Horse power: A cart speeds past a roadblock on day three of Operation Marikana on the Cape Flats. Photo: David Harrison

I am not anxious when my boots touch the pavement outside the Philippi metro police station in Cape Town’s Cape Flats region. But I cannot deny the sudden increase in my pulse rate. A brisk wind forces my hands into my pockets — which is also an attempt to look relaxed, playing it cool, as if I have done this before.

I’m escorted to the officer I was told to meet, to facilitate my witnessing Operation Marikana first hand.

“Morning director, thanks for having me.”

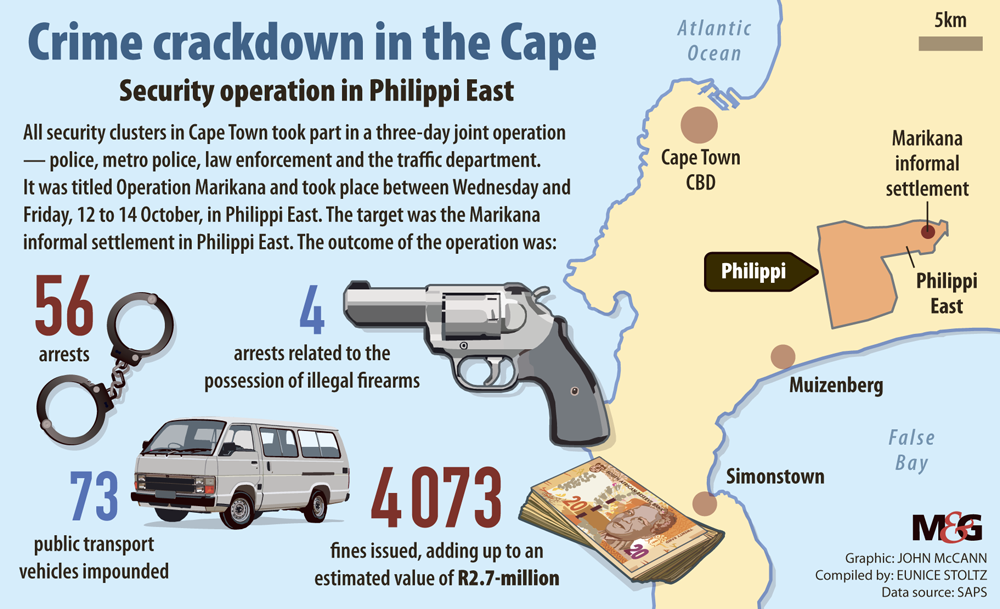

About 750 officers from the South African Police Service as well as Cape Town’s metro police, traffic services and law enforcement division are preparing for the third and final day of Operation Marikana.

Marikana is an informal settlement in Philippi-East where housing is inadequate, the delivery of basic services is below par and work opportunities are minimal. The area, 20km away from the city, is a hotspot for extortion rackets and carjackings.

Philippi-East is on the top 10 list of police stations with the highest number of murders in the Western Cape. More than 520 were reported in the township from 2018 to 2021.

Operation Marikana is the result of residents’ outcry against crime during a public meeting with the local government. The joint operation was planned little more than a month ago, and officers were warned about long working hours a week before it started.

I’m assigned to a superintendent who I will tag along with for the day. After signing an indemnity form, I’m handed a bulletproof vest and informed: “When you are told to duck, you duck. When you are told to run, you run.”

I nod my head and utter “sure”, trying to hide a rush of adrenaline. I secure the bulletproof vest and place my pencil and notebook in its pockets. On the outside I keep my cool, but inside I feel a bit like a war correspondent.

The atmosphere in the vast parking area where the officers are gathered in groups for their daily briefing is weirdly cheerful. It seems to me the laughter and light conversational tones ahead of the task ahead might be a coping mechanism for the officers who face danger every day.

Statistically, several areas on the Cape Flats can be considered war zones; many people are killed in gang battles and taxi violence. Over four days, from Friday 14 October to Monday 17 October, 11 people were killed in the red zone suburb of Hanover Park, not far from the Marikana settlement.

On the outskirts of Marikana, the superintendent parks in front of an unmarked police vehicle.

“Dit is maar ’n rowwe area, hier is min polisiëring [this is a rough area with limited policing],” she says, looking at the informal shelters surrounded by a near-impassable road.

Ahead a large group of officers is getting ready to carry out foot patrols in search of firearms and drugs.

I’m introduced to the regional inspector for the city’s law enforcement division. He says the majority of residents welcome the officers’ presence. The taxi drivers, on the other hand, show the contrary.

Our first stop is brief.

Back in the vehicle, the superintendent gives orders through her two-way radio.

In the distance, a helicopter, which is providing aerial support for the operation, can be heard. Incoming calls for the superintendent on her handheld radio and cellphone drown out the sound of the aircraft.

