Photo: Arnot Power Station

Bianca Goodson has released a detailed statement and 65 annexures, charging that her former firm, Trillian Management Consulting, facilitated access to decision makers for consulting multinationals McKinsey and Oliver Wyman. In return for this political capital, she states, Trillian was to get up to half the fees in lucrative consulting contracts with state entities.

Goodson initially started preparing her statement for the expected parliamentary inquiry into state capture, but after repeated delays decided to make it public via the Platform for the Protection of Whistleblowers in Africa (Pplaaf).

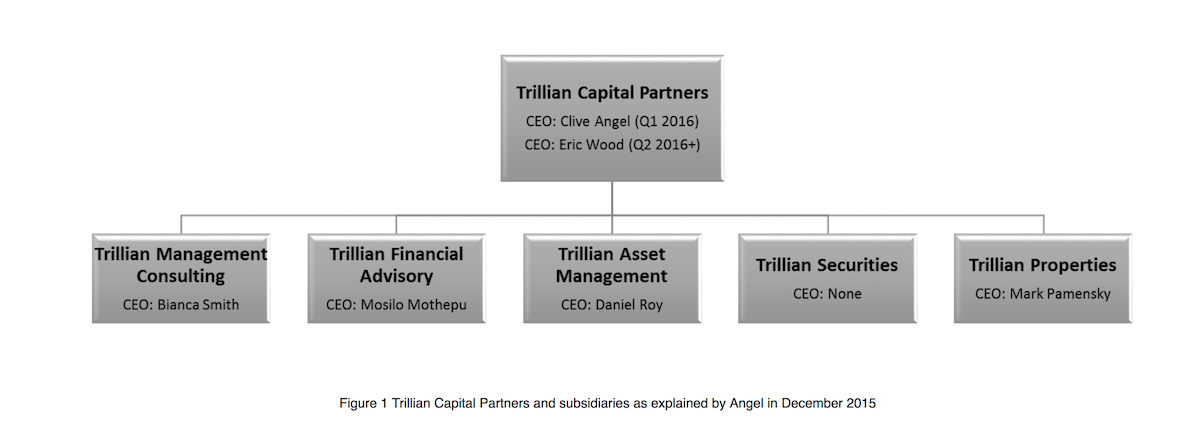

It is telling that Bianca Goodson’s whistleblower statement starts with the title, “My introduction to; and exit from Trillian”. The former Anglo American manager spent just five months working for the controversial consulting firm.

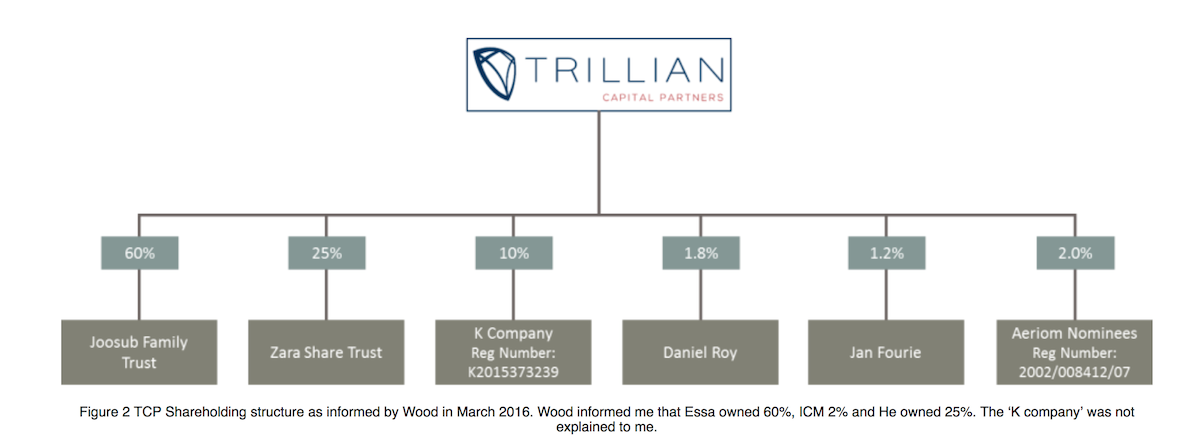

On 19 March last year she resigned as the chief executive of Trillian Management Consulting, the consulting subsidiary of Trillian Capital Partners, then controlled by Gupta lieutenant Salim Essa.

