Billy Monk and a friend at the Catacombs nightclub in Cape Town where he was a bouncer. He took photographs as a side hustle, but they are now iconic records of unusual scenes in our history. (Don Ross)

Billy Monk: Shot in the Dark

Directed by Craig Cameron-Mackintosh

Since 1982, the year in which Billy Monk’s only photo exhibition took place and the year of his death, he has been known as a photographer for a small oeuvre of pictures he produced in the mid-1960s. They show the revellers of a very “alternative” (as it would come to be called) nightlife, sympathetically portrayed, and they are rough-and-ready in some ways, informal and improvised, but also composed with an artist’s eye.

Monk had been a small-time crook, was in a “common-law marriage” to a woman of colour, had two children, and worked as a bouncer at the Catacombs, an underground (literally and figuratively) nightclub, if that’s not too posh a word, near the docks of Cape Town. In the words of David Goldblatt in this documentary, it was “a dark, dismal place that stank of piss and beer”. It was a demimonde of sailors, prostitutes, queers and artists — and all races, apartheid law not yet having reached the dives of lower Cape Town. It featured coloured bands and was a space of racial and gender mixing that was seldom seen elsewhere in South Africa in that era.

Monk’s photos capture this world and its denizens and passers-through with a keen eye and a notable affection for his subjects. These are not images made by an outsider peering into an exotic enclave, but a participant record. He had an “intense connectivity” in that space, as critic Ashraf Jamal says here, and it shows in the images.

Monk took the pictures to sell to various clients of the Catacombs later — a bit of entrepreneurship rather than art production — and they weren’t exhibited for many years after they were taken. They were rediscovered half-accidentally, and he died just as his work emerged on to the public stage and was acclaimed for its historical and sociological importance, as well as its aesthetic qualities.

Monk’s story is eloquently told in Billy Monk: Shot in the Dark by commentators such as Lin Sampson, who wrote a book about him, and with significant contributions from his son, David, as well as fellow photographers. It’s a short (30 minutes) but informative and moving portrait of an artist who didn’t see himself as one. — Shaun de Waal

McQueen

Directed by Ian Bonhôte and Peter Ettedgui

British designer Lee Alexander McQueen had a meteoric rise, with his first show at age 23, and died by suicide when he’d barely reached his 40s. This documentary tells his story well, and at some length — it’s an hour and 50 minutes long. One might wish for a break halfway through, but it’s done with care, sympathy and some of the style to which McQueen accustomed the fashion world.

Alexander McQueen broke rules and made waves in the fashion world

Using home video, the testimony of collaborators, friends and family, as well as footage of his amazing fashion shows, it details his beginnings, explosive growth, and sad end. A chubby gay lad from the East End of London (his dad was a taxi driver), apparently inspired and given confidence by an adoring mother, he muscled his way into jobs that would teach him the basics of pattern-cutting and garment-making before doing a master’s degree at St Martin’s art college.

His graduation show was a shocker of a debut, having taken its inspiration from the Jack the Ripper murders of the 1880s. Later shows would continue to draw on this inner “darkness” of McQueen’s (freely admitted in interviews), becoming ever more extravagant. Later shows touched on rape as a theme, put models behind one-way glass or had a model in a white dress being sprayed with paint by vehicle-industry robots. He wrapped catwalk models’ heads in bandages or perched stuffed birds on them; he used a double amputee in one show, providing her with specially carved legs.

Although he kept his own label going, he went to work for Givenchy as chief designer and later did a deal with Gucci. He was doing 14 shows a year, and winning prize after prize, but the pressure was immense, as colleagues and family attest in the documentary. Drugs and depression killed him soon after his mother died of cancer in 2010.

McQueen is beautifully done, as befits its subject, with some of the ugliness included. A certain ugliness was integrated into McQueen’s sense of what beauty could be; it was part of an aesthetic whole, a larger beauty.

Mere prettiness couldn’t deal with the darkness that had to be there, that in some way drove him. The documentary is rather skimpy, though, on the details of his later, rather crazed years, perhaps out of a sense of discretion and propriety. Maybe it’s just voyeurism on my part, but I wanted more of the sordid details, and really, I don’t think McQueen would have minded. — SdW

