Black cctv outside the building, home security system. Photo: Getty Images

A witness protection programme might sound like a movie featuring Liam Neeson or Keanu Reeves, packed with adrenaline, undercover operations, weapons and safe houses.

In reality, South Africa’s programme is a life of sacrifice for the witness and the protector.

“I want to get a gun,” says Allen*, a state witness who fears being discharged from the programme, which is run by the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA).

He lives in a bachelor flat about 700 km away from his family, the result of being in witness protection.

Once a husband, father and farmer with a stable income, Allen’s life was irrevocably altered when he witnessed the assassination of a close relative and had to appear for the state in the subsequent court case. As a result of his testimony, he received threats to his life, leading to the application to enter witness protection.

Now, three years later, Allen is being discharged from the programme, but he refuses to leave, believing his life is still in danger.

Allen’s son was gunned down at the beginning of this year and several of his cattle have been slaughtered by people he says are after him.

He was told in September that he would be discharged from the programme last month. He asked his overseeing officers for an extension to at least January. He also asked to be moved to another province, with his family. His requests have not yet been approved.

With many of his expenses paid — rent, water, electricity — Allen pays for groceries and sends money to his family. However, he is no longer receiving his monthly state payment of R15 000 because his period of protection has expired. He will go home unemployed and fearing for his life.

He says the programme did not prepare him for reintegration into society and his overseeing officers had not conducted a risk assessment.

Not all people who apply for protection get in.

In an unrelated case, a woman who accidentally witnessed a gang attack agreed to testify for the state.

She claims she was declined police protection, while having to testify in court, and was only considered for such when her family home was hit by a hail of bullets.

“When you testify, they drive you to and from court; they do not have food money — you must sort yourself out. Once you are done testifying, they do not want anything from you anymore …. You are not valued by the state, no matter if you are giving up your life.”

At the time of the shooting incident about four years ago, a nonprofit organisation that helps victims of organised crime arranged private funds to relocate the woman and

her family. According to the witness, the organisation continues to support her and her family.

The organisation — which is known to the Mail & Guardian — declined to comment.

The NPA has reserved its right to comment. Elaine Zungu, director of public prosecutions, said “the information requested is sensitive and delicate in nature as it pertains to witness protection. We therefore reserve our right to comment.”

On the NPA’s website about the Office for Witness Protection, it states: “The OWP manages the safety of witnesses and their immediate family pre-, during and post-trial.”

Although the NPA administers the OWP, it is housed in the department of justice. Despite the general nature of the inquiry, spokesperson Chrispin Phiri also declined to comment because the department does “not comment on witnesses under the programme”.

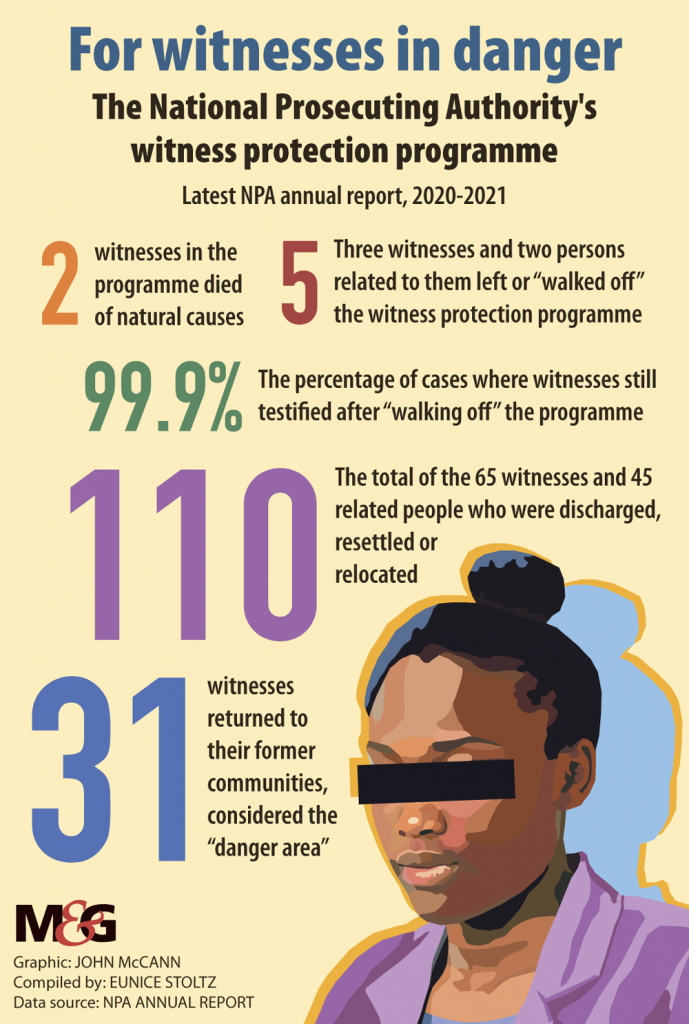

The NPA’s 2020-21 annual report sheds some light on the witness protection programme.