“The risks associated with this position, and specifically … with the shareholders of this company, are exceptionally high. Succinctly put – my career would be over if there was ever a public association between myself… Guptas and/or Salim,” her 6am resignation letter read.

“Although not much, my humble career history has been established on bloody hard work and integrity. I would rather have a future career defined by those attributes than a politically connected one.”

Since then she has sat on a goldmine of information about Trillian, its special relationship with “captured” officials, and the on-off partnership with consulting giant McKinsey that landed Trillian hundreds of millions from Eskom.

“I wanted to speak up sooner, but I was scared… I was 100% out of my depth in terms of the company that I briefly kept,” Goodson told amaBhungane this week.

“When [former Public Protector Thuli Madonsela’s] team approached me for a statement towards their state of capture report, I was excited because I felt that I finally had the opportunity to do the right thing.

“Alas, her report appears to not have been effective in stopping the likes of Trillian… [The parliamentary inquiry] came up as an option and straight away I started preparing… I’ve been waiting for Parliament since [but] I don’t believe that I will be called and I feel that I’m not doing the right thing by just waiting and keeping quiet.

“So now, I’m doing the right thing, regardless of risk.”

The gatekeeper

Goodson’s disclosures add to the growing body of evidence that suggests that, starting in December 2015, Trillian became the gatekeeper of lucrative consulting contracts at some state entities.

If international consulting firms wanted in, they would have to take Trillian as their “supplier development” partner and give it anywhere up to half of the contract.

“TMC’s [Trillian Management Consulting’s] business model was that work is secured through [Salim] Essa’s relationships and TMC benefits from these relationships through ‘supplier development’ agreements,” Goodson says in her statement.

“As such, TMC did not directly conduct any work with government departments or state-owned entities like Eskom, Transnet or Cogta [the Department of Co-operative Governance and Traditional Affairs]. Rather, [Trillian] secured work and thereafter passed the work over to internationally recognised companies and acted as the supplier development partner of choice, with roughly a 50% share of revenues.”

This was a symbiotic relationship.

The Trillian group was set up in 2015, and although it planned to bring experienced staff on board, the company itself had no track record. As such, TMC needed reputable international companies to act as an icebreaker, bringing Trillian in in their wake.

Trillian denied most of Goodson’s allegations and responded in writing, saying: “Trillian has never held itself out to be a gatekeeper of any institutions and is of the firm view that the skills base of its employees and its history of delivery was sufficient to procure work…

“Trillian consisted of approximately 80 highly skilled consultants and financial services professionals… Trillian has always followed due process in securing work either directly or in partnership with others. Trillian did not have any advantage over any of its competitors and Trillian had to compete on its offering.”

Yet, for a new company, Trillian’s bounty was extraordinary. Soon, it raked in R595-million from Eskom by acting as McKinsey’s de facto supplier development partner. McKinsey itself controversially received just over R1-billion from the same engagement despite it being terminated after just six months’ work, in July 2016.

The cancellation came some time after McKinsey told Eskom it could not partner Trillian because of “concerns about its ownership”.

“I questioned [Trillian representatives] on the prosperous windfall that [Trillian] appeared to have secured,” Goodson says in her statement. “I was told that [Trillian] is fortunate to have relationships with the people that ‘open the taps’ and that ‘South Africa’s wealth should not be only with the Ruperts and Koseffs of the world.’”

Trillian said it is unaware of a statement like this being made, but says if so would be “inconsistent with the ethos of Trillian”.

McKinsey has not given details of how it originally decided on Trillian as partner other than to suggest it had inherited it from Regiments Capital, an earlier partner where some Trillian staff had worked.

It has insisted that its fees from Eskom were “in line with similar projects we, and other firms, undertake in South Africa and elsewhere around the world. We … stand fully behind the impact and value we delivered.”

The people that open the taps

The Eskom deal – a “turnaround” consulting project – was secured in December 2015 when McKinsey agreed to partner Trillian in principle. As previously reported, the deal bypassed an open tender and Treasury rules.