Officers may be part of this operation, but they still carry out their day-to-day work. Forces are needed in Uitsig where a gang fight has erupted. The superintendent orders law enforcement officers to join the anti-gang unit in that area.

In Belhar, a woman has been shot dead in front of her son on their way to school. Officers are dispatched to the scene.

Pulling me back to the Marikana Operation, the superintendent announces they have found a firearm.

Eight law enforcement vehicles pass us as they speed to Lower Crossroads. Residents say the area is a place police seldom visit.

Two officers on horseback ride by to maintain police visibility in the area.

The superintendent says Operation Marikana was planned diligently. The officers will be stationed at specific locations — such as drug houses and convenience stores — to “cover all the hotspots”.

Multiple vehicle control points have been set up in main roads entering and leaving Philippi-East.

The side roads are also strategically cordoned off to prevent criminals from escaping the control points. At one point a taxi driver takes a right turn to try to evade the blockade — only to be brought to a standstill at another.

“Now we pin them on that side,” says a traffic officer.

At another vehicle control point the superintendent tells me she is the commander of a tactical response unit of 30 officers using an armoured personnel carrier, the Nyala, or what she calls “The Beast”.

Forming part of the four specialised K9, equestrian, anti-gang and tactical response units, the Nyala is there when incidents turn violent.

A metro police officer approaches me as I take photographs of a Nyala parked near a control point. He is part of the superintendent’s team. He explains that the vehicles bring in the protection. A Nyala can withstand many forces, including a grenade explosion. It can reach a speed of 95km/h and has been a “saviour in many sticky situations”, says the officer.

Blitz: A man is arrested and Cape Town safety and security representative JP Smith (left) inspects a vehicle engine during Operation Marikana. Photos: David Harrison

Despite the many risks, he enjoys coming to work.

I ask him what a successful day at work looks like. Scenes of raids, dodging bullets and speeding across a red traffic light as motorists stop at the sound of sirens, flash through my mind.

His answer brings me back to reality. “A successful day is going home alive.”

The superintendent asks if I have ever been in a Nyala. Responding to my “no” she says: “Let’s get you in one.”

From where I sit (in the very front seat) I can see people’s reaction to The Beast. It is a mixture of fear and curiosity. The Nyala represents law, order and the enforcement of it.

We make one search-and-go stop in which three people are searched for firearms and drugs.

We continue through the narrow streets. This time I climb into the back of the vehicle. The officers are focused on their surroundings, paying attention to any suspicious activity.

As I grab a pole as we make a turn, I realise the “pole” is a gun. I’m too embarrassed to ask what type of gun it is, but it is a very long one.

My Nyala trip ends and I’m soon joined by the city’s mayoral committee member for safety and security, JP Smith, and the metro police station director.

On the second day of the operation, taxi drivers intercepted Smith, demanding that he not impound their vehicles. The final day is no different. Officers issue 1 664 traffic fines totalling about R1-million and impound 19 vehicles.

Smith is approached by taxi operators and spends a long time listening to them.

As the discussions continue, some operators try to talk to their colleagues who are locked in the back of a police van.

“We will be back,” Smith tells the taxi operators.

Eleven motorists are arrested for outstanding warrants and one for a fraudulent driving licence.

In one incident, I see a driving instructor being arrested after being caught giving driving lessons without being in possession of a driving licence.

But it is crimes such as extortion, carjacking and gender-based violence that strip people of their freedom.

Smith says crime figures in the area are “off the charts”.

Every business in the area gets extorted. Every house gets taxed by extortionists.

Although crime prevention events such as Operation Marikana help ensure that law and order are enforced, I cannot help but wonder when the underworld syndicates driving illegal criminal networks will be traced and arrested through good intelligence.

Smith says they have “hit the rhythm” for joint operations with the South African Police Service (SAPS).

He tells me about the “solid relationship” between “Cape Town’s law enforcement and metro divisions and SAPS”.

He adds: “I think it is very hard” and then says, “Patekile is a star. He is all work, no politics.” Lieutenant General Thembisile Patekile is the Western Cape police commissioner.

Later, at a spaza shop in the heart of Lower Crossroads, two suspects are arrested.

Inside the store, one person lies on his side, his legs visible from the entrance. Another suspect is handcuffed by a police officer.

A search of the store leads to the discovery of illegal ammunition.

Outside, a police officer notes how spaza shops are a major problem because they are usually run by foreigners, making them a soft target for extortion.

Dozens of residents fill a narrow street. Children gather on the pavement, wanting to know more about what is going on.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

I speak to young women peeping curiously around a street corner. They welcome the presence of the police, they say, but ask where they can get a job.

Another onlooker, a woman returning from work, snorts: “I’m surprised. It is the first time I see police here. When you need them, they are not around.”

As I find my way to the superintendent waiting to take us back to the metro police station, I see the faces of children, teenagers and adults, who are exposed to constant violence in similar places across South Africa.

[/membership]