Photo by Delwyn Verasamy/M&G

Last month, the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators project released an update of their composite measures of governance performance. There have been more than 20 updates to the project since it began, with the database stretching back to 1996.

The project scores countries on six dimensions of governance: control of corruption; government effectiveness; political stability and absence of violence; regulatory quality; rule of law and voice and accountability.

The current version of the index draws from more than 30 data sources to create the measures. Most of these sources are either survey data from organisations which report on citizen sentiment, such as Afrobarometer, or country reports compiled by expert information providers, such as the Economist Intelligence Unit. These measures, and others like them, such as the Mo Ibrahim Foundation’s Ibrahim Index of African Governance, are firmly established.

It is therefore worth reflecting on the merits and limitations of these instruments in illustrating the state of governance, especially in the African context.

At a basic level, their emergence reflects the notion that “governance” is something we can quantify and that it is desirable to consider governance in these terms.

That is, we can gain an accurate picture of the state of governance in an area from collecting, measuring and combining useful statistics about a variety of governance issues. Examples of such statistics include finding out how many citizens in a specific area trust their head of state and the extent of the access they have to clean water.

The greatest advantage gained by viewing governance as something measurable is that it enables us to compare by time and place. It is undeniable that governance, in both practice and effect, changes over time.

But without being able to measure this change, our ability to analyse this change is limited. Having the ability to measure governance trends permits policy-makers and analysts to determine whether a society is improving, stagnating or worsening. The value gained from this increases the more regular and accurate a measure is, as this provides an indication of the rate of change.

Likewise, being able to differentiate between better governed and worse governed places offers critical insight into which places require a policy “course correction” and which should “stay the course”.

Since most quantitative governance indicators observe governance at the national level, this invariably means the comparison happens between national policy outcomes.

In practical terms, being able to make these governance comparisons helps us explain, for example, why Botswana has overtaken South Africa on the measure of GDP per capita. And this despite South Africa recording a higher average income level 25 and even 10 years ago.

The academic material on the subject is complex but increasingly it seems clear that — on average —democracy fosters inclusive governance institutions and these reap economic dividends over time.

Recognising that most quantitative measures of governance assess quality at the national level, we at Good Governance Africa have taken the initiative to create our own instrument, the Governance Performance Index, which measures governance at the local level.

This scoring and ranking instrument, which evaluates the state of local governance in South Africa, has helped us to understand critical patterns and links within society. This includes detecting that better service delivery outcomes were linked with higher voter turnout in last year’s municipal elections.

Being able to measure governance in this way is important in Africa, where the quality of governance and the implementation of evidence-based policy-making can make a difference in vital areas such as education, health and the prevention of conflict.

Some shortcomings

This is not to say the notion that “governance is measurable” is without its flaws. Some are philosophical, while others relate more to technical limitations.

Theoretical limitations are most relevant to consider in cases where the quantitative analysis is not supplemented by rigorous qualitative analysis. Such oversight leaves the policy-maker or analyst with an idea of what the overarching governance patterns and trends are but little capacity to explain “why and how” they have come to be.

This is why the relationship between the more traditional, qualitative methods of social science and the newer, quantitative methods should be one where they complement one another, rather than one where they are used in opposition to one another.

A more practical constraint is posed by the fact that any measure of governance quality is only as good as the data that was used to create it. Historically, this has been a particular concern in Africa, with statistical coverage in rural areas often lacking.

While there are still instances where this is a problem — especially in “fragile states” — it is undeniable there has been progress in terms of the accuracy of data throughout the continent, especially over the last 50 years.

The effect of this is governance indicators themselves have become more accurate over time.

What the measures tell us

The variables reported by the Worldwide Governance Indicators are effectively outcomes of underlying institutional dynamics that have evolved over time.

And while they do not necessarily tell us anything useful about those underlying dynamics, we still believe comparing these outcomes and their relationship to economic performance, for instance, is worthwhile. Once a pattern is identified, academics and policy-makers can try to ascertain the underlying drivers.

To demonstrate just one important pattern, at Good Governance Africa we have developed an interactive visual tool we call the Governance Coefficient. It enables us to observe how the relationship between two Worldwide Governance Indicators measures has influenced economic development in recent decades.

