Dulcie September was aware that she was in danger, but refused to obey orders from the ANC to leave France. (Robben Island/Mayibuye Archive)

A new effort is being made to uncover the truth surrounding the 1988 assassination of exiled ANC official Dulcie September in Paris, France.

September was gunned down outside the ANC’s Paris office on March 28. She was shot five times in the head with a .22 silenced rifle.

To date, French and South African authorities are no closer to answering questions as to who shot her, and why.

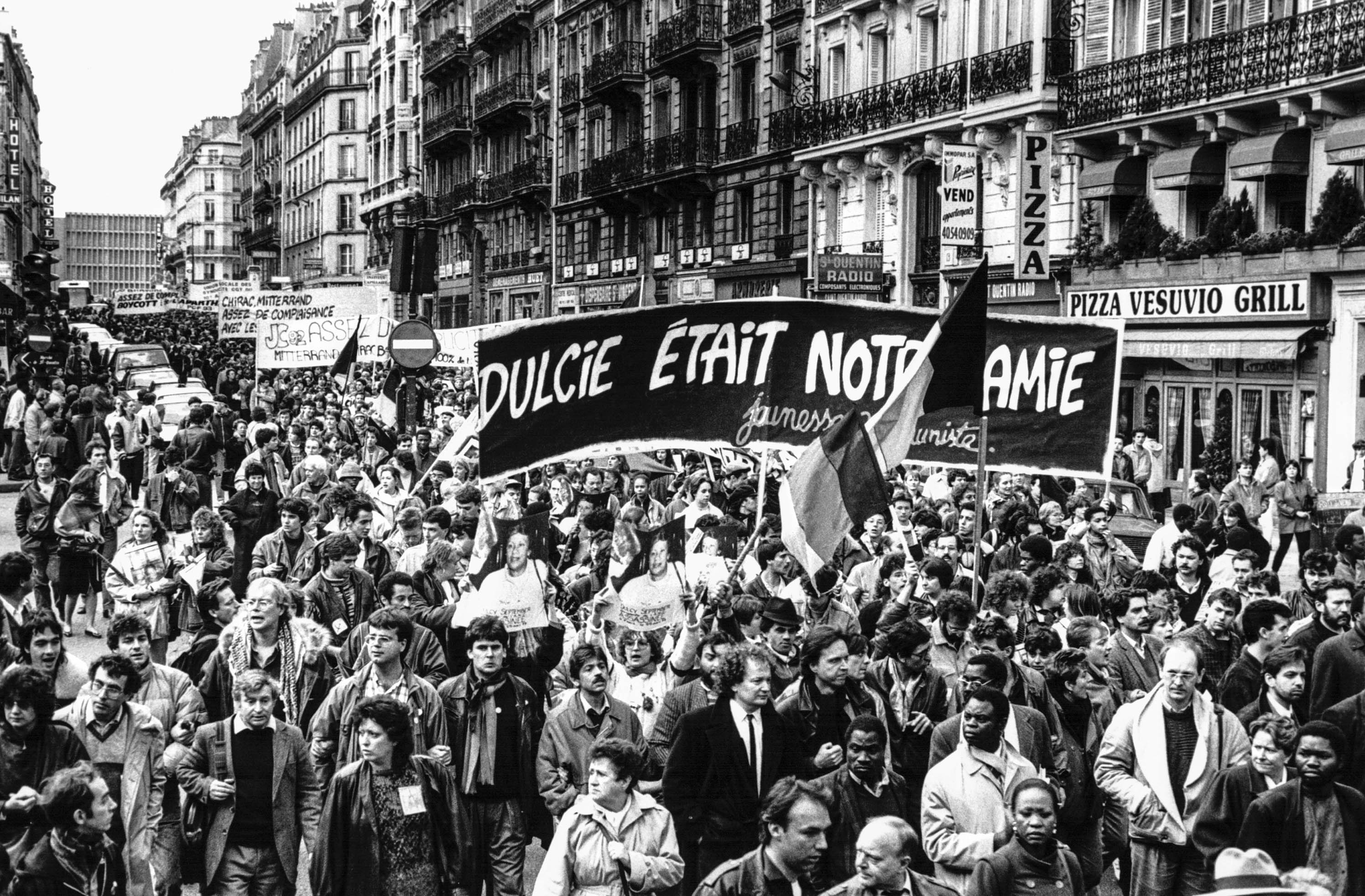

French citizens protest outside the South African embassy in Paris after September’s assassination. (Georges Merillon and Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images)

