Dissatisfaction with the failure to deliver adequate services often results in protests, with Johannesburg being the country’s protest capital. Photo: File

When about 60% of Johannesburg had water outages earlier this year, the crisis highlighted the city’s significant infrastructure problems. These are caused — and subsequently exacerbated — by poor governance.

Across South Africa, confidence in government institutions is declining. Surveys show that public dissatisfaction with local councils’ capacity and willingness to listen and respond effectively is particularly pronounced. This dissatisfaction is often expressed through protests about poor service delivery, especially in Gauteng, South Africa’s economic and urban hub.

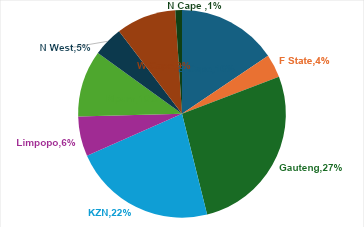

Municipal IQ, a specialised local government data and intelligence organisation, runs a Hotspots Monitor which found that Gauteng accounted for 27% of all service-delivery protests in 2022, the highest in the country.

Johannesburg, located in Gauteng, is the country’s most populous city and the country’s protest capital. Residents regularly take to the streets over various issues, including water shortages, electricity cuts and waste collection failures.

Johannesburg’s third share of South Africa’s GDP means protests can have widespread ripple effects nationwide. KwaZulu-Natal follows Gauteng, with 22% of protests, while the Eastern Cape registered 16%.

As Kevin Allan, managing director of Municipal IQ, noted, “It is no surprise that Gauteng continues to dominate protest activity in the country as frustration levels around local service delivery remain high in this highly urbanised province.”

In effect, Johannesburg has become a place where declining trust in councils translates directly into expressions of dissatisfaction.

[Source: Municipal IQ Municipal Hotspots Monitor]

The reality is that local municipalities will continue to play a central role in South Africa’s democratic future. National stability can, therefore, be seen as a partial reflection of their stability. But public discourse frequently remains focused on national leadership, despite practical issues related to service delivery are often addressed at the community level, which is also where the political responsibility lies.

Ballots may be cast at election time, but they are shaped by people’s daily experiences. When taps run dry or rubbish piles up in the streets, those frustrations feed directly into how citizens judge democracy and, ultimately, how they vote.

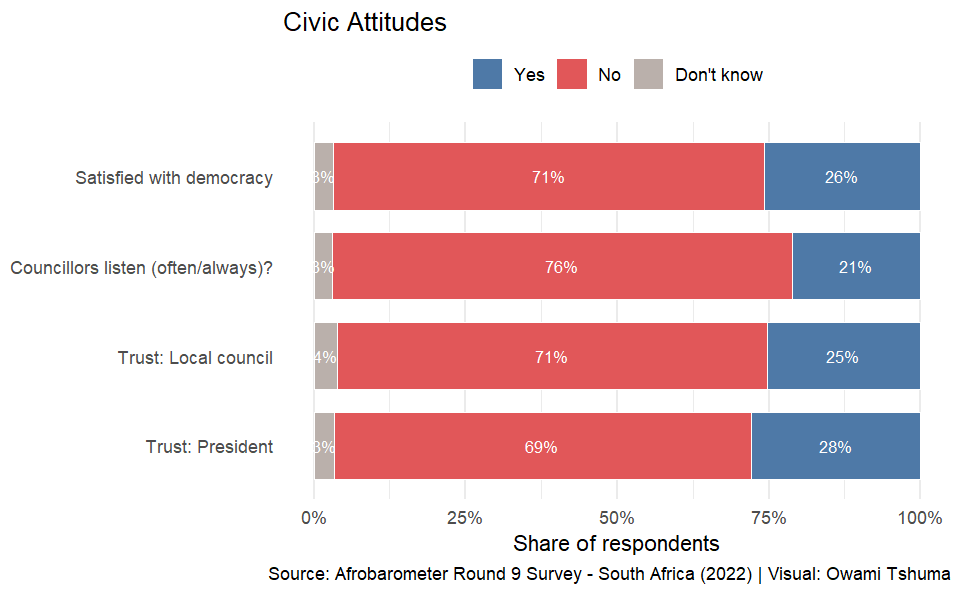

The gap between where politics is debated and where it is experienced is reflected in survey data. The Round 9 survey by Afrobarometer showed notable declines in South Africans’ trust in institutions, political participation and satisfaction with democracy. These declines indicate where the democratic repair needs to begin — with regaining the public’s trust.

