Deadly: Tiffiney Carolisen (in red) leads a march in Delft after her sister, Aqeelah Schroeder, was killed in 2022. Photo: Brenton Geach/Gallo Images

Unrelenting gang rivalry in Delft, the murder capital of the Western Cape, reached a grim crescendo this month when the death toll in suspected gang-related shootings had, by Monday, reached 23, with five of the victims being children.

September has been a month of renewed bloodshed and gang fights across the township, where more than 20 gangs seek dominance over territory and the drug trade.

South Africa averages 68 murders a day, according to the latest quarterly crime statistics, but the recent murders in Delft heightened alarm bells when the five children under the age of 16 were murdered over a period of 10 days.

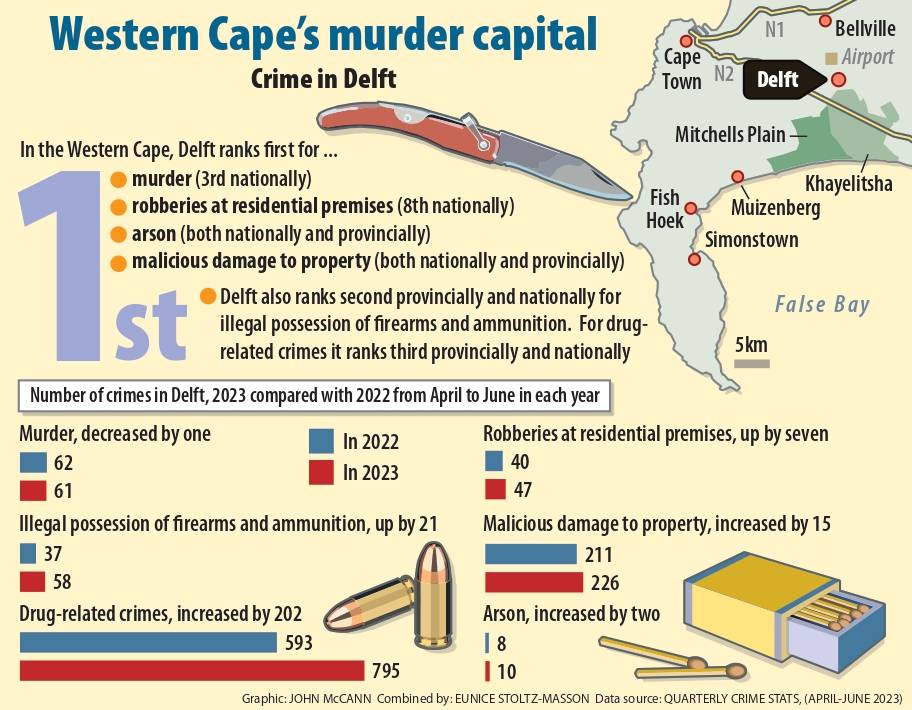

Delft recorded 61 deaths from April to June, according to crime statistics.

A resident who works closely with the police said the area is now experiencing “two, three to five deaths daily”.

In one incident, two boys were shot dead in what some residents believe was a case of mistaken identity.

The Mail & Guardian has confirmed that at least two of the five children were active gang members.

The resident, who spoke as long as he was not named, said the gangs are fighting over drug territory in schools and the recruitment of learners.

“The danger now is recruiting our youngsters in schools. Because they want them to be part of them [gangs] and sell drugs in schools.”

One of the boys who was killed was a learner at Delft High School.

The resident said the school is situated in the middle of the territory of about five gangs — the Terrible Josters, the Outlaws, SpongeBobs, Junior Mafias and the Bloodlines.

Another school, Rosendaal High, is sandwiched between the Hard Livings and Terrible Josters gangs.

Although there are crime prevention projects in schools, said the resident, difficulties come when school ends and learners have to walk home through the territories of rival gangs.

Schoolchildren face the danger of mistaken identity, said the resident. For example, “they are SpongeBobs but stay in Outlaw territory and are then killed for being an Outlaw, while not being part of the gang”.

