The wedding that caused all the trouble: The plane carrying guests from India for the lavish wedding of the Guptas' niece Vega at Sun City landed at Waterkloof Air Force Base.

“The Guptas?”

The Indian journalist blinked a few times before turning to his colleague in their Mumbai newsroom.

“Guptas? Kohn hai Guptas?”

Then came that head waggle peculiar to the subcontinent: half nod, half shake, as if the waggler was afraid to offend by saying no.

“Sahara?” I tried again.

“Sahara? You mean the Sahara Group?”

But no, I did not mean the $23-billion Indian superconglomerate, with interests in businesses ranging from movies and motor racing to manufacturing and finance. I meant its doppelganger – started in South Africa by a middling business family that left India in 1993 – ostensibly named after the Guptas’ home town of Saharanpur in the state of Uttar Pradesh in northern India.

It was 2010, and by then the Guptas had managed to trade off the Sahara name and achieve an astonishing level of influence in South Africa in less than a decade.

I happened to be in India reporting on festivities around the 150th anniversary of the first arrival of migrant Indians in South Africa, but a series of news breaks about the Guptas was making more news back home in South Africa – most notably about a mining deal involving them and Duduzane Zuma, one of President Jacob Zuma’s sons.

I decided to ask around to see what I could find out about them while I was in India. But the most I ever got was that head waggle. In the end, the only thing that was clear was that whoever the Guptas had become in South Africa was a far cry from what they had been in India.

“Few [Indian industrialists] would have heard of the Gupta family or thought of them as major players,” South African businessperson and commentator Kalim Rajab wrote on the Daily Maverick website earlier this year. “Before arriving in South Africa, they had been a middleweight family in the power stakes on the subcontinent … Rumours, never proven [but then few such things ever are in Indian courts] swirled around of them providing money-laundering facilities in Dubai.”

Institutionalised corruption

In India institutionalised corruption is par for the course. But in South Africa the Guptas have become an unlikely story of political patronage and rising influence since the first brother arrived in 1993.