The contract was projected to earn McKinsey R3.6-billion and Trillian several billion more over three years. But from day one there were problems as McKinsey consultants pushed back against the Trillian team’s presence.

In a 14-page report from January 2016, Goodson details how McKinsey treated Trillian as an “unwanted piece of baggage”, at one point telling it that “[supplier development] doesn’t really matter as long as you get your percentage”.

“I did not at that time understand the resistance on the part of the McKinsey & Co to include TMC in decision-making,” Goodson says in her statement.

Trillian replied: “Any insinuation that Trillian was a passive supplier development partner … to international companies is incorrect and Trillian would at all times have completed its share of the allocated work.”

At this point Trillian still had no formal contract with either Eskom or McKinsey. Despite this, Goodson says, Eskom’s doors opened.

“Essa would arrange meetings between myself and Eskom’s [group executive for generation] Koko Matshela to discuss the barriers TMC and [Trillian subcontractor] eGateway were experiencing with Eskom… Essa consistently gave me assurance that if I encountered any resistance in doing my work, he would remove it.”

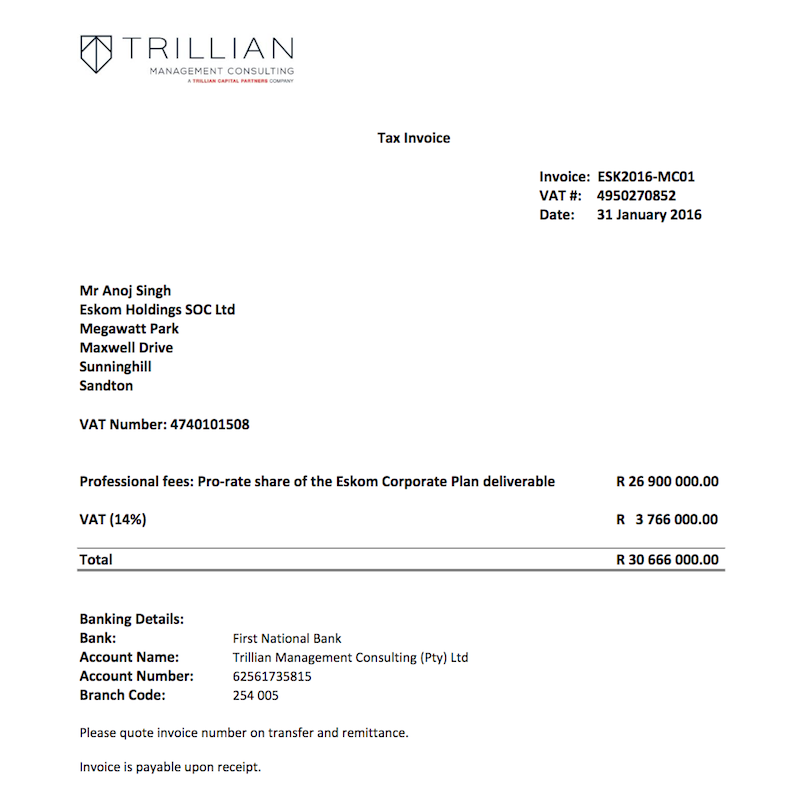

On 3 February 2016, Trillian approached Eskom chief financial officer Anoj Singh with a bold request: even though McKinsey and Trillian still had not signed a formal agreement, it wanted the go-ahead to invoice Eskom directly.

“A company of Trillian’s early stage and developmental nature is reliant on cash flow to grow and any unnecessary delays in receiving payment for work done and resources committed will negatively impact the business’ ability to operate effectively,” Trillian wrote.

“In anticipation of [Singh’s] favourable response”, Trillian attached an invoice for R30.7-million for its 30 percent share of the Eskom corporate plan, a smaller contract that McKinsey had been awarded in September 2015 already.

The letter bears Goodson’s signature, but she denies writing it and says an image of her signature “was used on invoices and formal letters without my consent”.

A statement from a former Trillian executive supports Goodson’s claim that she did not write the letter.

Trillian denies that any executive’s signature was used without their knowledge or consent.

How Trillian, a company that was still in the early stages of being established, managed to carry out R30.7-million worth of work by the end of January remains a question.

