(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

The quality of diesel produced by PetroSA has become so poor that it is on the verge of losing its last big client, Shell South Africa, which could cost the oil company billions.

Several highly placed sources at PetroSA and its holding company, the Central Energy Fund (CEF), confirmed that the state-owned company has been placed on notice by Shell, which formally informed PetroSA in September of its intention to halt the procurement of diesel because of poor quality.

In particular, Shell is said to be concerned that the product turns to a waxy consistency in cold weather, putting engines at risk.

“As a result of our inferior product, the others pulled the plug last year and this year, and the only oil company left was Shell. Even they have now given notice,” a source said. “The complaint is that the product is off-specification and also that PetroSA is unreliable and the company has to pay penalties.

“The real problem is that revenue will take a knock,” said the source, who is not permitted to speak to the media.

The Mail & Guardian could not establish the value of Shell’s business. The sources said Engen, BP Southern Africa, Total and Chevron had already dropped PetroSA because of the same complaints about quality.

In a week during which state broadcaster SABC announced its intention to shed more than 1 000 jobs to save money, the revelations about PetroSA paint a picture of the dire situation in which the country’s key state-owned companies find themselves.

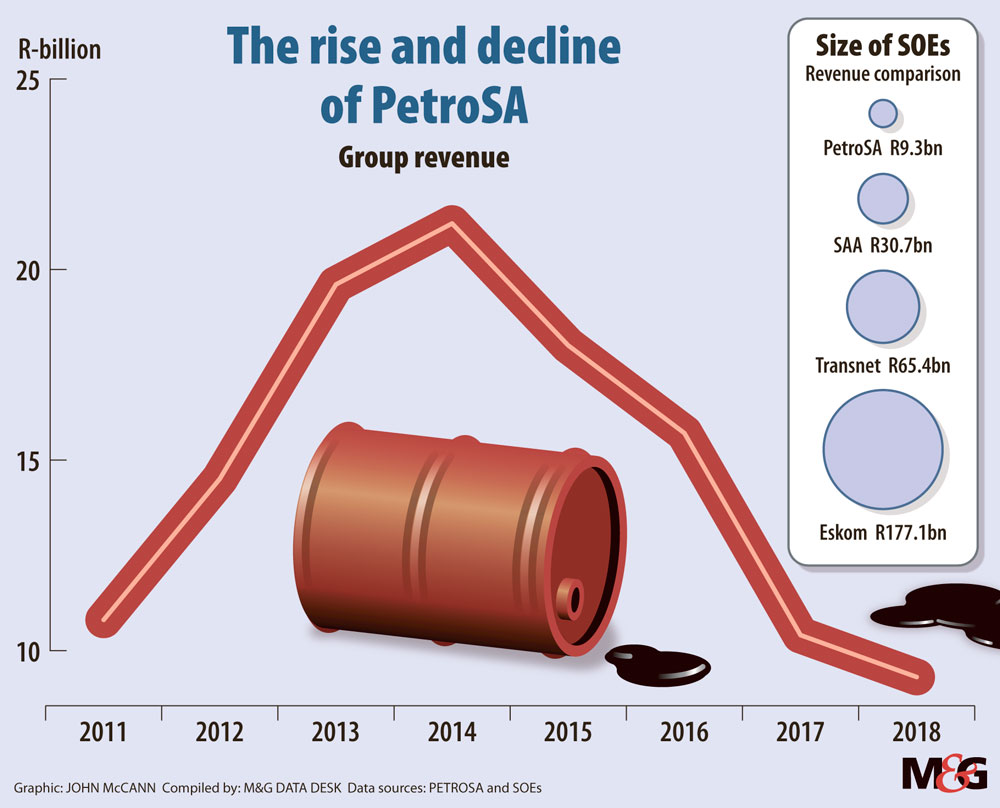

As with Eskom, Transnet, the SABC, SAA and its sister airline SA Express, the state oil company has been crippled by severe maladministration and corruption, which bleeds billions annually, as well as high debt levels. Group revenues declined by 43.8% from R21.2-billion in 2014 to just under R10-billion this year.

Finance Minister Tito Mboweni, in his medium-term budget speech, said the state needed to take a hard look at how these companies operate, adding that their continued decline posed a significant risk to the fiscus.