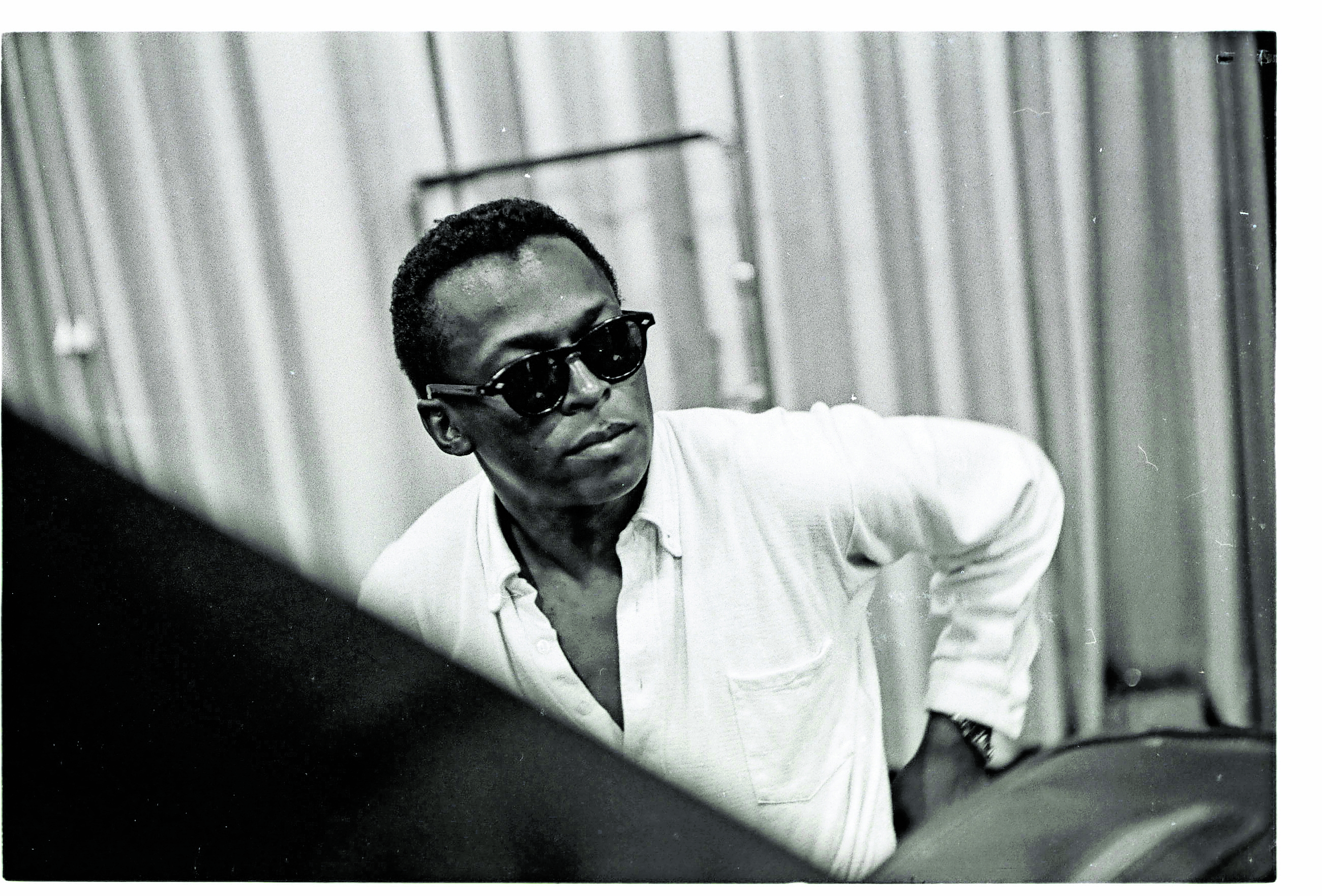

Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool

Directed by Stanley Nelson

Miles Davis was one of the most important figures in jazz after World War II and responsible for several key innovations in its development. This BBC Music documentary traces his full career, from his early bebop collaboration with Charlie Parker to his conjuration of a cool, West Coast sound in the late 1940s, through his development of modal jazz in the late 1950s, into his 1970s explorations of free jazz-funk (“cosmic jungle music”, as critic Greg Tate calls it) and, after his five-year “retirement”, his comeback as a megastar of the new, sleek 1980s pop jazz.

Miles Davis became one of the most important jazz figures, known for his key innovations in the genre

Davis had the widest possible view of what could be used and developed in his own musical production. “I wanted to see what was going on in all of music,” he is quoted as saying. (The voice-over, with text drawn from Davis’s autobiography, is performed in a convincing facsimile of Davis’s gravelly voice by actor Carl Lumby.)

He was a restless spirit, constantly reshaping his work and thus jazz as a whole. “If anybody wants to keep creating,” he said, “they have to be about change.”

