BEE has also been a source of fierce contestation within the party. (Skyler Reid/M&G)

The Constitution requires that political parties must disclose their funding, the high court in Cape Town ruled on Wednesday. If this is confirmed by the Constitutional Court, Parliament will have 18 months to make that happen.

As the law stands, political parties can receive money from foreign donors, and even big sums of cash, and the public will never know about it, Judge Yasmin Shehnaz Meer said in her judgment.

“The receipt of such funding and the identity of the donors would arguably have a significant bearing on a party’s foreign and domestic attitude,” said Meer, agreeing with the civil society organisation My Vote Counts, which had challenged party funding secrecy.

She also agreed with a previous minority judgment in the Constitutional Court, which described private donations to political parties as ultimately public in nature in light of the reason why parties receive taxpayer funds.

“Political parties receive public resources because they are the vehicles for facilitating and entrenching democracy,” Meer quoted from a September 2015 Constitutional Court judgment. “This entails a corollary: that the private funds they receive necessarily also have a distinctly public purpose, the enhancement and entrenchment of democracy, as well as a public effect on whether democracy is indeed enhanced and entrenched. The flow of funds to political parties, public or private, is inextricably tied to their pivotal role in our country’s democratic functioning.”

The high court case was a sequel to that Constitutional Court case, in which a majority of judges said My Vote Counts had to challenge the Promotion of Access to Information Act in the high court if it wanted parties to name their donors.

When My Vote Counts did so, the Democratic Alliance, the only political party to oppose the application, vociferously argued that donors to political parties were entitled to privacy, and that donors to minority parties required privacy to shield them from a vengeful ruling party.

The DA had also said My Vote Counts should have provided evidence that party funding secrecy impoverished voter rights, and held that corruption can be fought with anti-corruption laws rather than with party funding reform.

These arguments were also dismissed, with costs awarded against the DA and the minister of justice, who had sought to defend the constitutionality of the Act.

Using the Act to demand donor information from political parties had proven impractical, and provided many loopholes, Meer said. Parties could fight such requests or could hide behind a confidentiality agreement with donors. They could even simply not record details of donations, or destroy such records before they are requested.

But Meer stopped short of ordering that donor information had to be systematically recorded and regularly disclosed, saying that to make such an order would be too close to telling Parliament what it should do.

For more than a decade, Parliament and major political parties have resisted all attempts to force a disclosure of their donors — or even statistics that would show how much of their funding was derived from foreign sources.

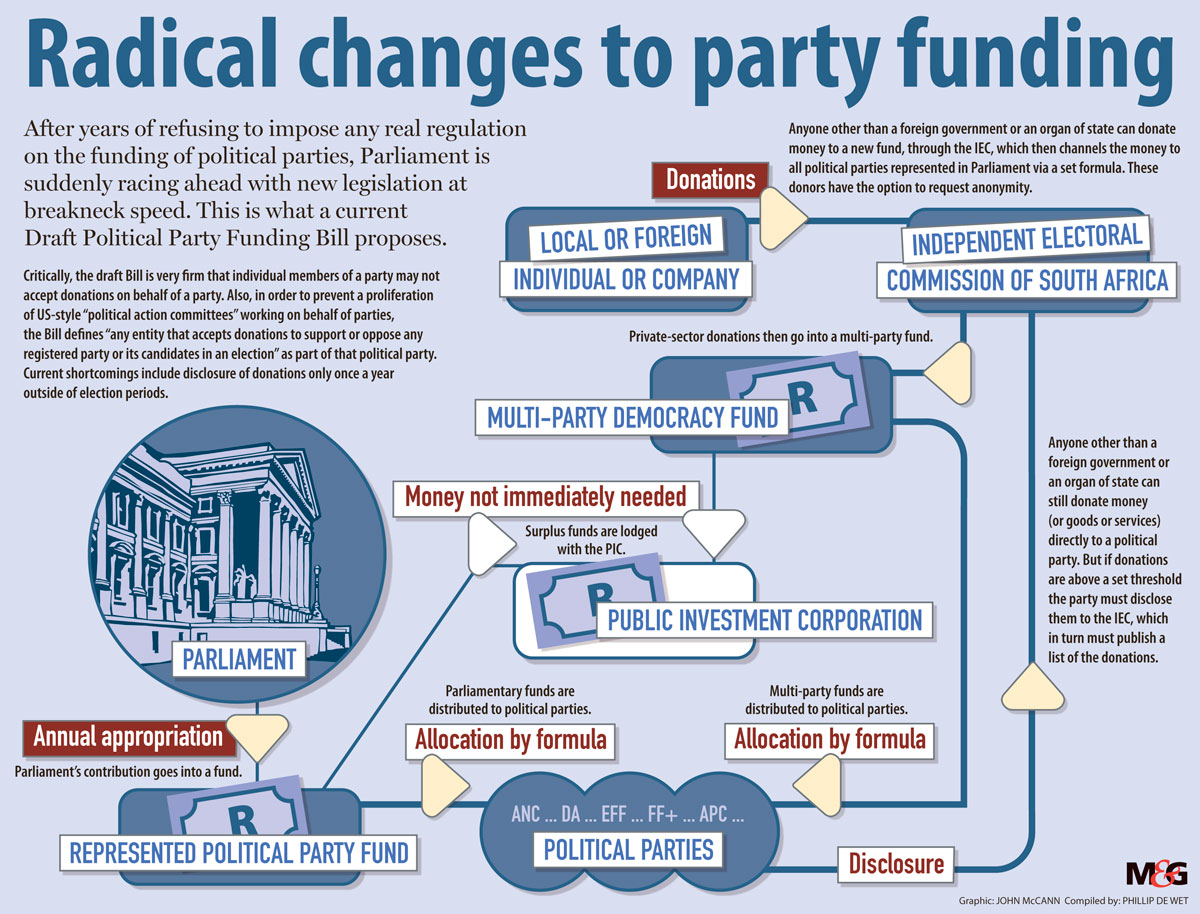

But, shortly before the My Vote Counts challenge was heard, a committee sprang into action and last week published the first draft of a Bill on party funding (see graphic above).

In terms of it, political parties would be obliged to record donations systematically, even donations in kind, and the Independent Electoral Commission (IEC) would be required to publish those details regularly.

Parties that failed to record or disclose donor details to the IEC would face fines of up to R1-million for a fourth offence in a three-year period. The same fine would apply to anyone who made a donation to a party member, or the party member who accepted it, for party political purposes.

The draft Bill does make provision for anonymous donations, but only to a multiparty fund, which would distribute the money to all parties represented in Parliament according to a formula based on how many votes they attracted.

Meer referred her judgment to the Constitutional Court for confirmation.

The draft party funding Bill is open for public comment until October 16.