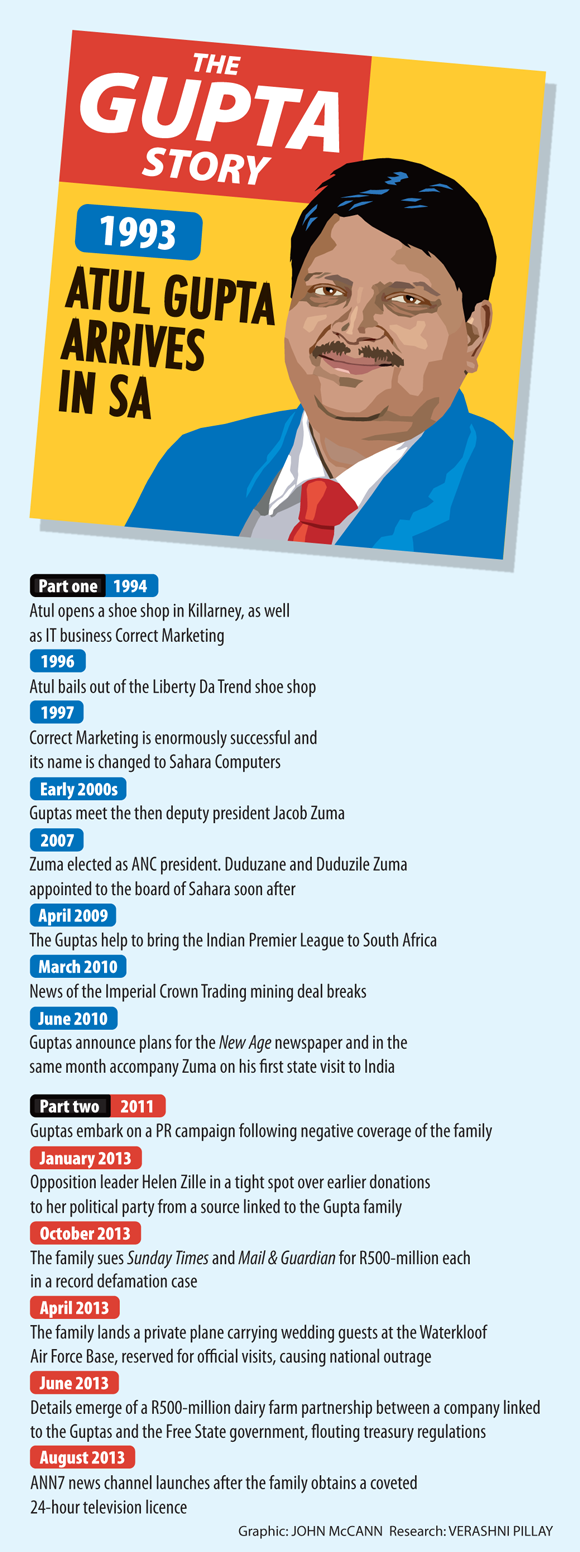

For the first five years or so after the Gupta brothers – Atul, Ajay and Rajesh – arrived in South Africa there was not a whisper about them in the news. Atul, the middle brother and public face of the trio, slipped quietly into South Africa’s nascent democracy in 1993: good timing ahead of the black economic empowerment boom for certain politically connected individuals. His older brother and the company’s business leader, Ajay, started visiting from 1995 onwards and settled here permanently in 2005. The youngest, Rajesh, who would become Duduzane Zuma’s friend and business partner, joined them in 1997. Their sister, Achla, and beloved matriarch, Angoori, completed the family’s set-up in Johannesburg.

Atul was initially sent to South Africa by his father, Shiv Kumar, who believed “Africa would become the America of the world”, according to a generous family profile in the Sunday Times in 2011, which the Guptas offered to the Mail & Guardian as a list of facts for this feature instead of having to answer questions. (In fact, several questions put to the Guptas by the M&G for fact-checking and in response to various allegations were left unanswered.)

At first Atul tried his luck with a shoe store in Killarney Mall in Johannesburg in 1994, the first of what he hoped would be a chain. But by 1996 he had closed the ailing Liberty Da Trend boutique. Another company, however, Correct Marketing, which was also started in 1994, was doing better. The computer and related components business changed its name to Sahara in 1997, and in the same year its turn-over rocketed to about R97-million from a mere R1.4-million in 1994.

The contrast between the life the tight-knit Hindu family had in Saharanpur and their local bling lifestyle is stark: their father, after all, was a humble store owner who worked his way up, leading to the brothers sometimes being referred to unkindly as nouveau riche by their more moneyed Indian counterparts.

For the next few years the brothers continued to build Sahara Holdings and its various businesses, including Shiva Uranium and JIC mining services, and kept out of the public eye.

But they were busy.

India’s business and government dealings are largely driven by a kind of institutionalised nepotism. Perhaps it was this culture that drove the Guptas to cosy up to those in power, particularly in the ruling ANC according to various reports, starting as early as former president Thabo Mbeki’s term in office. But the calculating Mbeki was said to have kept the connection very discreet.

Brothers

His successor, however, was less restrained. Atul told the Sunday Times that the brothers met Zuma “around 2002, 2003 when he was the guest at one of Sahara’s annual functions”. The family’s spokesperson, Gary Naidoo, put the time of the meeting as sometime in 2001 in a different interview.

At the time, Zuma, then deputy president, was a man to watch. But by 2003 trouble had started to brew, and a year later he would become embroiled with his financial adviser, Schabir Shaik, in corruption charges related to the multibillion-rand arms deal. The revelations at Shaik’s trial led to Zuma being ousted as deputy president by Mbeki, only to make a comeback in 2008 as ANC president.

One of the the Guptas’ bets had paid off. It is believed to be one of many, given the broad reach of their financial contributions. Even the opposition Democratic Alliance under the leadership of Helen Zille had to go to great lengths earlier this year to explain donations worth R400 000 from an associate of the Gupta family and one of its companies.

After years of relative obscurity in South Africa the Gupta family first started appearing in local news reports in 2009. But it was only in 2010 that they became notorious household names. This was mostly thanks to a dubious potential iron-ore mining deal that saw shelf company ICT, later linked to the family and others, nearly appropriate part of the mining rights to one of the world’s biggest opencast iron ore mines from under the noses of mining giant Arcelor-Mittal, thanks to alleged government intervention on their behalf.

Suddenly everyone noticed the Guptas were rather good friends with our president – and a number of other influential government ministers besides, including Malusi Gigaba and Naledi Pandor, who have stuck by the family during their most difficult moments.

Then, in June 2010, the Guptas accompanied Zuma on his first state visit to India, an important trade meeting intended to entice investment in the country.

The Guptas appeared to have acted as gatekeepers for Zuma on the trip. At one banquet, according to Rajab, Zuma made it clear that interested investors had to go through the Guptas, prompting several high-powered businessmen to leave in disgust. “It was clear that the family wanted to use Zuma to establish connections for themselves,” one businessperson told the M&G at the time.

