(Mike Hutchings/ Reuters)

NEWS ANALYSIS

(John McCann/ M&G)

The world’s poorest countries will be hardest hit by the effects of a changing climate. This is true in two ways. First, poorer countries — especially those along the equatorial belt — will experience the most dramatic climate variations. Various studies have predicted extreme cycles of floods and drought. Second, poorer countries have far fewer resources with which to mitigate the consequences of this changing climate.

Mozambique’s recent experience of Cyclone Idai, one of the most severe storms to have ever made landfall in Mozambique, is a stark illustration of just how unprepared developing world countries are to cope with natural disasters of this magnitude — and a reminder of how little help will come from the rest of the world.

But before we get to the response to Cyclone Idai, it is worth reminding ourselves about how richer countries respond to similar natural disasters.

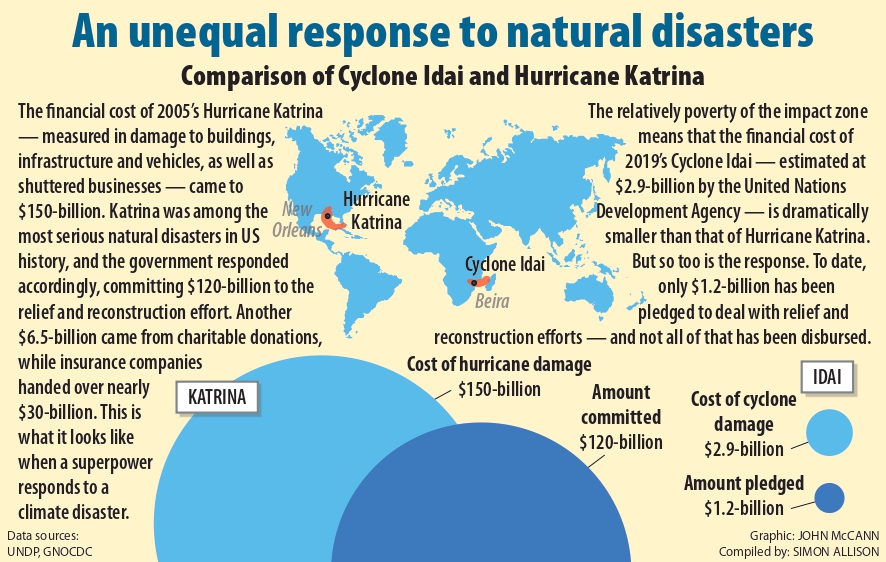

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina, a category 3 storm with winds of up to 200km/h, smashed into Louisiana in the United States. About 80% of New Orleans was flooded. At least 1 200 people were killed. More than a million people were displaced. The financial cost — measured in damage to buildings, infrastructure and vehicles, as well as shuttered businesses — came to $150-billion, according to the Greater New Orleans Community Data Center.

Katrina was among the most serious natural disasters in American history, and the government responded accordingly, committing $120-billion to the relief and reconstruction effort. Another $6.5-billion came from charitable donations, while insurance companies handed over nearly $30-billion. This is what it looks like when a superpower reacts to a climate disaster.

It is worth noting that, even with this massive financial commitment, the recovery from the hurricane was slow and uneven, and generated much criticism of both the local and federal government. Some of this criticism focused on the immediate aftermath of the storm, in which evacuees were kept in squalid, dangerous conditions in the Superdome, a New Orleans Stadium; other criticism focused on how reconstruction funds were disbursed.

The New Orleans mayor at the time is currently in prison for fraud, convicted for taking bribes from city contractors in return for rebuilding contracts.

Then-president Barack Obama said of Katrina in 2016: “What started out as a natural disaster became a man-made disaster — a failure of government to look out for its own citizens.”

If this was true of Katrina, how much more true will it be of Cyclone Idai?

This year, the Mozambican city of Beira and the surrounding Buzi district found itself in the path of Idai, a category 4 storm with winds of up to 175km/h. The city was 90% submerged. The storm travelled inland, flooding parts of Malawi and Zimbabwe. At least 1 300 people were killed, and some 1.8-million people across the three countries were affected.

So far, so similar to Hurricane Katrina. But Mozambique is not a superpower. Neither is Malawi or Zimbabwe. In fact, all three are among the poorest countries in the world, and were totally unequipped to deal with the impact of the storm.

The relatively poverty of the impact zone means the financial cost of Cyclone Idai — estimated at $2.9-billion by the United Nations Development Agency — is dramatically smaller than that of Hurricane Katrina. But so too is the response. To date, only $1.2-billion has been pledged to deal with relief and reconstruction efforts — and not all of that has been disbursed.

Poverty has compounded the suffering. One example: whereas many homeowners and businesses in the US were covered by insurance, to the tune of nearly $30-billion, this is not true of Mozambique, where the penetration of non-life insurance (homes, vehicles and belongings) is at just 1.3%.

Another example: most of the affected population in Mozambique are subsistence farmers. Not only was their home and land destroyed, but also their primary source of nutrition. This is never true of victims of disaster in richer countries, whose food comes through global logistics networks that can cope better with localised catastrophes.

And so, more than six months after Cyclone Idai struck, the recovery effort has barely begun. This week, for example, the UN children’s agency Unicef reported that nearly one million Mozambicans from storm-affected areas are facing food shortages and a nutrition crisis, including 160 000 children under the age of five. Ominously, Unicef warned that conditions are expected to worsen in coming months.

Even with $150-billion in reconstruction funding, and the resources of the world’s most powerful nation, the US struggled to respond adequately to the damage wrought by Hurricane Katrina. With just $1.2-billion in reconstruction funding, do the storm-affected areas of Mozambique stand a chance of getting back on their feet?