The results show that 69% of the respondents expressed little to no trust in the president. Only 25% of respondents reported that they trust local government councils “somewhat” or “a lot”. The majority, 71%, expressed little or no trust, while 4% were uncertain.

When asked whether local councillors listen to people, 21% of respondents said they do, while 76% believe councillors “never” or only “sometimes” pay attention. This shows that South Africans doubt both national and local leadership, but they are especially sceptical about their local government councillors’ responsiveness.

Simultaneously, there is a decline in satisfaction with democracy in South Africa, with 71% of respondents feeling that it is not a democracy at all or are dissatisfied with how it functions in the country.

The perception that local councillors are not responsive to the most pressing concerns of residents, combined with ongoing unresolved issues, often leads to public frustration spilling into the streets, resulting from the gap between representation in theory and responsiveness in practice. This serves as a reminder that the biggest threat to democratic credibility is not only at the top, but also in the places where residents feel most neglected.

When institutions fail to listen, citizens rarely stay quiet. In South Africa, protest has become a visible and common form of accountability at the local level.

Johannesburg shows the chaos that results from this political instability. Over the past few years, the city has seen a high turnover of mayors, driven more by fragile coalition politics and internal party conflicts than by local accountability. This high turnover has led to governance paralysis — projects remain unfinished, plans remain on paper and residents are left waiting for essential services to be delivered.

This situation is particularly disheartening, given the constitutional mandate that municipalities serve as the core of “developmental local government”, responsible for providing basic services and fostering social and economic growth.

Furthermore, Johannesburg metro’s ranking in Good Governance Africa’s Governance Performance Index shifted from third place out of eight metros in 2021 to fifth place in 2024, reflecting a decline in its overall governance performance compared with other metros. When local councils stumble, they betray the very promise of democracy, which affects people’s everyday lives.

The auditor general’s annual reports make the connection that poor financial control in municipalities is not just an abstract failure, but directly undermines service delivery. In the 2023–24 Citizens’ Report, auditor general Tsakani Maluleke cautioned that weak and inconsistent corrective action not only distorts balance sheets but also affects the “lived realities of South Africans”.

The national picture is bleak, with only 41 out of 257 municipalities (16%) achieving clean, unqualified audits. Although 59 showed improvement, 40 regressed despite years of interventions.

Johannesburg illustrates the problem starkly. Governance expert Paul Berkowitz noted that it was the only metro that required remedial audit assistance from the auditor general’s team because the city’s initial financial statements “were not good enough”. For residents, this is not merely an administrative embarrassment, but a reminder that, when a city cannot provide credible accounts, it cannot convincingly claim to deliver services.

If Johannesburg aims to move beyond managing crises, solutions should move beyond recognising failures. It should implement practical and actionable measures to improve how the city is managed and structured. Local government must be given the means to act, the requirement to act, the obligation to be transparent and the responsibility to listen.

As mentioned, the city has cycled through eight mayors in six years, leaving projects abandoned midstream and undermining public confidence. This instability highlights why executive mayors require more than ceremonial authority; they need the tools and consistent performance management to ensure effective governance.

Maluleke has been clear about where responsibility lies. “Mayors, councils and executive authorities are failing to fulfil their legislative responsibilities,” she said, adding that no mayor should tolerate repeated negative outcomes. She held provincial leadership equally accountable for “setting the tone” for clean governance. “If every single player in the ecosystem did their part consistently well, we would have very few problems,” she argued.

Transparency is just as crucial. One of the simplest ways to rebuild trust is through transparency. When information is hidden in lengthy reports, residents assume the worst — that money is wasted and promises are empty. But, when information is shared openly and in plain view, people can see when progress is being made.

Platforms such as the Gauteng Water Data Hub demonstrate the power of this approach. It provides real-time updates on supply and shortages, thereby reducing suspicion and offering residents clarity. Imagine the same for electricity outages, housing allocations and waste collection.

Accessible dashboards are not just about efficiency, they are also about demonstrating a commitment to citizens by making “public” information public in practice. When residents can track what the government is doing without needing specialist knowledge, trust begins to shift from scepticism to confidence. South Africans do not just want to be heard at the ballot box — they want to see their daily lives improve, one service at a time.Owami Tshuma is a junior data analyst at Good Governance Africa’s Governance Insights and Analytics Programme.