South Africa is on the path to a just transition. But does it make sense?

(Getty Images)

News Analysis

Towards the end of 2022, South Africa attracted global attention for contradictory reasons. It was the first developing country to present at COP27 a comprehensive Investment Plan

for the Just Energy Transition (JETP-IP) and it was the first country in the world whose minister responsible for energy policy accused the chief executive of the state-owned energy utility of treason.

The man who presented the plan at COP27 on behalf of South Africa was the same man leading Eskom who was accused by the minister, Gwede Mantashe, of plotting the overthrow of the state. Andre de Ruyter handed in his resignation shortly after on 11 December, citing “recent press reports” as the reason and the next day his coffee was allegedly laced with cyanide in an attempt to murder him.

We enter 2023 with an energy system that has never been in worse shape, without any certainty about who Eskom’s next group chief executive is going to be. We also cannot be sure how the three unbundled Eskom entities are going to be governed.

This week President Cyril Ramaphosa announced that the department of mineral resources and energy, headed by Mantashe, will take over responsibility for overseeing Eskom, but he also said things take a long time in government. We also don’t know whether Mantashe will be granted his wish to head up a new super-ministry of energy that is responsible for energy policy, Eskom and the process of unbundling Eskom into three entities for generation, transmission and distribution respectively.

Andre de Ruyter handed in his resignation. Photographer: Michele Spatari/Bloomberg

Andre de Ruyter handed in his resignation. Photographer: Michele Spatari/Bloomberg

Nor is there any evidence of a policy consensus between all the players in government about solutions to the energy crisis. In July, the president laid out a viable ambitious plan for resolving the crisis, including fully supporting the Eskom management team. There is little evidence that this remains the policy consensus in government today.

On 14 December, when asked about solutions to the energy crisis on news channel eNCA, Public Enterprises Minister Pravin Gordhan frankly stated that it was up to the department of mineral resources and energy (DMRE) to procure more renewables “rather than issuing press statements” — presumably the press statements that De Ruyter cited as reasons for his resignation. Gordhan has also publicly denied that De Ruyter is a traitor.

There are now also many different nodes of policy-related action on energy matters in the state sector. There is the energy department and public enterprises department, which have never pulled together as a unified political force. We now also have the department of forestry, fisheries and the environment (on climate policy, which is inseparable from energy policy), the National Electricity Crisis Committee (set up after the president’s July statement), Operation Vulindlela, the Presidential Climate Commission, the Task Team on Climate Finance and its secretariat, energy regulator Nersa and the Eskom board.

Consensus building for decisive interventions when there is a proliferation of policy-related actors becomes almost impossible. And as Eskom’s financial crisis deepens, so too does the leverage of its creditors grow to the point where they can effectively dictate conditions for further funding. And all these creditors have board-level commitments to only fund the energy transition, not fossil fuels.

Public Enterprises Minister Pravin Gordhan. Photo Delwyn Verasamy

Public Enterprises Minister Pravin Gordhan. Photo Delwyn Verasamy

Yet the world sees South Africa’s JETP-IP as a pioneering breakthrough. It was approved by the cabinet and therefore it is a cabinet-endorsed commitment to achieving net zero by 2050 through accelerated decarbonisation of the economy.

According to all credible models, this is certainly the cheapest and quickest way to

ensure energy security and therefore economic growth. But it is — contrary to official

statements — not consistent with the official energy policy, namely the outdated Integrated Resource Plan (IRP). South Africa waits with bated-breath for the energy department to produce an updated IRP.

In the meantime, despite the heroic patriotic efforts of the Eskom management team, the effects of state capture, gross inefficiencies, systematic sabotage, brain drain and ageing, poorly maintained infrastructures has resulted in the further decline in the performance of Eskom’s fleet of coal-fired power stations.

According to Clyde Mallinson, the energy availability factor of the Eskom fleet has declined from just below 90% in 2005 to just above 50% in 2022. We know that it dipped below 50% towards the end of last year.

(Source: Clyde Mallinson)

(Source: Clyde Mallinson)

According to the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, there was more load-shedding in 2022 than any previous year. By September, 5 761 gigawatt hours had been shed, more than double the amount shed in 2021 (2 521 GWh). As load-shedding worsened as the darkening year of 2022 drew to an end, the government became increasingly desperate.

Despite the absence of credible evidence, those who began to be heard by the government were those who argued that it was just a matter of “fixing the machines”.

Echoing people such as former Eskom chief executive Jacob Maroga and self-styled energy expert Ted Blom, Mantashe insisted there is plenty of energy available to meet demand — Eskom must just fix the machines. It is as simple as that.