A spreadsheet from Trillian and McKinsey’s initial meetings in December 2015 shows that McKinsey promised Trillian a 30 percent cut of the project.

“Between 1 January and 29 February 2016, TMC comprised of just two employees – one COO and myself,” Goodson says in her statement.

Goodson also disputes that any meaningful work could have been carried out by the time Trillian submitted the invoice. “TMC did not have employees to conduct the work; [and] my COO and I did not conduct any billable work during the 1st quarter of 2016.”

Trillian declined to provide a breakdown of billable hours performed on this Eskom smaller project, but did say that “it has only invoiced client for work actually done”.

Records show that Eskom paid the R30.7-million invoice.

Trillian also appears to have received a helping hand from Eskom’s head of procurement, Edwin Mabelane, who emailed Goodson copies of McKinsey and Eskom’s draft service level agreement, marked confidential.

Despite Trillian not being a party to this contract, Goodson says Mabelane “afforded me the opportunity to recommend changes to the [skills development and localisation] annexures of the contract”.

Trillian’s proposed changes, which would force McKinsey to include Trillian in all aspects of the project, were sent back to Mabelane a few days later.

Questions about these meetings and engagements were put to Eskom and the executives concerned. Eskom said it could not comment pending “an ongoing investigation and other internal processes previously announced”.

The Dubai consultants

However, McKinsey was not the only big fish Trillian was targeting.

In January 2016, two senior partners from international consulting firm Oliver Wyman arrived in Johannesburg, after being introduced to Essa in Dubai.

“[Trillian group CEO Eric] Wood explained that Essa had arranged for Oliver Wyman to be the preferred consultants to work at Cogta and Transnet,” Goodson says in her statement.

Des van Rooyen had recently been appointed as the minister of Cogta – the department of co-operative governance and traditional affairs – after a brief stint as finance minister.

The #GuptaLeaks also show that he had just returned from a short stay in Dubai, seemingly paid for by the Guptas.

A Cogta spokesperson commented: “[The] minister’s trip was paid for by himself and he did not meet or discuss work at Cogta with Guptas, their representatives or Mr Essa.”

For Trillian, Oliver Wyman’s visit to South Africa appears to have been an opportunity to show just how connected they were.

Over a two-day period, Trillian arranged a dinner with Transnet chief financial officer Garry Pita and meetings with Eskom’s Singh and Van Rooyen for Oliver Wyman executives Bernhard Haartmann and Maarten De Wit.

Goodson says she was asked to prepare a profile of Trillian that could be presented to Van Rooyen at the meeting.

“I was instructed to present capabilities for an organisation that had no prior history and for work not yet identified as a need. Regardless, the Minister appeared satisfied with our presentation… The [Oliver Wyman] directors were most impressed at TMC’s ability to secure work.”

The Cogta spokesperson confirmed that the meeting took place but said: “Minister van Rooyen has engaged with various stakeholders across the local government sector, as is his responsibility and as do all ministers in the line of duty… These interactions are in no way indicative of any translation into procurement.”

Trillian and Transnet also confirmed that these meetings took place, but deny that Trillian had special access.

“Trillian like any other consulting firm would arrange regular meetings with and discussions with clients and potential clients as part of its business development activities. This is an industry-wide practice and Trillian is no different in this regard. It is denied, however, that Trillian used these meetings as an opportunity to gain any unfair advantage,” Trillian said in a statement.

A Transnet spokesperson said the dinner with Pita was “normal business practice”, adding: “Transnet has met with representatives from Oliver Wyman where the consultancy presented its profile and skills set.

Similarly, Transnet has provided an update on the company’s plans, including procurement processes. [But] no proposals were presented.”

Back in Dubai, De Wit sent a memo outlining Oliver Wyman’s two-year plan for Cogta.

“This would be a very large project as we’re talking here developing plans for each and every Municipality (except probably the large cities, ie. around 266 Municipalities). We’re not sure if the Minister would be ready to buy such a large engagement,” De Wit’s memo reads.

But gauging the minister’s willingness is easier to do when you have help from the inside.

Bobat and the state capture play

It is worth going back to 9 December 2015 when President Jacob Zuma fired Nhlanhla Nene as finance minister.

