No itch unscratched: Lou Reed had a 55-year recording career that transformed the rock genre with a host of innovative albums. (Alessia Pierdomenico, Reuters)

In December 1964 Lou Reed released what was effectively a solo single under the name the Primitives. Do the Ostrich wasn’t the first record to bear his name. For a few months he’d been churning out made-to-order songs for Pickwick, a label that specialised in bargain-basement albums ripping off that period’s prevalent pop styles. Before that, his teenage band, the Jades, had released two entirely unexceptional doo-wop tracks in 1958 and two years later he had chanced his arm as a solo singer, recording in the perky, post-rock ’n roll style that predominated in pre-Beatles America.

But if it wasn’t the first Lou Reed record, Do the Ostrich was certainly the most remarkable at the time. It was meant to be a quick knock-off of a novelty dance fad single, in the vein of Chubby Checker’s It's Pony Time.

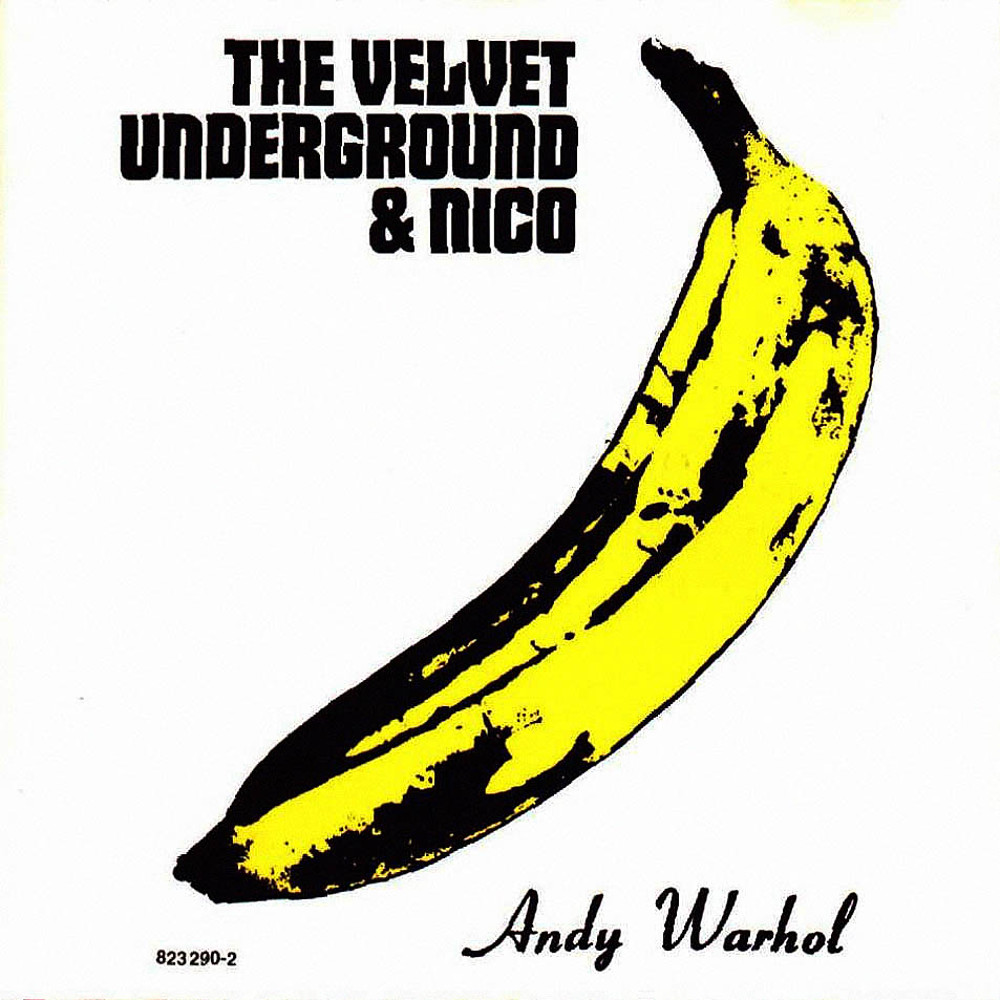

But there its resemblance to a chart hit ended. Reed had tuned all the strings on his guitar to the same note, resulting in an intense, clangourous din. He’d later use the same trick on the Velvet Underground’s Venus in Furs and All Tomorrow’s Parties. The lyrics aren’t trying to start a novelty dance craze at all, they’re the sound of a drugged-out New York smart-ass sneering at anyone stupid enough to indulge in a dance craze: "Take a step forward, step on your face."

