Gangs are a daily reality in many Cape Town suburbs

At the height of apartheid, with Security Branch officers terrorising people in townships across the country, residents of Bishop Lavis in Cape Town started their own organisation to deliver much-needed services and to campaign against the regime’s oppression.

With street committees on every block and weekly meetings in community halls to report back on the fight against apartheid, the 1980s Bishop Lavis Action Committee (Blac) found popular support among residents.

Now, more than 20 years later, Blac has been restarted by some of the same activists who were involved back then, who say the provincial government is not responding to their troubles. Faced with a struggle against drugs, gangsterism and poverty, Blac is trying to restore some normality to the area.

“Ons loop nie meer met geld in die aand nie. Hulle wag jou in om jou te rob [We don’t walk with money at night any more. The gangs lie in wait to rob you],” Bishop Lavis resident and Blac member Arelene Barends told the Mail & Guardian.

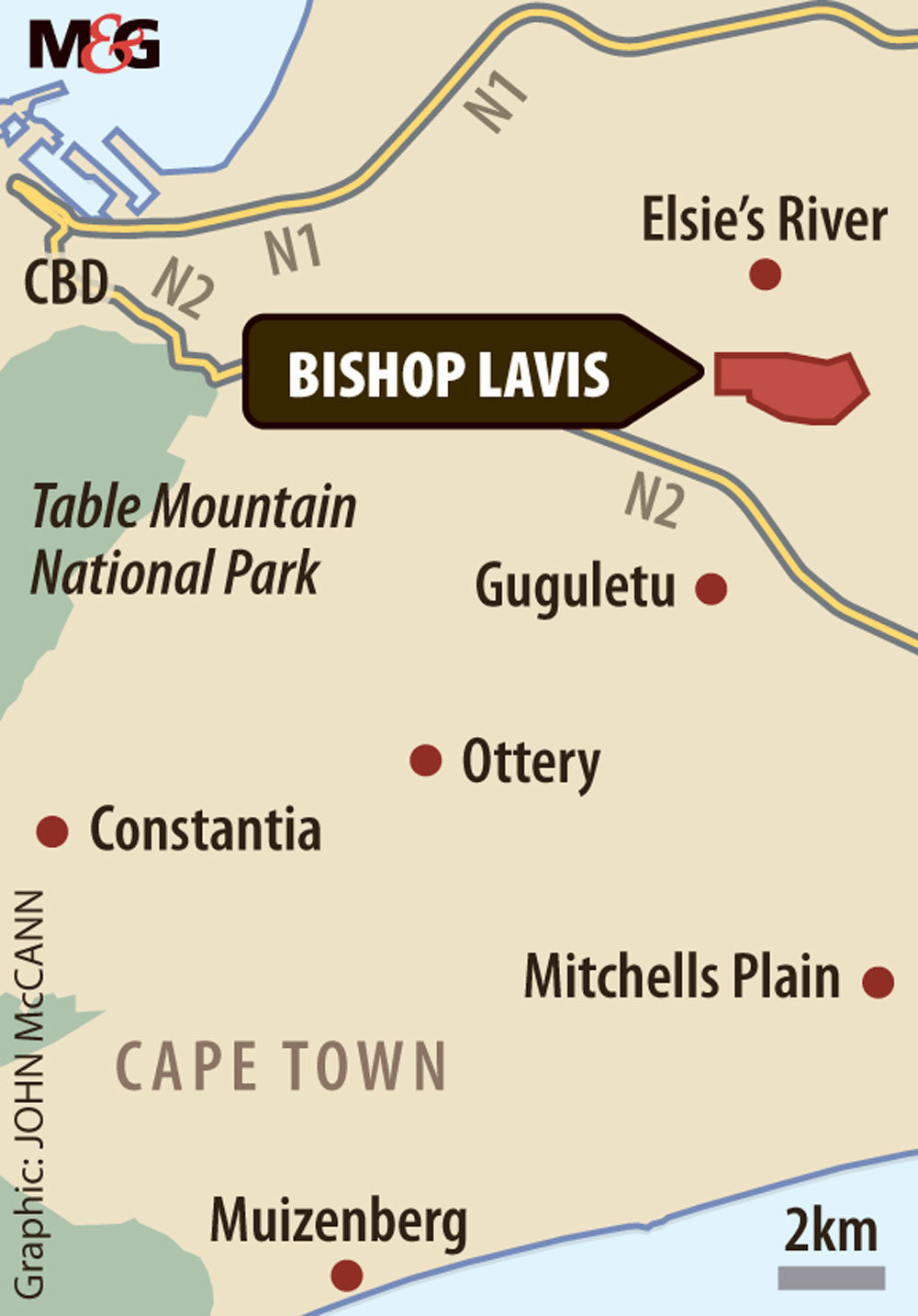

Ward 24, where Blac operates, is home to about 35 000 people and is only a small part of the entire Bishop Lavis area. The 2011 census estimated the unemployment rate in the area at 60%, and only 26% of the residents hold a matric certificate. In the 2016 elections, the Democratic Alliance won control of the ward with 73% of the vote, and the ANC secured 13%.

Last week, residents of Bishop Lavis said that gangs dominate daily life in the suburb by, for example, charging taxi associations protection fees and making areas inaccessible to residents.

“It’s really unfair because, for someone like myself, I don’t have transport so I have to use taxis. There’s always this fear that something will happen,” Barends said.

Blac president Victor Altensteadt said: “We are trying to restore some normalcy in the community, and get programmes running that will benefit the unemployed and people that are struggling here. We’ve collected the names of unemployed people and made a database for the department of labour, and we’re also trying to keep the kids away from gangs with our daycare programmes.”

[The Bishop Lavis Action Committee, headed by Victor Alensteadt, has met various organisations to co-ordinate plans to limit gang activities. (David Harrison)]

