Disquiet: Law enforcement officers in Nyanga township on day five of the minibus taxi strike that has seen five people killed, vehicles burnt and public services brought to a halt. Photo: Jaco Marais/Gallo Images

The violent and deadly taxi strike in Cape Town has not only strangled the city’s economy and public movement, but has also exposed the national government’s apparent reluctance to take decisive action against the sector.

On Monday, the taxi strike, which has affected large parts of the Western Cape, prevented more than 280 000 learners from attending school, while public violence restricted health services and emergency responses and infrastructure was damaged. Five fatalities have been recorded.

Police Minister Bheki Cele remarked that the matter was a transport, not a policing issue. He spoke to the Mail & Guardian hours before publicly condemning the violence only after relative calm was restored in volatile areas.

Shortly before Cele’s address to the media on Tuesday afternoon, Transport Minister Sindisiwe Chikunga described the City of Cape Town as “arrogant”, further fuelling tensions between the city and taxi leaders.

President Cyril Ramaphosa’s office had not responded to the M&G’s questions sent on Monday regarding the ongoing taxi violence. Cape Town MEC for safety and security JP Smith, who has been criticised by the ANC for being a law unto himself, slammed Ramaphosa’s silence at the height of the taxi violence.

“They either see this as a political opportunity — the political points trump the reason and sensibility of it — or they do not understand the issues and they are therefore not willing to weigh in and have the vision to see what is at stake,” Smith said.

The South African National Taxi Council (Santaco) continued its strike on Thursday, extending it beyond the initial planned seven-day protest.

Western Cape Premier Alan Winde told the M&G on Wednesday evening, after meetings with Santaco yielded no results: “We want to be fair but we also want to be tough on crime, we want to be tough on safety, we want to be tough on the law.”

The premier’s office in the DA-led Western Cape took over discussions with Santaco and the national department of transport after negotiations between the taxi group and the City of Cape Town reached a stalemate last Sunday.

An entourage of armed bodyguards carrying assault rifles allegedly escorted Santaco leaders to the negotiations with city officials. Smith said Santaco abandoned the talks after its armed guards were searched by city law enforcement officials.

Disruption: Golden Arrow buses stop alongside the N2 at the entrance to Nyanga to take people to the city and other areas amid the ongoing taxi strike that has left workers and schoolchildren stranded. Photo: Brenton Geach/Gallo Images

Disruption: Golden Arrow buses stop alongside the N2 at the entrance to Nyanga to take people to the city and other areas amid the ongoing taxi strike that has left workers and schoolchildren stranded. Photo: Brenton Geach/Gallo Images

The city said it would not negotiate at gun point. “We’ve taken a principled position that we will not speak to those who are perpetrating violence until it stops,” Cape Town mayor Geordin Hill-Lewis told the media, while standing next to Cele.

“The fact is that the people that we are negotiating with in a conference room are the same people with members who are out in the streets causing incredible violence and mayhem in our city — and even murder.”

Cele, who has publicly defended his presence at a Santaco meeting last week, insisted to the M&G that the standoff between the city and Santaco did not involve criminality and that the solution “lies within the city”.

He said Santaco provincial chairperson Mandla Hermanus and Smith “just need to fix those matters, it is that simple”.

The prolonged taxi strike seems to stem from renewed tensions between leaders in the taxi industry and the provincial government. These arose when Santaco withdrew its participation from the minibus taxi task team — an initiative aimed at addressing permit barriers and other grievances in the Western Cape.

In a letter dated 9 August and seen by the M&G, Santaco told MEC for urban mobility Ricardo Mackenzie that it was not opposed to vehicles being impounded provided this fell under national legislation.

The taxi council also repeated its call for a moratorium on impounding vehicles “until such a time that we are able to resolve these issues”. Santaco said it “maintains its position to continue with the taxi stay-away until a moratorium has been instituted by the city and Western Cape government, pending the resolution of all outstanding matters at the minibus taxi task team”.

Santaco announced the strike last week over what it called the “frivolous impoundment operations run by the [provincial] government, which has had a negative impact on our operators and industry”.

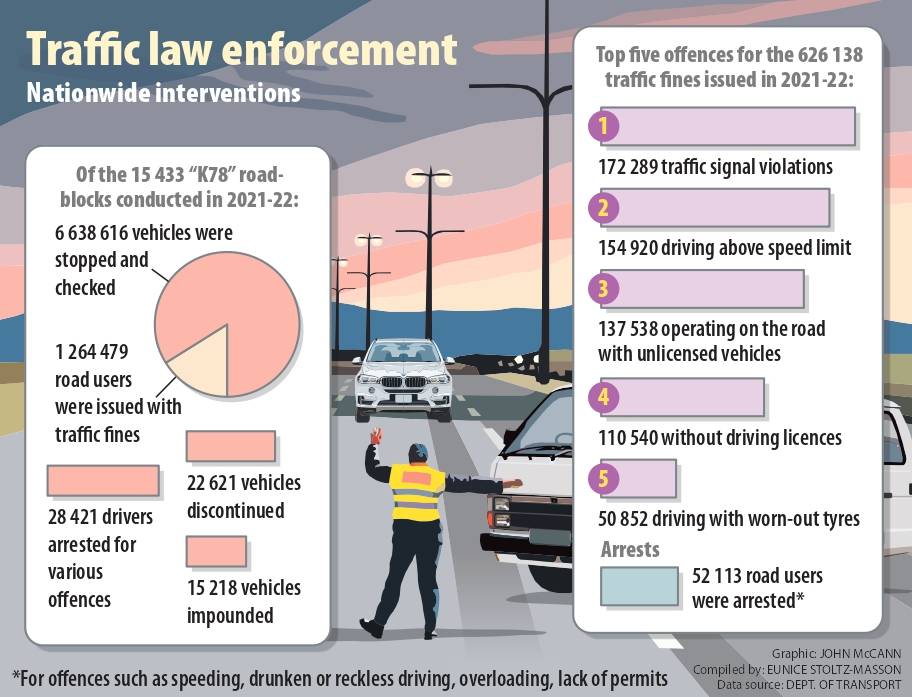

There has been a significant increase in traffic fines, arrests and vehicle impoundments affecting all motorists since Cape Town’s amended traffic by-laws came into effect in July.

