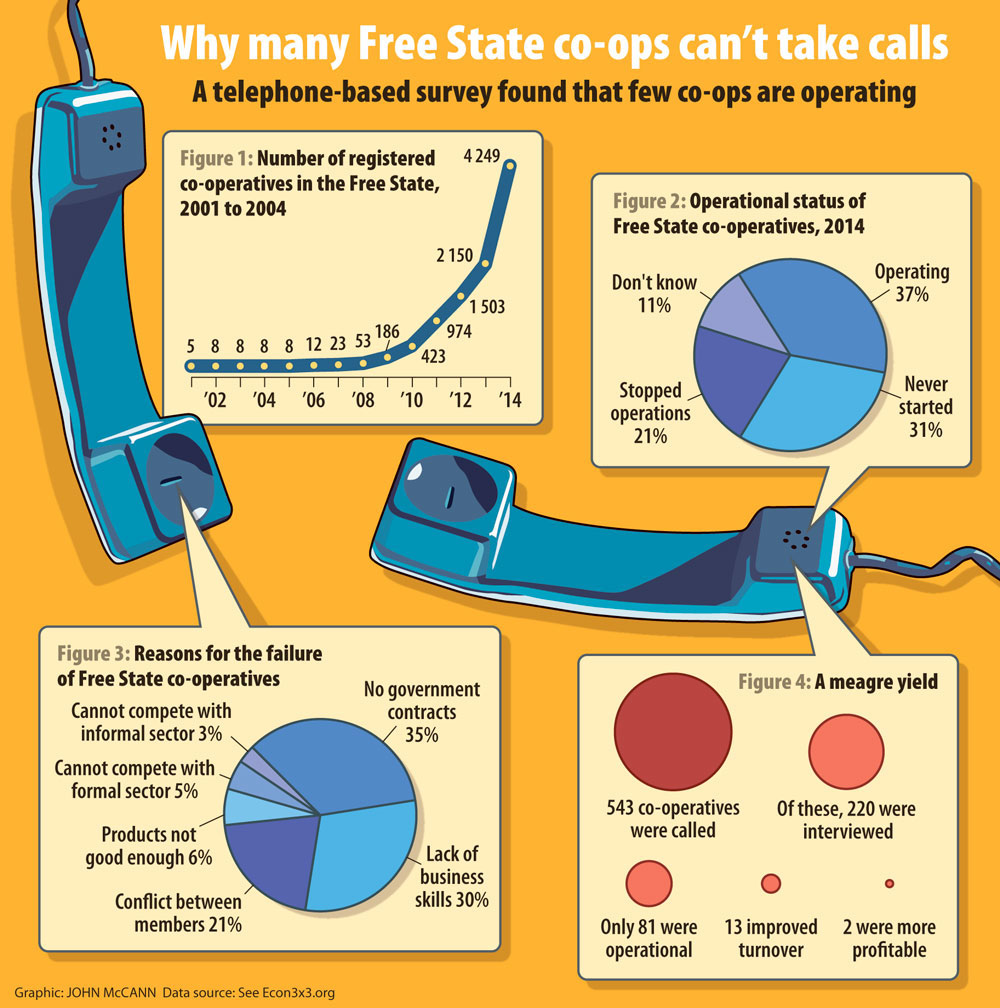

The number of registered co-operatives increased, thanks to this government investment, from 4 061 in 2007 to 22 619 in 2010 and 43 062 in 2013, according to data from the Companies and Intellectual Property Commission (CIPC).

However, in 2010, a study funded by the European Union found that only 2 644 of the 22 619 registered co-operatives were still functional — a mortality rate of 88%.

As stated in the report, the registration of a co-operative does not mean it is functional. Even in the CIPC register, a large percentage of co-operatives had only a physical address and no telephone number. Considering the importance of communication for enterprise operations, it is likely that co-operatives without phone numbers are inactive.

The research budget for the study only enabled phone interviews with 220 co-operatives and, later, in situ interviews with 42 co-operatives. The interviews were conducted with a member of the co-operative or, in the case of dysfunctional co-operatives, with a former member.

Of the 1 269 registered co-operatives in Thabo Mofutsanyana district municipality (in the Witsieshoek area), only 388 had listed phone numbers. Of these, in only 131 cases we reached an existing member of the co-operative or someone who had been a member at some stage.

Only 81 (37%) of the 220 co-operatives were considered still to be in operation, 21% no longer functioned and 31% never got going.

In the case of the 139 defunct co-operatives, the main reason given for the failure of a co-operative, or for it not having been started up successfully, was state contracts that had been promised (or expected) but did not materialise. A lack of business skills was a close second, followed by conflict between members of the co-operative.

Members of the co-operatives considered promises of government contracts for services (for example, office cleaning and the provision of food parcels for school-feeding schemes) as being crucial for success.

The co-operatives were state induced and did not constitute enterprises formed voluntarily — something considered internationally as a basic principle of a co-operative.

Of the 81 still operational co-operatives, asked whether the formalisation of their business activities into a co-operative had helped them to increase the turnover and profitability of their previous informal trading or service activities, only 13 indicated an increase in turnover and only two showed increased profitability.

The objective of creating employment opportunities has not been realised either. The 220 co-operatives jointly had 1 987 members when they were established but this declined to 1 562 members at the time of the interviews, although the majority of these no longer worked actively in the enterprise.

Of the 1 562 members, fewer than 16% worked in the co-operatives, but without regular remuneration. At best, part-time, mainly unpaid work emerged from this exercise.

The vast majority of co-operatives were created through government initiatives. For Detea officials, the establishment of new co-operatives was part of their performance appraisal (Detea 2014). There was more emphasis on officials achieving their performance targets than paying attention to basic entrepreneurial questions that should inform business creation.

Government officials promoting the establishment of co-operatives did not consider the business potential of local value chains. In the Metsimahole local municipality (in the Sasolburg area), for example, there was no evidence of co-operatives trying to tap into the petrochemical value chains.

Agriculture is a negligible contributor to both gross value added and employment, but almost 50% of the 693 co-operatives in the Metsimahole district were established to pursue farming activities, 106 of which targeted poultry production.

Lastly, little consideration was given to entrepreneurial opportunities. Analyses by the Enterprise Observatory of South Africa of formal enterprises in 280 cities and towns show little, if any, available entrepreneurial opportunities for businesses that sell undifferentiated products and services, which is what most co-operatives try to do.

In 2010, in her presentation to the parliamentary select committee on trade and international relations, the then deputy minister of trade and industry, Maria Ntuli, acknow-ledged the high failure rate and said only 132 of the 22 030 co-operatives had submitted financial statements to the Companies and Intellectual Property Registration Office (Cipro, now the CIPC).

She said that “officials at all tiers of government have a limited understanding of co-operatives as a form of business” and there was “inadequate institutional capacity to deliver on co-operatives”.

Despite this, the government continues to promote co-operatives as an important strategy to overcome unemployment. The department of trade and industry’s 2012–2022 integrated strategy on the development and promotion of co-operatives and the 2014-2019 medium-term strategic framework basically promises more of the same, so it is time for a comprehensive review of this. The evidence to date indicates that it is a very costly programme that fails not only the policy objectives but also the poor, whose hopes are ignited by the promoters of co-operatives.

Johannes Wessels is the director of the Enterprise Observatory of South Africa. This article was first published on the Econo3x3 website