Bergville Primary School principal Aleem Abrahams was a founding member of the 1980s-era Blac and believes there is now an even greater need for the organisation.

“Now, more than ever, there is a need to get Blac restarted. Gangsterism is still rife in the community and, when we launched it in the 1980s, we realised that Blac had the potential to make a big impact. That same potential is here now,” Abrahams said.

In June last year, at least 17 people were shot dead in Bishop Lavis in violence between rival factions of the 28s numbers gang. The gangsters shot at each other across a busy street next to blocks of flats.

That spate of shootings led to the rejuvenation of Blac. A week after the killings, a few residents co-ordinated a wreath-laying ceremony at four of the sites where people had been killed. On the day of the event, thousands of residents pitched up to support the cause.

“It all started on a WhatsApp group,” said Blac deputy president Beverly Fortuin. “We were just here trying to organise an event to lay the wreaths at the gravesites to say: ‘Enough is enough.’ But as we were marching through the community, more people joined in. Soon there were thousands.”

The organisation is dominated by women, who run most of the projects and mobilise residents for big events. Four months after its inception, Blac held its first meeting with religious organisations, school principals, the community policing forum (CPF) and the police.

The Bishop Lavis police station commander has endorsed the group and said that, since its re-emergence, the number of gang-related shootings and killings had fallen.

Pastor Wesley Moodley, the chairperson of an interfaith organisation in Bishop Lavis, confirmed this. He said the different organisations had attempted to join hands to initiate programmes but had met with resistance from the ward committee.

There are about 10 people on the Blac executive committee and they co-ordinate programmes out of a container on the local sports field. The organisation offers literacy classes for children, counselling at all the schools in the area, programmes for elderly people and free legal advice on Wednesdays.

“In the counselling [sessions], gangsterism dominates the concerns of the kids,” Fortuin said. She also works as a counsellor at the schools.