The city’s weekly road statistics during the second last week of July show a combined figure of nearly 400 arrests carried out by local law enforcers, metro police and the South African Police Service for offences including driving under the influence and speeding.

More than 26 200 fines were issued for various traffic violations and a further 326 public transport vehicles were impounded, compared with 264 the week before and 248 during the first week of July.

“The vehicles are impounded in terms of legislation, where drivers are unable to produce a valid operating licence, or are found to be operating contrary to the conditions of their operating licence,” the city said in a statement.

During the past year, the city has impounded 6 245 minibus taxis, nearly 500 of which are stationed at its Maitland pound. An adjacent field is under construction to increase its holding capacity.

In other hotspots in the country where taxi violence frequently flares up, the numbers of impoundments, specifically of minibus taxis, are much lower than Cape Town.

In Gauteng, 299 taxis have been impounded since the start of the year, of which 17 are stationed at its pound in Benoni, the provincial traffic department confirmed. The traffic department in KwaZulu-Natal did not respond to an inquiry sent well in advance of publication. But the impoundment of 64 taxis in the province’s Ugu district in May 2022 was widely reported and welcomed by local authorities.

On Tuesday, Chikunga, to whom Cele deferred, lambasted the city for its drive to enforce traffic by-laws and clampdown on taxis which critics say are a peril to passengers and other road users.

After meeting Santaco and local government officials in the Western Cape, Chikunga called for the immediate release “without any conditions, all vehicles impounded based on operating licence and leave those impounded in terms of the National Land Transport Act of 2009”.

“We call on the City of Cape Town to respect and uphold national laws as they currently stand,” she told a media briefing.

Chikunga said the city’s by-laws were in contravention of national law and if the rest of the country were to impound vehicles on the same conditions, there would be no vehicles on South Africa’s roads.

(Graphic:John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic:John McCann/M&G)

“She is running away from the truth,” said Mzwakhe Nqavashe, chairperson of the city’s safety and security portfolio committee which passed the traffic by-laws.

“There is no by-law that is wrongly enforced. No taxi has been impounded under a by-law. She is misguided or she is deliberately mischievous to say that.”

There is a lengthy process preceding the promulgation and final enforcement of any by-law, said Nqavashe. The city’s by-laws are drafted by a portfolio committee whose members are drawn from the Economic Freedom Fighters, the Good party, Freedom Front Plus and other political organisations.

The by-laws are the product of a legislative process that started in 2016. Nqavashe said the amendments were motivated by the National Land Transportation Act, which was considered to only focus on minibus taxis.

A gap was identified in that national legislation applies exclusively to public transport, Nqavashe said, “so there was a need to change the behaviour of all motorists, not only public transport”. He stressed that outside legal opinion was obtained, including from Halton Cheadle, who helped to draft the Bill of Rights in 1996.

When the final draft of the by-laws was submitted for public comment, Nqavashe pointed out that the portfolio committee did not receive complaints from the taxi industry because, at the time, it “did not think [the by-laws] talks to them, because they have been covered in the [Transport Act]”.

A source who was directly involved in drafting the National Transport Act and spoke to the M&G on condition of anonymity, said the Act “does authorise the city to impound taxi vehicles when they act in contradiction to their operating conditions”.

The source, who continues to work on the Act and its amendment bills which are before parliament, argued: “All the laws are in place, they are just not being enforced.”

The chairperson of a taxi association affiliated to Santaco, who has been barred from operating on the Cape Flats while the strike continues, said the national government was to blame for the crisis.

Speaking on condition of anonymity, he said: “The government saw these things coming; [they] are responsible for this mess. They just kept on allowing taxis onto the road. They should have said ‘no permit, no vehicle’.

“They just need to impound all the vehicles that do not have permits, and take all the pirates off the road,” he added, pointing out that a permit application form states that the applicant cannot be part of any criminal activity, but “nobody, not even the government, take notice of the form”.

He said he and his drivers had no choice but to take part in the Santaco strike.

Santaco met the Western Cape government on Thursday to discuss a resolution. The taxi council also indicated that it was seeking legal advice on obtaining a court interdict for the release of all its impounded taxis.

The Golden Arrow Bus Services, which is contracted by the city to offer transport services in Cape Town, has not been able to operate a full service since the strike commenced last week.

“The company has suffered significant financial losses,” Golden Arrow spokesperson Bronwen Dyke-Beyer said.

“Our primary concern is trying to render a service to people who desperately need transport to provide for their families, to get to educational institutions and to access critical services such as health care.”

Golden Arrow and the City of Cape Town both obtained court interdicts against taxi members harming or intimidating bus drivers and passengers, or obstructing, interfering or blocking any vehicle or public roads.