There isn’t a chorus, just a load of unsettling screaming. The ultra-primitive rhythm builds to a chaotic, pounding middle section that sounds remarkably like something off White Light/White Heat, still one of the great challenging listens in the classic rock canon 45 years on. How anybody came to the conclusion that this was headed for the Top 10 is a mystery.

It's an odd footnote to his career, but Reed never seemed embarrassed by it. Quite the contrary, on the Velvet Underground’s debut album he was credited as playing "Ostrich guitar"; in some of the last interviews he gave, a year before his death, he was still happily expounding on the power of the one-note "ostrich tuning".

Perhaps it was because, in its own weird way, Do the Ostrich was Lou Reed in a nutshell: it should have been straightforward, but Reed had done the opposite of what he was expected to do. In the short term the result was commercial oblivion: the single sank. In the long term Reed had found his metier. He would make a career out of doing the opposite of what people expected. He was unknowable, which, you suspect, is exactly what he wanted to be: "I don’t have a personality of my own," he told one interviewer flatly.

Or perhaps the contrariness was his personality writ large. A friend who knew him when he was Lewis Reed, the eldest son of a middle-class Long Island Jewish couple, told his biographer, Victor Bockris, that Reed had a pronounced case of shpilkes: his nervous energy was such that "he has to scratch not only his own itch, he can't leave any situation alone or any scab unpicked". Certainly, from the start, he specialised in confounding the expectations of even his closest collaborators. In the Velvet Underground John Cale had Reed pegged as "very full of himself and faggy … queen bitch", perfectly at home among the barbed gossip and camp put-downs of Andy Warhol’s Factory.

The minute he’d manoeuvred his creative partner out of the band, however, the man Cale called Lulu started writing songs in which he pined for his college sweetheart, Shelly Albin, like a lovesick teenager. Pale Blue Eyes is about her, as is Beginning to See the Light and I Found a Reason.

In their Cale years the Velvet Underground themselves could sound like a band intent on overturning the established order of rock ’n roll, almost literally: on their 1967 debut European Son bursts into frantic chaos with a verbatim crash, like the contents of an upended table hitting the floor.

But Reed wasn't a musical iconoclast, he was a scholarly rock fan, a classicist who thought You’e Lost That Lovin’ Feeling was "the best record ever made". Ten minutes before the crash on European Son you can hear Reed signpost his love of Motown by opening There She Goes Again with a musical quotation from Martha and the Vandellas's Hitch Hike.

Perhaps that’s why they ended up being so influential: because the Velvet Underground sounded like a rock 'n roll band, even when they sounded like no rock ’n roll band had ever done before.

Anyone who thought that things might become more straightforward and less contradictory when Reed became a solo artist was in for a major disappointment. The enduring image of Reed became that of the self-styled Rock 'n Roll Animal: tough, streetwise, clad in black leather and fuelled by amphetamine, possessed of an attitude that went far beyond rock-star arrogance or insouciant cool into the realms of real nastiness and cruelty.

But Rock'n'Roll Animal was the possibly ironic title of a 1973 live album Reed apparently had no great love for. The stuff that reinforced that image – I’m Waiting for the Man, Street Hassle – was matched by songs of real tenderness, not in the grudging tears-of-a-tough-guy style, but open and honest and touchingly fragile (see Femme Fatale’s ruined suitor warning others off to Coney Island Baby, his lovestruck paean to Rachel, the beautiful drag queen who was his mid-1970s companion).

He embraced glam rock, a genre he’d done a great deal to invent, but the career-rescuing success of the David Bowie and Mick Ronson-produced Transformer was undercut by the unmistakable sense that Reed felt that glam was beneath him.

In the middle of 1974's Sally Can't Dance, an album he described as "a piece of shit" which he "slept through", he dumped Kill Your Sons, as nakedly confessional and personal a song as he ever wrote, detailing a psychiatrist’s attempts to cure the 17-year-old Reed of his homosexual urges and mood swings through electroshock treatments.

Charged with making a more straightforward album to appease his new label, Arista, whose intervention had apparently saved him from bankruptcy, he made Rock and Roll Heart, which, if it was pallid enough to get on mid-1970s radio, spoiled its chances of doing so with its lyrics: "I believe in the iron cross."

From the late 1980s onwards he could have settled comfortably into the role of beloved elder statesman of rock that the scale of his influence and importance warranted. New York, from 1989, and the following year's Songs for Drella, an astonishing album-length eulogy to Andy Warhol that rekindled his partnership with Cale, suggested he might –but it didn’t work out like that.