But because De Ruyter is not an engineer, this is not going to happen, he insisted. In short, make sure the next group chief executive is an engineer. These statements by Mantashe, plus his statement about Eskom plotting treason, succeeded in creating the impression that we do not face a systemic problem — the problem is the individual who runs Eskom. This is useful, because it distracts attention away from the real cause of the problem — our energy policies and their implementation.

The Vosman informal settlement located near the Schonland Coal Mine in eMalahleni , part of the Highveld region turned over to mines and power plants. (Photo by Wikus DE WET / AFP)

The Vosman informal settlement located near the Schonland Coal Mine in eMalahleni , part of the Highveld region turned over to mines and power plants. (Photo by Wikus DE WET / AFP)

But in Eskom’s Integrated Report for 2022, the technical evidence that we face a systemic problem is made clear, albeit in muted language. “Due to the capacity constraints, EAF [energy availability factor] is not expected to improve noticeably over the short to medium term, as time is needed to execute reliability maintenance.”

What this implies is that this kind of maintenance means taking machines off the grid for extended periods of time — months, not days or weeks. But this is not possible when all the machines are being pushed to their limits to keep the lights on.

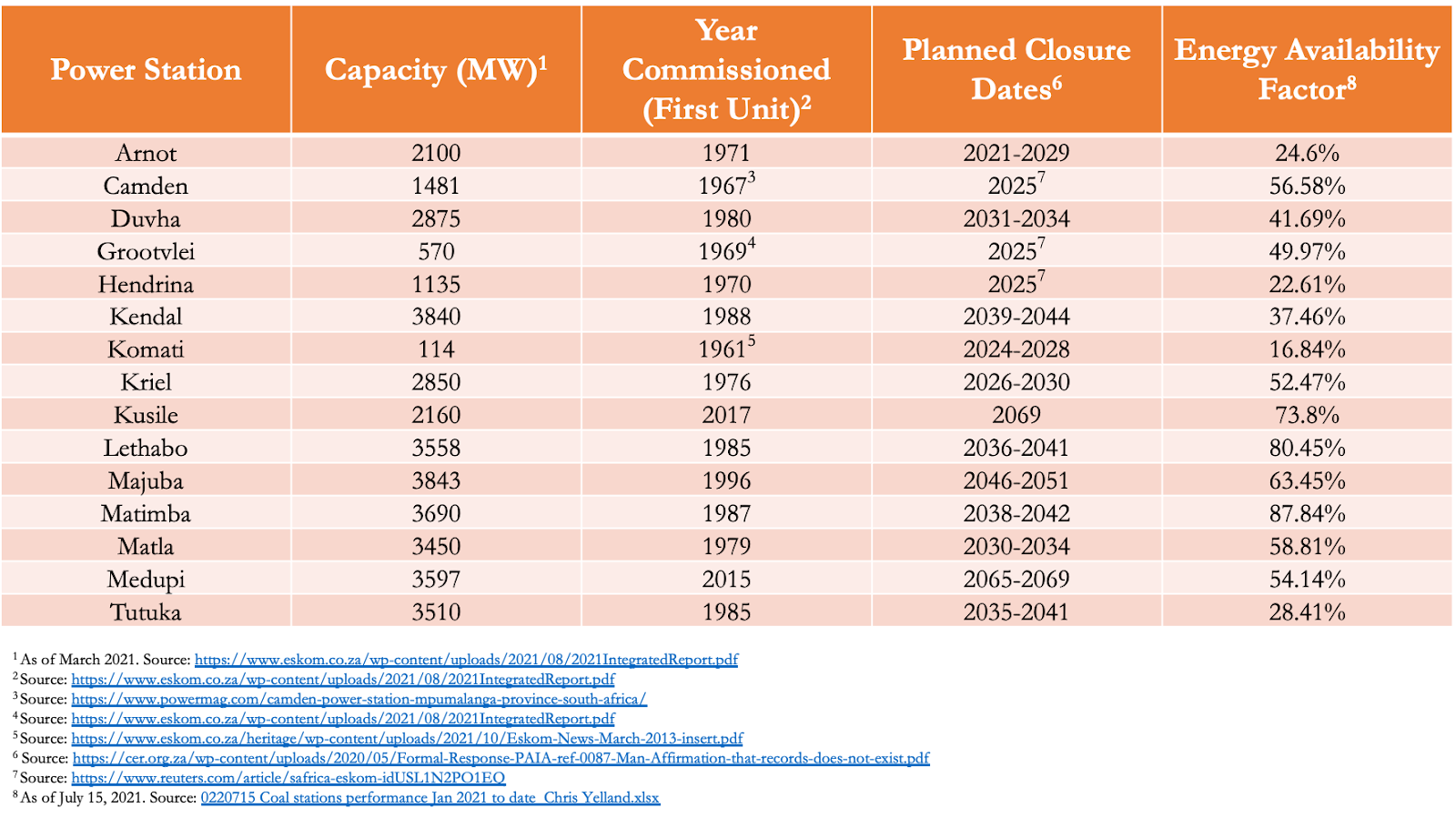

There are 90 electricity generation units in Eskom’s 15 coal-fired power stations. Altogether, Eskom operates 30 power stations using various technologies, and there are 86 utility-scale power plants operated by Independent Power Producers.