This feature-length documentary traces these changes, though not in the granular manner that would satisfy a keen listener to Davis’s music. It repeats, for instance, the idea that Davis often entered recording sessions with only a few ideas scribbled on a piece of paper, but in both cases cited he also relied on collaborators for material. This rather shortchanges fellow musicians and composers such as Bill Evans and Joe Zawinul, who aren’t even mentioned. Key collaborators such as Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter and Ron Carter do, however, make some meaningful comments.

One imagines the filmmakers skimmed over the music production not just because time was relatively tight but because, rightly, they wanted to provide a sense of Davis’s overall cultural importance, as well as fill in something of his personal life and the effect that had on his work. The personal stuff is provided by friends and ex-wife Frances Taylor Davis, who died last year, as well as the partner of his last years, Jo Gelbard (other partners such as Cicely Tyson and Betty Mabry are spoken of but are personally absent). The sociocultural background is filled in rapidly, with fast montages of events in the public eye — the moon landing and protests against the Vietnam War, for instance. It does go by rather too fast for one to get a hold of it, though.

Culturally (and, inevitably, politically), Davis was a hugely significant public figure. When he began his career, jazz and sports were pretty much the only areas in which black people in the United States could achieve some social mobility and some public visibility outside the ghetto. And even that came at a price, as the story of Davis’s assault by a policeman, when he was already famous, illustrates.

But he took to his role as a successful black man in the public eye (“a real black motherfucker like me!”) with a vengeance. In the 1950s, before the American civil rights movement and at a time when Black Consciousness hadn’t yet articulated itself, he asserted his presence. As one commentator says here, as far as black pride in the 1950s went, “Miles was Exhibit A”.

The documentary can’t hope to encompass the full complexity of Davis the man and the musician, but it does a good job of introducing him to audiences who may have only a glimmer of what he was, while hinting at the deeper background waiting to be explored — and the magnificent music to be heard. — SdW

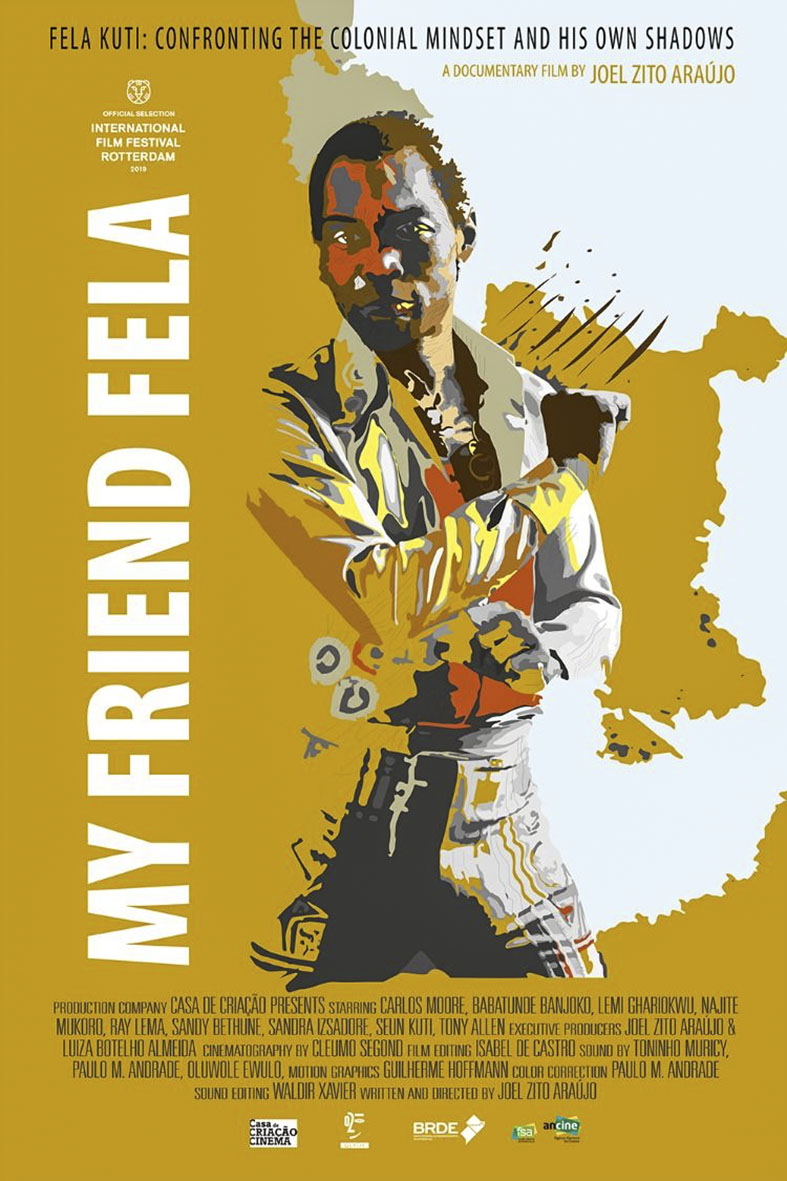

My Friend Fela

Directed by Joel Zito Araújo

My Friend Fela, which features writer and historian Carlos Moore, retraces some seminal epochs in Afrobeat founder Fela Anikulapo-Kuti’s life, and in some ways plays out as its title suggests.