He seemed no more at ease with the elder statesman role than he had been as a make-up-caked glam star. He effectively scuppered a Velvet Underground reunion before they could make an album, which, depending on your perspective, was a squandered opportunity, or just as well.

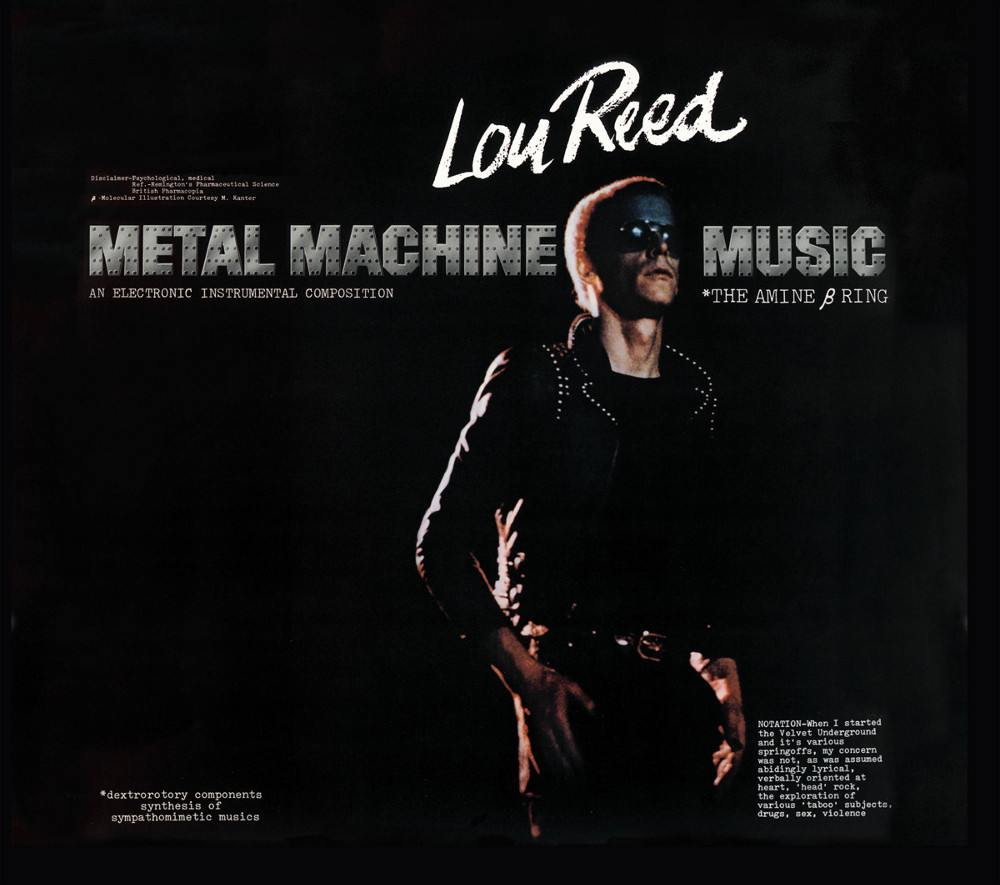

His shpilkes were clearly still raging, which explained how he could follow an album as good as Ecstasy with the scenery-chewing The Raven and his curious attitude to his own back-catalogue during concerts. He kept moving. You could never have accused him of cravenly coasting on past glories. Other artists performed their best-loved albums in their entirety live. Reed did an ear-splitting improvisation based on 1975's notorious Metal Machine Music and exorcised the commercial failure of his 1973 concept album, Berlin: a nostalgic evening of speed addiction, spousal abuse, screaming children and suicide.

It might have made a more satisfying end to the story if his final album hadn’t been Lulu, a collaboration with Metallica that Reed claimed was the best thing he’d ever done, but which received some of the worst reviews of his career. But then, Reed didn’t deal in happy endings, and instead he went out with one final, confounding, antagonistic act of perversity. He ended his life as unknowable and contrary as the 22-year-old who made Do the Ostrich.

In one of his last interviews – still on the news stands when he died – a journalist ventured to ask him why he didn’t write an autobiography. “Why would I?” he snapped. “Write about myself? I don’t think so. Set what record straight? There’s not a record to keep straight.”

And then he came up with a flat rejection of any attempt to make sense of a 55-year recording career that had transformed rock, and a line that could stand as his epitaph: "I am what I am, it is what it is. And," he added, "fuck you." –

© Guardian News & Media 2013