(Source: Eskom)

(Source: Eskom)

As reflected in the table below, many of the Eskom power stations are old. At least 14 500 megawatts of the available 47 246 MW must be decommissioned by 2030, with Komati power station already closed and others soon to follow. And, like a motor vehicle, for a power station to last, it must be serviced. Skipping regular maintenance as has happened under previous chief executives of Eskom (in particular Brian Molefe and Matshela Koko), means the performance goes into decline. Add to this corruption and sabotage, and even relatively young power stations such as Tutuka perform terribly.

To decommission old power stations and to fully overhaul the remaining ones so that they last long and perform as they should, it will be necessary to bring additional generation capacity on to the grid at scale. The only way this can happen affordably — at scale and within two to three years — is if an ambitious well-managed renewables (plus storage) build programme is executed with immediate effect. As the National Planning Commission proposed, 10GW of new generation capacity could end loadshedding in two years.

Although the energy minister has dragged his feet in this regard since his appointment back in 2019, in 2022 he took all the right decisions. Bid windows 5 and 6 are underway, and embedded generation with no limits is being implemented.

But the constraint that few predicted is now the capacity of the grid. Bid window 6 was supposed to yield 5 200MW (later reduced to 4 200MW), but less than 1 000MW was announced by the minister in November. The reason is that the grid is not ready to take on large amounts of additional generation capacity. It will cost R150 billion to upgrade the grid.

In short, until a substantial amount of new generation capacity from renewables is commissioned, Eskom will not have the space to properly fix the machines, and decommission what needs decommissioning. But that can only happen if renewables are procured through the energy department, with the concurrence of Nersa.

Even if that happens, unless the grid is upgraded to evacuate and transmit the new energy generated, it will not be possible to commission new generation capacity. Even if there was a permanent Eskom chief executive in place and there was policy consensus across government, these technical realities mean that 2023 looks like it could well be worse than 2022.