The film is more about Moore, who wrote one of Kuti’s biographies titled Fela: This Bitch of a Life. Although it is a celebrated record of Kuti’s life, in no small part because it captured an estimation of his patois (and by implication his raw thoughts), it was also an ephemeral record of the man’s life, with little about his latter years.

Coming after documentaries such as Music is the Weapon and the solid and expansive Finding Fela, Moore and Araújo were sure to have their work cut out for them in presenting a new angle on Kuti and advancing it to benefit both neophytes and knowledgeable Kuti scholars.

While the “new” angle is there, particularly in how Moore centres Kuti’s life within the continuum of the Black Atlantic. This is done primarily through the use of an anchoring interview with singer and composer Sandra Izsadore. However, attempts to cohere the rest of Kuti’s life appear hodgepodge and hurried. There are many scenes in which Moore, who met Kuti during a trip to Nigeria, is running through a string of interviews as if for the mere exercise of jogging his own memory and justifying his role of “friend”.

The life of Fela Kuti is explored further in Carlos Moore’s new documentary about the musician, My Friend Fela

One, which could be seen as self-aggrandising, has him ask a close associate of Kuti’s how it was that Kuti had chosen him to write This Bitch of a Life, just for what seems to be a rehashing of Moore’s qualities for the camera.

What the documentary does expand on — perhaps with a slightly different slant to how other works on Kuti have dealt with this aspect — is just how much repression Kuti suffered at the hands of military governments in Nigeria and how they in turn turned him into a perpetrator of similar crimes in his own domain of Kalakuta, the compound where some of his wives and band members lived. There is a thread about how disciplinary beatings became an increasing aspect of life in Kalakuta, brought on by Kuti’s paranoia after several police beatings and the loss of his mother.

The framing of Kuti as a hero of the Black Atlantic starts off promisingly enough, with Moore speaking about his own history as an activist, time spent as part of Malcolm X’s security cluster during some of his travels and the advent of the Black Power movement, which Kuti caught in its potent infancy. It is not, however, a plausible thread throughout the film, making My Friend Fela a little too much like This Bitch of a Life: potent in parts, but a mere snapshot of the man. — Kwanele Sosibo