Said another source: “They entirely grew in South Africa; they did not have much to speak of in India. This trip could have helped them gain access to people in India, which could not have happened otherwise.”

Surprise investment

Their growing influence culminated in a surprise investment by India’s largest media group, Bennett, Coleman & Company Limited. The usually risk-averse group helped to start the Gupta’s then most controversial project to date: their New Age newspaper in June 2010, in what might have been an answer to the grumbling from their politician friends about negative press coverage.

From the get-go the paper was plagued by staffing issues and publication delays. The first editor, Vuyo Mvoko, left before the paper had even launched and the second editor, Henry Jeffreys, left after barely six months. Jeffreys was followed by Ryland Fisher, who was replaced in August 2012 by Moegsien Williams, the former editor-in-chief of Independent Newspapers Gauteng.

Several former staff members related stories to the M&G about the unpleasant and draconian working conditions at the paper.

“Journalists were often discouraged from out-of-town trips with the reason being that these tend to be expensive,” one said. “This is despite the paper supposing to have a nationwide reach in terms of content and target market.”

The former staff members told the M&G they were submitted to something of an authoritarian regime, with written warnings for minor offences such as being late for work or using the company internet for nonwork-related purposes – even if it was a first-time offence. One former senior editorial staff member said seasoned journalists found their editorial decisions under constant scrutiny by the Guptas.

The New Age editorial processes slowly stabilised with time though its circulation is believed to be very poor. The paper’s circulation has never been audited, despite the family using every connection to encourage distribution for the widely perceived pro-government publication; at the ANC’s NGC conference in Durban in 2010, stacks of the papers billowed across the streets and, as alleged by complaining SABC employees, were forced in large quantities on the staff at the public broadcaster.

This didn’t stop government departments and parastatals such as Eskom and Telkom from in effect funding the paper with large adverts or from hosting business breakfasts for the paper. Often these events featured rare interviews with Zuma himself.

Growing empire

Meanwhile, the family’s Sahara Holdings empire grew to include mining, aviation and technology.

And their influence in India too continued to grow thanks to their South African successes. They were instrumental in bringing the Indian Premier League (IPL) cricket cup to South Africa in 2009 amid security concerns about holding it in India at that time. Soon after their 2010 India trip with Zuma they began playing a key role in Indian diplomatic circles in the country.

“It’s an open secret in the Indian expat community that a visiting Indian minister doesn’t get debriefed by the Indian high commissioner as is protocol,” said one insider close to the diplomatic community. “Instead they head straight to Saxonwold to get debriefed. The Guptas have become the de facto Indian diplomatic force in the country.”

By then the president, several ministers and a host of Indian luminaries had become regular fixtures at the family’s massive compound in the wealthy suburb of Saxonwold, Johannesburg, which includes four adjacent mansions for the four siblings, their spouses, mother and eight children.

The compound itself features a cricket pitch where the likes of Bollywood superstar Shahrukh Khan, together with his son, Aryan, played cricket with the Gupta children. The Guptas count legendary Indian cricketer Sachin Tendulkar among their friends, as well as Bollywood actor Anil Kapoor of Slumdog Millionaire fame. It was also reported that the family had a helicopter, three aircraft, nine pilots and five personal chefs.

“The extent of how much the Gupta family controls you, and by implication this country, has not even begun to be understood,” wrote former ANC loyalist and flamboyant businessperson Kenny Kunene in an open letter to Zuma this year, echoing a growing sentiment among South Africans and some in the party over the years.

The family were taken aback by negative media reports. Atul spoke about the teasing the family’s children had to endure at their school.

The family first responded with something of a PR drive, granting tightly controlled interviews such as the glossy feature in the Sunday Times in 2011. When the tide of negativity continued, the Guptas resorted to a sullen silence, then sued both the M&G and the Sunday Times.

I happened to be one of the journalists on the receiving end of the Guptas’ charm offensive. But resisting their advances resulted in, in effect, being blacklisted. The family refused to answer questions for this article, claiming I had published details of off-the-record conversations between us: a serious allegation that they never proved. Their only offer in terms of a response was to vet the finished version of this article (a proposition firmly against the M&G‘s editorial policy).

No wrong

It was a common refrain from the family: prove to us what we have done wrong. Show us the government contracts and tenders we benefited from, they would demand.