Blac members are also volunteers for the “walking bus” initiative: adults walk alongside pupils to school in the mornings to prevent them being attacked by gangsters or getting caught in the crossfire. The “walking bus” started in Manenberg in 2016 and has spread to Hanover Park and Bishop Lavis.

Western Cape Premier Helen Zille has described the gangs operating in the city as a law unto themselves, and claims they prevent the government from doing its work.

“The gangs even try to take over walking buses, to control them. They say to some of our service providers: ‘Unless you pay us protection money, you can’t provide a service here.’ Trains can’t run any more. They have set up a parallel, lawless, violent authority,” Zille said.

Blac receives no funding and depends on the goodwill of residents, doctors, lawyers and volunteers. Six months after it was founded, the organisation is seen as an adversary to the local ward committee, led by DA councillor Asa Abrahams.

“Asa doesn’t come here any more. We tried everything to get in contact with her but she says Blac is an opposition party,” resident Magdalene Koopman said.

Abrahams did not respond to repeated requests for comment but the city’s mayoral committee member for safety and security, JP Smith, said: “Often these community organisations are heavily laden with politics and aspirant politicians, and there’s elections coming up so we’re going to see more of that [kind of response].”

The ward committee was accused of failing to react adequately to the spate of killings last year, only joining residents during the wreath-laying ceremony. Now, residents are again calling on Abrahams to act against gangsterism.

Smith said his department was rolling out anti-gangsterism programmes in the area.

“No other city deals with gangsterism, and other metros don’t believe this to be part of their work. It is frowned upon when we try to do crime intelligence work and try to execute drug warrants. SAPS [the South African Police Service] gets a bit edgy,” he said.

Smith said the city-led task team consists of 60 metro police officers in an anti-gang unit. His department also employs a senior advocate to monitor the prosection of gangsters in court.

Zille’s spokesperson Michael Mpofu said the government was actively conducting awareness and safety programmes, which include neighborhood watch groups, CPFs and the walking bus. But he insisted that the provincial government’s role was “oversight only”.

Water-free games keep children ‘clean’

After-school rugby, cricket and football in Bishop Lavis have been cancelled since last April because of the amount of water needed to maintain the fields, the City of Cape Town argued at the time.

But at Bergville Primary, these extracurricular activities were meant to do much more than create sports stars and improve pupils’ agility, the principal, Aleem Abrahams, said.

“This is the only structure that these kids have, because after school they go home and they are alone there. The mom is working and the father is not in the picture. We said, to have a balanced pupil, they must perform in class and attend sports to keep them away from trouble.”

Bergville Primary boasts a local sports star among its alumni. One of the school’s former football players, Oswinne Apollis, secured a contract with Ajax Cape Town and travelled to Europe.

Abrahams said the school has four grade seven pupils who exhibit the same promise that Apollis did. But the boys have succumbed to the allure of local gangs and he blames the water restrictions that put paid to extramural sports.

“They’ve now started stealing meats at the shopping centre and I’ve heard they were lured into the local gangs here, which is really, really disappointing,” he said.

Gangsterism has been normalised in Bishop Lavis, Abrahams said. “It’s become so normal that, when the pupils hear shooting outside, they no longer take cover; they actually run towards the window because they want to see who it is.”

He fears that the structure that was afforded by after-school sports has been replaced by pupils spending time alone and becoming susceptible to being recruited by gangsters.

This is one of the reasons Abrahams has helped the Bishop Lavis Action Committee (Blac) to introduce a new after-school sport that requires no water: the indigenous games.

“It’s games like kennetjie, blikkies, hande klip, skoeloelie — all the games we used to play as kids in the townships,” said Victor Altensteadt, president of Blac.

Fortuin said primary and high school pupils needed the games because of the high number of young people involved in gang violence.

“Just last Saturday, while we were sitting in the office, someone came in and said: ‘Look, the guys are running across the soccer field with guns.’ Those kids are supposed to be involved in sports,” Fortuin said.