The two measures are government effectiveness and voice and accountability. In line with the theory of long-run development presented by economists Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson in The Narrow Corridor, we find economic dynamism rises in societies which possess both a capable state and an active citizenry.

One needs the two to work together, otherwise states ride roughshod over their citizens; the opposite can also play out.

As one of Africa’s largest economies, it is useful to consider what these governance indicators can tell us about the state of society and governance in South Africa.

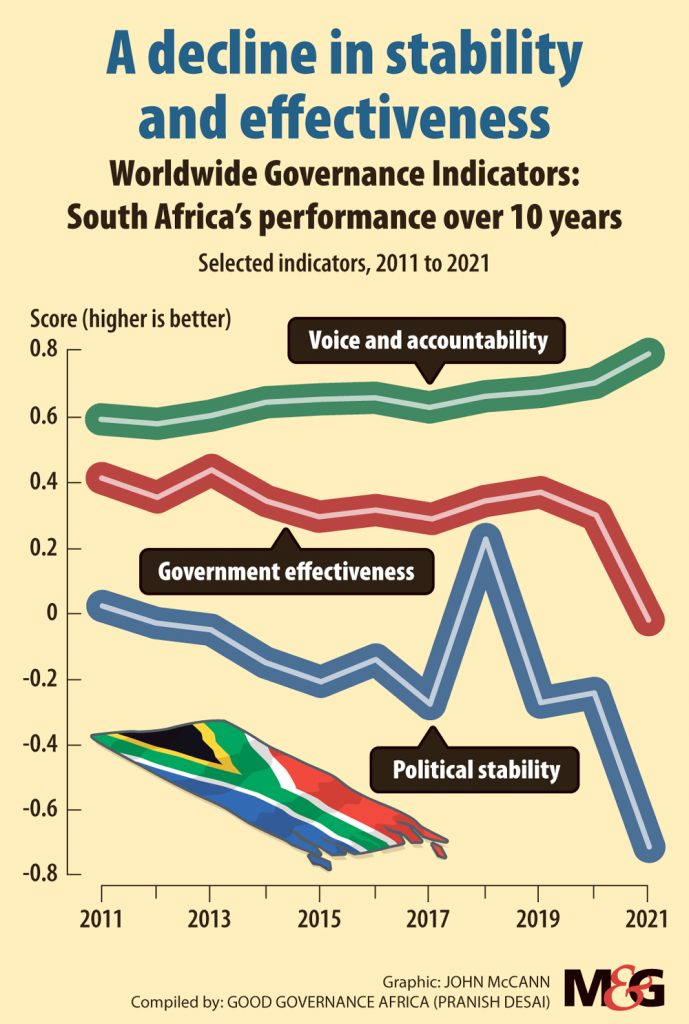

Reflecting the strength of civil society, South Africa consistently performs well on the measure of voice and accountability, where it ranks second-best in Africa. By contrast, its performance in government effectiveness has seen a substantial decline over the last 10 years.

Yet, as the graphic shows, even this decline in government effectiveness pales compared to the trend we see in its performance on the measure for political stability and absence of violence. Whereas in 2011, South Africa ranked 14th out of the 54 African countries on this measure, by last year it had dropped to 28th.

The overall drop is even more concerning when we consider the average African score on this measure also decreased over the same period, implying South Africa’s deterioration has happened at a faster rate.

And while South Africa’s 2018 score for political stability momentarily rose after Cyril Ramaphosa assumed the presidency, the subsequent decline has been even more precipitous than the one observed between 2011 and 2017.

This backsliding culminated in the wave of civil unrest in July last year, which a subsequent expert panel report concluded was characterised by widespread governance, institutional and intelligence failures. According to the report, more than 350 people died as a direct consequence of the upheaval, with the overall cost to the economy estimated to be north of R50-billion.

At present, these governance indicators provide a warning for African countries which have experienced backsliding. Put simply, without reversing these concerning trends, South Africa risks having governance failings continue to ripple through society to further devastating effect.

Pranish Desai is a data analyst within the governance insights and analytics programme at Good Governance Africa. His research interests include African governance, quantitative social analysis and political geography.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Mail & Guardian.