Another Trillian whistleblower provided a statement to then public protector Thuli Madonsela in 2016, alleging that Trillian sought to capitalise on Nene’s firing, and that Mohammed Bobat, an associate of Trillian group chief executive Wood, would be placed at the Treasury to channel tenders to Trillian.

As has been widely reported, when Van Rooyen arrived at Treasury, Bobat was in tow.

When the minister was redeployed to Cogta, Bobat went with him.

If there was a plan to capture Treasury as alleged it did not work, but with Bobat now at Cogta the department appears to have become a new focus for Trillian.

“Although Bobat was employed at Cogta during my tenure at [Trillian], he was still highly influential to the operations of [Trillian],” Goodson says in her statement.

Bobat denied this, saying: “I have never worked for Trillian… Any insinuation that I was involved in their day to day operations is mere conjecture.”

Goodson says she was “informed … that [Trillian] would be working with Bobat at [initially] Treasury and later, Cogta, taking over … contracts at Transnet and hopefully other work in [state-owned entities].”

Goodson also says that Bobat soon started offering his assistance on the Oliver Wyman-Trillian proposal.

“The unsolicited proposal prepared for Cogta was informed by information that Bobat sent to me…

“In addition to this, I would receive timeline expectations and available budget information from Bobat, to ensure that the proposal was received favourably.”

Bobat confirmed that he met with Oliver Wyman and offered some initial comments on their proposal but denied “sharing any budget information or information which was not publicly available… I desisted from making any further comments or seeing any further proposals past the first draft, once I had realised that the scope proposed was beyond what was required.”

Oliver Wyman said in response to questions that Trillian was “identified … as a possible BEE partner” but that following an assessment of Trillian and their possible clients, it decided to back away from any engagement because of “governance” concerns.

“Not one of the opportunities that were explored with [Trillian] passed all [Oliver Wyman’s] governance tests. [Oliver Wyman’s] governance processes accordingly led to the rejection of any contracts/partnerships that were explored with [Trillian].

“All the interactions between [Oliver Wyman] and [Trillian] were exploratory in nature and did not result in any fee being paid to [Oliver Wyman] or [Trillian].”

The final straw

On 18 March 2016, Goodson was asked to sign documents opening a new bank account with the Bank of Baroda. When she questioned why Trillian needed another bank account when it had one with Absa, she was told this one was to “facilitate work with eGateway”.

EGateway is an Indian company that was subcontracted by Trillian to provide technical skills on the Eskom turnaround programme.

It was anticipated that more than 77 percent of all revenue Trillian received on the generation part of the Eskom project would flow to their postbox office in Dubai, although Trillian said that ultimately no payments were made to eGateway.

Goodson resigned the next morning.

Goodson claims that Trillian saw its time to make hay as being limited to what appears to be Zuma’s time in office, saying she was told on numerous occasions that, “The relationships that [Trillian] had were limited by and intended to operate for the duration of ‘the current dispensation’ only. As such, all work was forecast for the period 2016 – 2019.”

Trillian denies this, saying it was “established as a long-term business and was fully staffed and capitalised for that purpose.”

Trillian also implied that as a result of the negative publicity it has received the firm is now in a precarious position.

Goodson is going public at great personal risk. Trillian has laid a criminal complaint with the police against Goodson’s former colleague, the first Trillian whistleblower.

Regarding that case, Trillian told amaBhungane: “Trillian is entitled to enforce its [legal] rights, it cannot understand why it is being vilified for doing so.”

Goodson says seeing the pushback faced by her former colleague initially made her hesitant to speak out. “It broke my heart to see what she was going through and it wasn’t even her fault – she didn’t commit fraud nor did she extort any [state-owned entities], yet her life was ruined. So I wanted to do the right thing, but was scared.”

Now, however, Goodson says she is willing to take the risk. “The people responsible for state capture must be held to account for their actions, instead of people like [my former colleague] being targeted in the process.

“I hope that the risk that I am taking supports the objective to stop the looting and having innocent people take the fall for it.”

- This story was amended after publication to insert comment from McKinsey.

The amaBhungane Centre for Investigative Journalism produced this story. Like it? Be an amaB supporter and help us do more. Know more? Send us a tip-off.