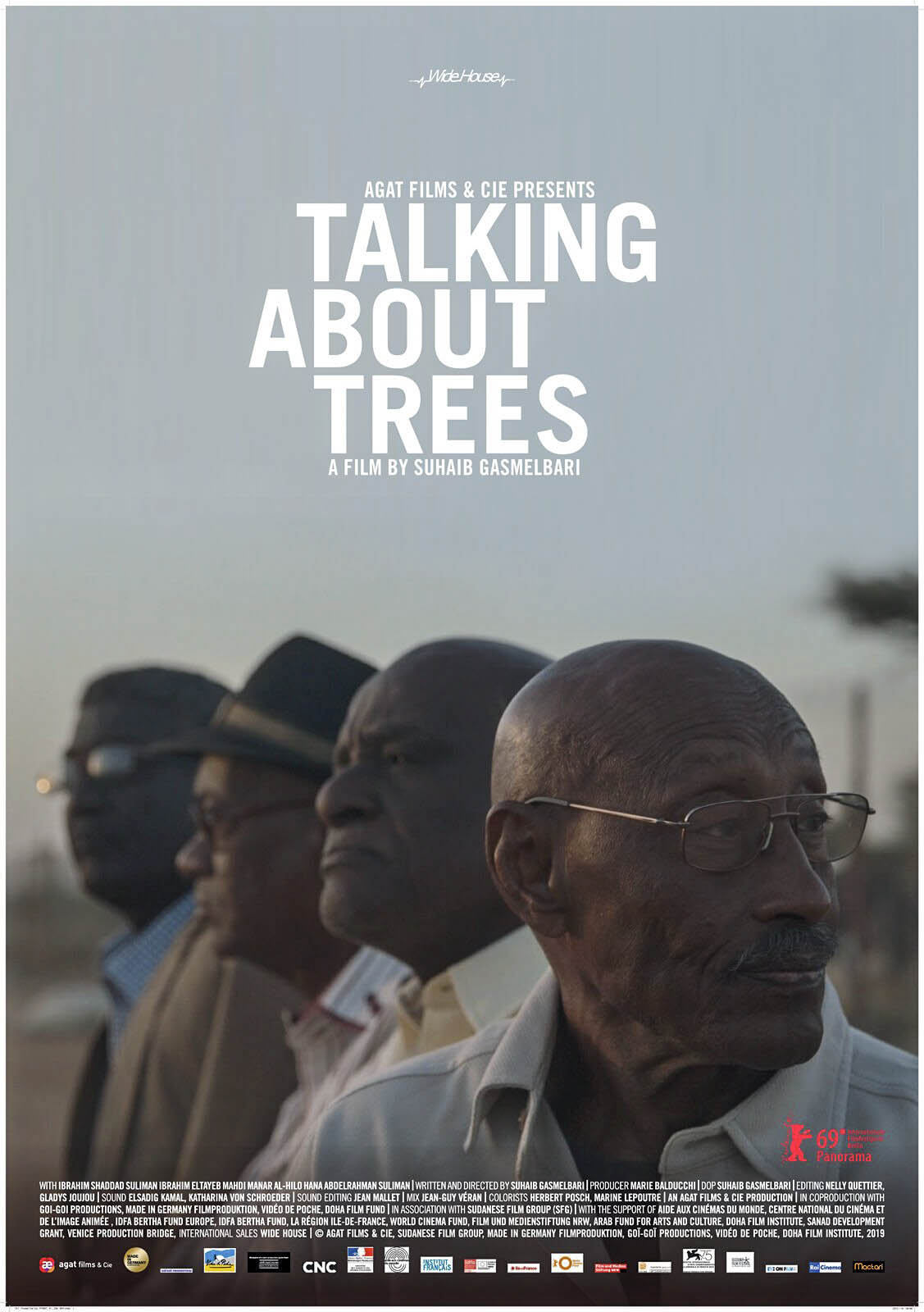

Talking About Trees

Directed by Suhaib Gasmelbari

In Talking About Trees, a group of Sudanese filmmakers ponder how to revive the culture of cinema in their country, in particular their town of Omdourman, which is close to the capital, Khartoum.

An endearing, no-frills documentary, the film homes in on the ageing filmmakers’ bond and the camaraderie that keeps them going as they go about attempting what is a historic reintroduction of cinema.

By zoning in on the filmmakers’ efforts and their own knowledge of cinema, we are let in on how the decree to quash Sudan’s film industry was a political one.

Directed by Suhaib Gasmelbari, this is a relatively quiet film in which some shots linger on the faces of the protagonists (who are members of the Sudanese Film Club) long enough for us to register the pain caused by crumbling infrastructure and the non-responsiveness of government officials tasked with keeping the lights on.

Sudanese filmmakers aim to revive cinema culture in a country where films were declared dissident in Talking about Trees

The film offers a unique view of contemporary Sudanese society. Over the course of 90 minutes, we learn of the country’s relationship with its artists, who are regarded with suspicion and relegated to the margins of society. We learn of the economic forces eating into its skin, with some of the interest in the old cinema that the film club is seeking to refurbish coming from the Chinese, who are seeking to convert it into a closed, self-contained community.

We learn of the bureaucracy of the government of the day, sending an emissary of the group from pillar to post before finally admitting the political motive in crushing the idea of an independently run cinema.

In a survey by the filmmakers as their efforts gain momentum, the people they interact with reveal how these iron-fisted tactics have affected their personal tastes, with most professing a preference for Hollywood-style action movies and Bollywood films.

But it is not as though the filmmakers — Suleiman Mohamed Ibrahim, Altayeb Mahdi, Ibrahim Shadad and Manar Al Hilo (many of them educated in film by the West) — are not aware of the dynamics at play. In a radio show in which several of the filmmakers are invited to speak about the history of Sudanese cinema, one of them explains how

the sudden death of a film hero is usually indicative of the concerted efforts of a traitor. The traitor that they eloquently speak of is self-explanatory.

Humour, however, is the film’s trump card. The closeness the filmmakers have is that of artists no longer having the blind idealism of what their efforts together can yield, yet knowing their efforts are noble all the same. “We are smarter, but they are stronger,” one of them says as they wade through the rigmarole of re-establishing the cinema.

Although they come up against stern bureaucracy, one emerges from the film with the feeling that perhaps the filmmakers have enough fight left in them to fight another day.

By highlighting the human experience above all, Gasmelbari reveals more of Sudan than meets the naked eye. He shows us its soul. — KS

The 21st edition of Encounters South African International Documentary Film Festival runs from June 6 to 16. For more info visit encounters.co.za