Last year, 45 “related persons” on the programme were “discharged, resettled or relocated through amicable resettlement agreements”.

“The OWP assists persons in the WPP (witness protection programme) to successfully reintegrate into society; however, due to budget constraints, aftercare, discharge and resettlement are limited.

“Despite this, there has still been a 100% successful resettlement,” reads the report.

“It is not like the movies,” laughs Estelle* a retired witness protection officer who agreed to speak to Mail & Guardian on condition of anonymity. She says there are different types of witnesses.

Some people’s lives are upended merely because they were in the wrong place at the wrong time. Others looked for trouble and eventually found it. On the flip side, there are people who actively participate in criminal activities and decide to turn state witness.

While speaking to the M&G, Estelle withheld sensitive information and details of her time as a witness protection officer.

She says she would often be woken by a phone call from her commander in the early hours of the morning, which led to a chain of events she had mastered by then. She would pack her bags, say goodbye to her husband and children, and set off to where she was needed, in some instances up to 1 400km away.

Dressed in casual wear, she would drive in an unmarked vehicle not registered under the state. She carried a gun in her handbag.

“You walk around without anyone knowing who you are or what you do,” Estelle says.

When a situation occurred that needed police intervention, but was separate from her job to protect a state witness, Estelle could not act because she could risk giving away her identity as a witness protection officer. The safety of the witness was her priority.

She remembers an incident when the perpetrators learned about their whereabouts while she was transporting a witness back from court. The perpetrators tracked their vehicle and unsuccessfully tried to push them off the road. Estelle got the witness to safety without being harmed.

“Most of the time witnesses are safe but there were incidents when a witness had to be relocated.”

According to the NPA’s 2008-09 annual report, no witnesses were harmed while on the programme between 2004 and 2009.

But the same report discloses that incidents of harm are not included in annual figures because “the programme intends to protect witnesses from outside threats or attacks”.

It further states: “A witness stabbed his wife to death and then committed suicide by hanging himself while on the programme. Another witness drowned at sea while swimming in Durban. A witness and her baby were injured while being transported.”

Estelle says that before witnesses’ permanent accommodation at a safe house or rental home is finalised, they are temporarily placed in guest houses and hotels.

Although the majority of her witnesses did not change their physical appearances, there were serious cases where top management would handle it, she recalls. She says some witnesses coloured their hair but added this was not mandatory.

Witnesses were not issued with new identity documents, “they just did not do any business further” and received a weekly allowance in cash.

It is not clear what type of scale is used to determine the weekly allowance for witnesses.

Estelle says in her day, witnesses received around R1 500 a week. According to Allen, he receives R15 000 a month.

A police confidant of Estelle, who is still in the service, confirmed the amount of R15 000 was limited to a few cases and that a smaller allowance, closer to R1 500, was the norm.

Without excluding the emotional strain on witnesses, Estelle describes the lives of people under protection as comfortable.

“They are very fortunate [and] they don’t always appreciate it. They have a very nice life.”

She says the homes of witnesses, who in some cases are joined by their family, are refurbished with new curtains, bedding and furniture.

“A lot of money is spent on them. Some people stay on the programme for years. It becomes a lifestyle.

“For many witnesses, the programme serves as an opportunity for a new life. You are offered a new beginning while being paid for it.”

The state does not offer witnesses the opportunity to study while on the programme but Estelle says, should a witness request it, the state would consider it.

She questioned if some of the evidence given by witnesses justified their being on the programme.

“My children and I were once threatened and we did not receive protection. So, you do not always know on what merit witnesses are approved or not,” Estelle says.

The 2009 report also indicates that 2.4% of the 218 witnesses laid formal grievances while on the programme. It does not elaborate on the type of grievances.

A highly confidential programme that is largely unknown to the public — for obvious reasons — carries the risk of being exploited.

Estelle says there are “loopholes” that witnesses and officers could abuse, with the most obvious being to invoice for nonexistent expenses.

The annual reports do not provide a summary of expenses or the budget of the witness protection programme. But in the 2009 annual report, a brief remark puts the expenses into perspective.

“A significant achievement of the unit is a saving of R3 004 896 that resulted from a decision to eliminate and reduce luxury and unnecessary accommodation allegedly used for operational purposes.”

In 2008, there were 218 witnesses in protection — a decrease from 247 in 2004 — of which 16.9% walked off, according to the 2009 annual report. Annual reports from recent years do not provide these specific details.

[/membership]