A grade 11 learner at Rosendaal High admitted to sometimes being scared “because you never know what can happen, like maybe gangsters can come [into] the school while you [are] busy working”.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

The pupil also said that gang activities can “ruin your future by interrupting you while you [are] busy learning”.

The pupil said joining gangs was about status. Another grade 11 learner said that other reasons for joining gangs included needing to be noticed or “just for fun”.

Situated on the outskirts of Cape Town next to Cape Town International Airport, Delft is home to a growing population of impoverished and unemployed people who are highly susceptible to gang influence.

“Drug lords are contributing to the community, the people are facing a lot of challenges and the drug lords help fill that void,” said Reginald Maart, a member of the Delft community policing forum (CPF).

The MEC for police oversight and community safety, Reagen Allen, said his department “recognises that the challenge in addressing criminal gangs in the province is complex” and requires an “holistic approach which extends beyond law enforcement”.

Aside from coordinating a strategic and transversal anti-gang plan in partnership with the police, Allen said his department was reviewing interventions that aim to address the gang phenomenon in the province.

“The department’s main aim is to refine and strengthen existing interventions which present promising evidence of [their] impact, to reduce gang membership and violence,” he said.

The department of social development in the Western Cape spearheads crime prevention programmes together with child and youth care centres, said the department’s spokesperson, Ananda Nel.

The programmes involve services to “youth at risk”, which includes gangsterism. Moreover, the department’s youth development programme specifically focuses on the holistic development of young people who are unemployed or not receiving education and training.

These training programmes are facilitated at “youth cafés” that are operated by nonprofit organisations in places such as Mitchells Plain, Vrygrond, Crossroads and Nyanga in Cape Town, as well as in the towns of George, Uniondale, Oudtshoorn, Hessequa, Great Brak River, Saldanha, Velddrif and Villiersdorp.

The programmes have grown to 14 566 participants, up from 12 615 in 2021-22.

But some places are “no-go areas” for development workers because of crime, said Nel.

“Due to violence, certain programmes are terminated and young people miss out on opportunities,” she added.

Gangs also control entry into some places.

“Young people are prevented from attending youth cafés,” said Nel, because “youth and parents are afraid to move due to territorial gang fights and shooting”.

The police described the recent surge in murders in Delft as “sporadic incidents with no definite pattern”, said Western Cape police spokesperson Lieutenant Colonel Malcolm Pojie.

He said the police “remain concerned about the prevalence of violent crime, more specifically murders in the Delft policing area of which the majority is regarded as gang-related”.

Integrated deployments, supplemented by high-density patrols involving the police service’s specialised units and local law enforcement entities and counterparts, such as traffic and officers attached to the Law Enforcement Advancement Plan (LEAP), were initiated on an ongoing basis, said Pojie.

Ian Cameron, the director of civil rights lobby group Action Society, lashed out at Police Minister Bheki Cele on 13 September, when the murder rate in Delft was at 16.

“Bheki Cele is missing in action while the Delft community is bleeding uncontrolled,” Cameron said in a statement.

He told the M&G that “there is just no control from the state’s side”.

“The gangs — especially the Terrible Josters — are currently so strong that the community cannot speak out, because if you talk they shoot you dead.”

Cameron recalled the words of a neighbourhood watch member who described their daily patrols in Delft as a “suicide mission”.

A recent ruling in the Western Cape high court supports Cameron’s claim that residents are afraid to testify against gangs.

In July, the court granted the state’s request for a witness to testify on closed-circuit television and not to be named, in a matter that involved Elton Lenting, the alleged gang leader of the Terrible Josters.

Lenting and 19 other people are facing charges of murder, attempted murder, illegal possession of firearms, unlawful possession of ammunition, drug possession, drug trafficking, kidnapping, assault, arson and theft.

Additional LEAP officers were deployed to Delft on 17 July to increase the “boots on the ground,” said Allen.

“The unit currently consists of 73 members and together with the existing deployment, increases the total members deployed in Delft to 144 members.

“We also have 28 neighbourhood watch accredited structures in the Delft area comprising 428 members.”

Allen commended neighbourhood watch members, saying they were a “critical cog in our efforts to combat gangsterism and crime in general” in the area.