Internal documents from both CEF and PetroSA show that revenue generated from the sale of petroleum products, R9.6-billion in 2017, accounted for a significant portion of the CEF’s annual revenue of R11.5-billion. The CEF’s revenue was just under R21-billion in 2016.

This year, according to draft financials, PetroSA’s revenue has dropped by R300-million, and this is now under threat.

“We only had one big client left and that is Shell. Our product waxes because of the crude we are putting through a plant meant for gas,” another source said.

“In cold temperatures, it turns into wax and there were a couple of cars in the Southern Cape and the Free State whose engines had to be replaced … This product was traced to us and most of the big clients pulled the plug on us, saying they will never use us.”

Shell’s media manager Dineo Pooe said the company had not put PetroSA on any form of notice.

“Shell continues to have a good relationship with PetroSA, and continues to source a portfolio of products from PetroSA,” she said.

PetroSA did not respond to questions about Shell, but its spokesperson, Tumoetsile Mogamisi, said the company did experience “product quality problems” two or three years ago but they were resolved.

“Our customers are continuing to lift our products and we have good business relationships with them,” he said.

This latest setback threatens the existence of the state-owned company, which is still coming to grips with losses of R14.5-billion accrued in 2016 because of the failed offshore gas exploration project off Mossel Bay. Named Ikhwezi, its aim was to drill offshore wells to supply natural gas to PetroSA’s state-of-the-art gas-to-liquid (GTL) refinery in the town. It was expected to yield 242-billion cubic feet of gas from five wells at a cost R17.3-billion, but ended up producing gas from only three wells. Last year, the company said the wells were producing 30% of its total daily gas production.

In March last year, MPs serving on the portfolio committee on energy, warned PetroSA’s executives to get their act together, after the Ikhwezi losses, to avoid bankruptcy. And in May last year, PetroSA dismissed unconfirmed media reports that its board had asked for it to be placed under business rescue.

Currently, the company and the CEF is at an impasse with its government shareholder representative, the department of energy, over how to mitigate the effect of scarce gas resources.

The M&G reported in August that Energy Minister Jeff Radebe rejected a CEF plan premised on halting gas-to-liquid activities and ramping up the refining of crude oil to produce petroleum products. Radebe said the strategy, which included a commitment to procure 23-billion barrels of oil from an ally of former President Jacob Zuma, Kase Lawal, at a cost of R22-billion over five years, was not detailed enough.

Nigeria-born, American-based Lawal’s deals include a Public Investment Corporation investment in the dual-listed (JSE and Wall Street) Erin Energy, which earlier this year filed for bankruptcy after Nigerian authorities stopped the company from exporting oil because of a dispute about its licence to sell oil. He was exposed by the M&G for having appropriated discount Nigerian crude meant to benefit South Africa. Lawal also donated millions to Zuma’s education trust.

Radebe’s move exposed the rift between the minister and the CEF, and left executives and the board of PetroSA scrambling for another plan. Sources said they were yet to get it approved by the government, with just five months left before the end of the financial year.

PetroSA’s decision to refine crude oil at its gas-to-liquid facility has previously led to an increase in plant breakdowns and stoppages, resulting in losses of R500-million.

Internally, technocrats have questioned PetroSA’s continued determination to refine crude oil, especially Nigerian crude. PetroSA has previously said its focus on crude was driven by the drastically decreasing availability of affordable natural gas to feed into the plant.

The company is still buying crude oil, according to the sources, despite the government not having approved this and the inherent quality problems.

“They have already ordered two or three more parcels,” said a source.

“[Storage] tanks are full and they are unable to store this. Even this condensate is not known where it will go and the question is: ‘Why did they order this when Jeff [Radebe] already said it does not make sense?’

“The Mossel Bay plant is now no longer a GTL plant. These guys went ahead without government knowledge or approval and changed it to crude. They changed the certifications.”

In response to questions, Mogamisi said: “The PetroSA feedstock challenge is a result of our depleting natural gas reserves, which constitute feedstock for our gas-to-liquid refinery. Addressing the feedstock issue forms a critical aspect of PetroSA’s turnaround plan, which includes looking at all viable alternatives or supplementary feedstock options.”