French citizens protest outside the South African embassy in Paris after September’s assassination. (Georges Merillon and Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images)

It’s believed that, at the time of her death, September was investigating alleged arms smuggling between France and South Africa. She was also a hugely irritating thorn in the side of the apartheid regime.

Now, new material is being released by a documentary podcast series produced by anti-corruption lobby group Open Secrets and podcast producers Sound Africa.

The launch coincides with the 31st anniversary of September’s death.

Producers Rasmus Bitsch and Neo Rakgajane say they’ve been combing through documents and evidence from countries as far afield as France and Belgium that may shed light on the assassination.

But they are holding out on trying to uncover who the hitmen were.

“It is not necessarily our prime objective … We’re not really trying to uncover who pulled the trigger and killed Dulcie September, but why she was killed. And for us that’s the more important question,” Bitsch says.

He says that, for them, September’s assassin is a weapon himself;an extension of the gun. What’s more interesting is who hired the assassin,and why September had to die.

The producers of They Killed Dulcie interviewed a range of September’s friends and comrades, and even former apartheid assassins, including Craig Williamson.

The former apartheid spy was awarded amnesty by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) for his involvement in various apartheid-era crimes, including the murder of anti-apartheid campaigner Ruth First by a letter bomb in Maputo, Mozambique, in 1982.

Rakgajane describes the experience of listening to Williamson detail how he went about his work as “chilling”.

“It was an incredible experience sitting across the table from him. It was a little window into the past. This man who was the bogeyman of my parents’ time. And here I am, sitting across the table, listening to him and how he did his work,” Rakgajane says.

But despite interviews with apartheid spies, there’s still speculation as to what may have led to September’s murder.

Even researchers from Open Secrets and Sound Africa say it would take a full inquiry by French and South African legal institutions to uncover the truth.

“Some of the documents that we’ve seen suggests she was busy looking into illegal arms trading between France and South Africa. She was investigating these things. We don’t know how much she knew for sure, because the documents that we have are just fragments. But it looks like she was far ahead in figuring out things that no one else had,” Bitsch says.

He says it’s disconcerting that not a lot has been done in South Africa to keep her name and struggle alive.

“She wasn’t only killed. She was erased from history and removed from society. We want South Africa to look at itself and its past,” he says.

September’s nephew, Michael Arendse, who’s spearheading the effort to uncover the truth about her murder, has welcomed the renewed focus on the stalwart’s life.

He says there are more and more people, other than her former comrades, who are trying to solve the mystery from three decades ago.

“As a family, we appreciate that Dulcie’s memory is being kept alive in various ways. This is a complex case. And we believe the way we get to the truth is to chip away at the block. Every play, every podcast, every documentary, every book will help to do that,” Arendse says.

But,he says, the bigger issue is to bring closure for so many South African families who’ve lost loved ones and are no closer to knowing what actually happened to them.

“Dulcie belonged to a community of people who gave their lives to the struggle, who gave their lives for what they believed in. So whenever we commemorate Dulcie’s death we do keep in mind those people, particularly the ones we don’t know of, whose names will never have books or plays written about them. Those anonymous contributions that are equally valuable to the struggle,” he says.

Arendse hints at the possibility of a legal challenge to force police to have the case of September’s murder reopened.

Bitsch and Rakgajane say answers need to come from senior officials of the former apartheid government, as well as ANC officials, about what really happened to September.

“Dulcie September was the highest-ranking ANC official ever assassinated. She was the only ANC woman assassinated in Europe. She appears to have been an incredibly principled person, who didn’t shy away from speaking up when she saw wrong, when bad things were even happening in her own movement.

“We don’t want to say: ‘These are the bad guys, and these are the good guys.’The past is complicated, and so is the present,” Bitsch says.