But it wasn’t as simple as that. The fact that Zuma’s family members – his children and fiancé – landed top positions at the Guptas’ businesses soon after he was elected did not translate into anything as obvious as a government contract. Instead the influence was insidious and more lucrative. Pricey business breakfasts sponsored by government and parastatals received extensive airtime on the national broadcaster. There were allegations of bureaucratic short cuts to help their businesses and regular stories alleging that officials had been leaned on to oblige the wishes of the powerful family.

That the brothers have a different way of conducting business became clear in other ways.

They appeared to have developed a habit of playing fast and loose with the country’s laws, and then relying on their political connections to smooth the way. In 2009 Indian newspapers reported that the co-owners of the IPL cricket team Kings XI Punjab, Ness Wadia and Mohit Burman, were beaten up by the family’s private security staff – and the police, according to some reports – for bothering a woman who turned out to be a daughter-in-law in the family. The Star, after receiving numerous complaints from local residents, ran a photo of the Gupta helicopter in Zoo Lake park, which is not far from their home. They would often be seen, according to Rajab and other sources, with police escorts despite having no official status. Even the zoning of their massive four-stand property in Saxonwold became suspect after it was discovered that the municipality – mistakenly or not – had underevaluated the plot, meaning the family paid a fraction of the rates they should have.

The family’s casual attitude towards red tape culminated in the Guptagate wedding scandal in April this year when officials at the Waterkloof Air Force Base granted irregular clearance to Jet Airways charter flight JAI 9900 from India. The 217 passengers were then ferried either by light aircraft, helicopters or in police-escorted vehicles to attend the lavish wedding of Vega Gupta – a niece of the Guptas – and Aakash Jahajgarhia at Sun City’s Palace of the Lost City.

It has been difficult to pin down exactly how the Guptas used and abused their political connections to date, but there was no getting out of this one. They bypassed South Africa’s laws and compromised its security, allegedly with just the mere mention of their good friend Zuma’s name. And as if the intolerable couldn’t get worse, some of their guests from India were reported to be racist to black staff at Sun City.

“[A] Gupta security [officer] told waiters … [to use towels, toothbrushes and toothpaste before they served guests],” Koki Khojane, a resort employee, told City Press at the time. The Guptas denied the allegations, with Atul telling Business Day that the family was “unaware of the incident”, adding that they “take matters of this nature very seriously”.

Still, the fallout from the scandal was so huge that many of the family’s friends in politics – including Zuma himself – stayed away from the nuptials.

“I think they should have just landed at Lanseria,” a senior ANC leader who is usually fiercely supportive of the family confided to the M&G for this article.

Linked company

Instead of being frozen out, though, it seems it has been business as usual. In June this year the M&G revealed a R500-million dairy partnership between the Free State government and a company linked to the Gupta family, which appeared to thumb its nose at treasury rules drawn up to stop private interests from abusing public money. But the family denied involvement in the project.

Not long after this, the Guptas had set their sights on their next media project: ANN7, a 24-hour news channel, also involving Duduzane Zuma. After being awarded a coveted broadcast licence, they launched to much derision, with on-air bloopers and blapses that quickly went viral.

But serious news made the headlines: this time the most dire account yet of the strained conditions of working under the Guptas. ANN7 consulting editor Rajesh Sundaram, who had been brought in from India, resigned about a week after the channel launched and returned home, citing pro-ANC editorial interference in his work, bad treatment of staff and 16- to 18-hour working days. In a jarring interview with City Press soon after he left, Sundaram described the working life at ANN7. “Mr [Atul] Gupta sits on the mezzanine level. There is a glass wall there and he stares into the newsroom, looking at how many minutes any person has spent in the toilets or the cafeteria. There is a constant scrutiny.

“One time [Atul] went into the gallery because the news bulletin had been delayed by two minutes, shouting: ‘You monkeys! F*****g get out of here, pack your bags and go back to India!'” Sundaram claimed he was subsequently threatened and had some of his possessions stolen by people linked to the Guptas (though there appears to be no proof of this). He says he fled the country in fear for his life. At the time, the station’s group chief executive, Nazeem Howa, dismissed all of Sundaram’s claims as “not worthy of a response”.

It has been three years since I first enquired after the Guptas in their home country. They’re bigger fry in India now thanks to South Africa, and Indian journalists are probably less likely to waggle their heads when asked whether they know of them.

Back home, they keep astutely climbing the political, social and economic ladders. But what a price they have made us pay for the privilege.