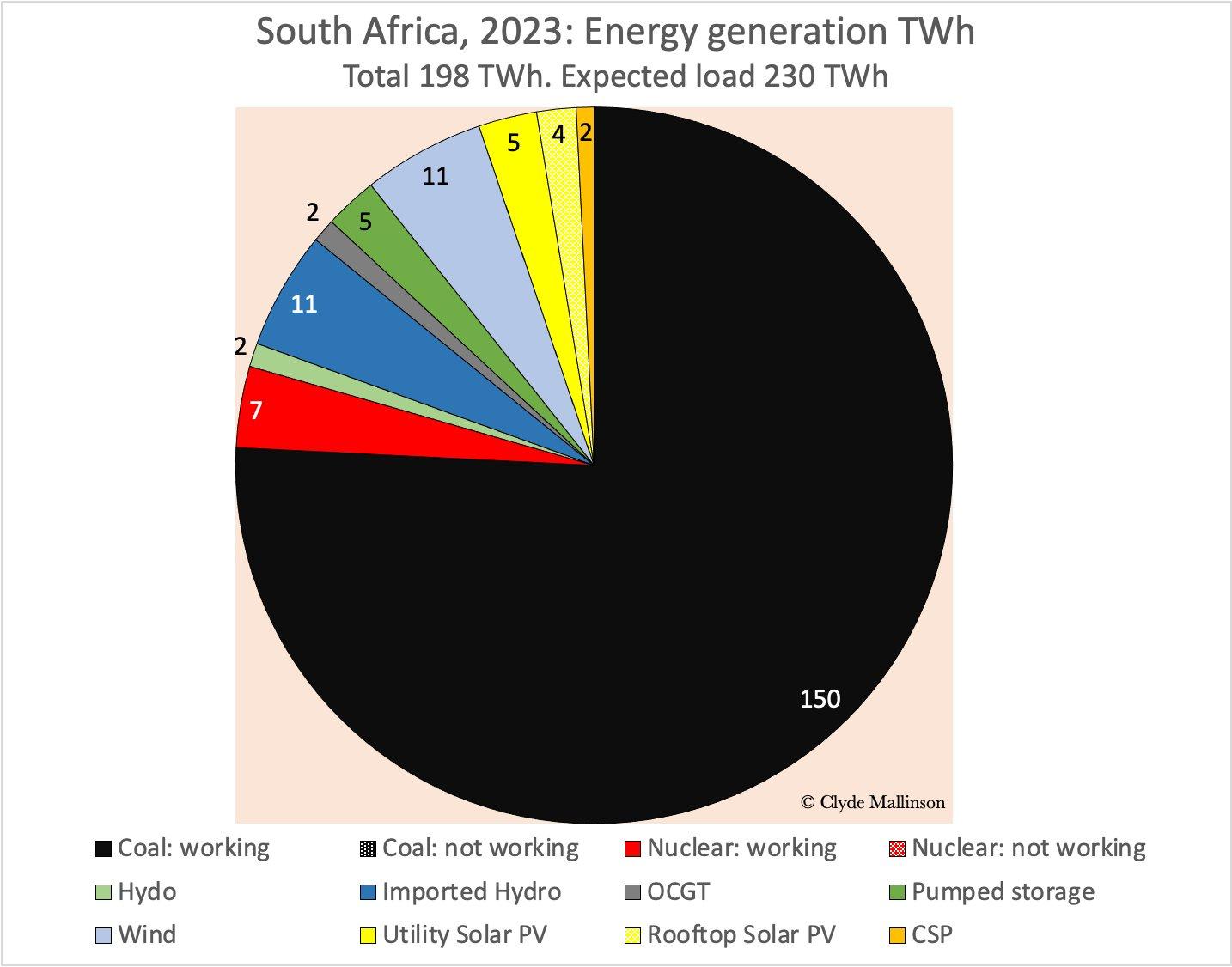

According to Mallinson, the expected real output from the crippled coal-fired fleet of power stations plus output from all other sources will most likely be 198 terawatt hours in 2023. The expected demand is 230TWh. The gap is 32TWh, which translates into permanent load-shedding at stage four levels through 2023.

A brief glance at Eskom’s “Likely risk scenario” in its 52 Week Outlook for October 2022 to October 2023 seems to confirm this pessimistic view.

(Source: Clyde Mallinson)

(Source: Clyde Mallinson)

The immediate actions to address the crisis should be as follows: adopt a systemic analysis of the problem, and focus on building a policy consensus rather than focusing on individuals as the sole solution to a systemic problem.

The treasury must make good the promise of the finance minister to take over between a third and two-thirds of Eskom’s debt, thus freeing up Eskom to allocate more funds to maintenance and the board of the National Transmission Company of South Africa must be announced immediately so that this entity can get up and running fast to attend immediately to the need to rehabilitate and extend the national grid, a task that could get compromised if it is saddled with too much debt.

Also, a clear strategic plan is required that builds on Eskom’s transmission development plan and describes in detail how the minimum of 10GW of renewables will be delivered by the start of 2025, which should be the target date for ending rolling blackouts and a clear multistakeholder high-level development plan for Mpumalanga is required that demonstrates how the just transition will unfold in ways that will not threaten the livelihoods of workers and communities dependent on coal.

Further, the JETP-IP needs to be fast-tracked so that the $8.5 billion is accessed on terms that suit South Africa, with the bulk of the loan funds used to upgrade and extend the grid, and the grant funds to support the just transition in Mpumalanga.

“The effects of state capture, gross inefficiencies, systematic sabotage, brain drain and ageing, poorly maintained infrastructures has resulted in the further decline in the performance of Eskom’s fleet of coal-fired power stations.” (Samantha Reinders)

“The effects of state capture, gross inefficiencies, systematic sabotage, brain drain and ageing, poorly maintained infrastructures has resulted in the further decline in the performance of Eskom’s fleet of coal-fired power stations.” (Samantha Reinders)

A new group chief executive for Eskom must be appointed, but only as part of a wider policy consensus that mandates him and the Eskom board to implement in accordance with the JETP-IP and updated IRP, including timelines that bind all regulatory bodies, especially Nersa.

The Eskom board and management need to set a realistic average energy availability factor of 60% over the next two years (not the unrealistic 75%), and provide South Africans with an understandable plan in non-technical language for how this will be achieved.

A regulatory regime is needed that ensures that we do not run two separate renewable energy delivery programmes with contradictory outcomes that could compromise the goal of 10GW in two years — one through the Renewable Energy IPP Procurement Programme and the other through the market for “embedded generation”.

A consortium of public and private financial institutions is required that will come up with creative ways to resolve the financial crisis that underlies the energy crisis and regulatory obstacles that prevent wheeling, municipal procurement of renewables, and the rapid rollout of rooftop solar photovoltaic systems should be identified and removed.

Such a strategic plan could demonstrate what a five-year pathway looks like, and what exactly is expected of the government.

Mark Swilling is a professor of sustainable development and the co-director of the Centre for Sustainability Transitions at Stellenbosch University