Nasa, famous for its missions into space, has set its sights on close encounters of a different kind — the Greater Cape Floristic Region at the south-western edge of South Africa.

Nasa, famous for its missions into space, has set its sights on close encounters of a different kind — the Greater Cape Floristic Region at the south-western edge of South Africa.

Since last month, its aircraft and instrument teams have taken to the skies to do aerial surveys as part of a pioneering research project to study the biodiversity of one of Earth’s six floral kingdoms and its surrounding coastal and marine ecosystems.

The Biodiversity Survey of the Cape (BioSCape) is an international collaboration between Nasa and several organisations in South Africa. It uses remote sensing and field data to understand the distribution, function and importance of biodiversity in the Greater Cape Floristic Region, which is home to thousands of plant species found nowhere else on the planet.

The region contains two biodiversity hotspots with the richest temperate flora and the third highest marine endemism in the world.

The project, which was initiated in 2021, will run until next year with most of the data collection occurring from mid-October to mid-December this year. The campaign will link data collected by satellite and Nasa aircraft with field observations of the region’s biodiversity on land and in the water.

BioSCape is a combination of airborne remote sensing and extensive fieldwork, said Jasper Slingsby, the South African lead scientist and a senior lecturer in plant ecology and global change biology at the University of Cape Town.

The fieldwork spans vegetation surveys, measurement of plant traits such as leaf spectral signatures and physicochemical properties; acoustic recordings of birds and frogs; collection of water samples to extract environmental DNA and more, Slingsby explained.

“BioSCape is a unique and exciting project that will help reveal new insights about the biodiversity of one of the most diverse regions on Earth and provide new tools for mapping and monitoring it,” he added.

This information will be essential for supporting effective biodiversity conservation and management strategies for the region.

“BioSCape will also benefit the world by improving our understanding of biodiversity and facilitate the development of new technologies to monitor and manage nature’s contributions to people, as well as help us to better understand the impacts of climate change on biodiversity,” Slingsby said.

The region is one of the world’s 36 biodiversity hotspots with “exceedingly high biodiversity but also with exceedingly high threats from habitat loss and degradation, invasive species, altered fire regimes and climate change”, he said.

New frontier

Nasa initiated the project in 2015 when it put out a funding call to develop scoping proposals for its first biodiversity-focused field campaign.

“Nasa has traditionally mounted field campaigns to address scientific problems lending themselves to a combination of satellite, airborne and in-situ sensing,” said Slingsby.

Previous campaigns have focused on carbon, hydrology, fire and sea ice, among others.

“Proposals were received from all over the world but eventually the BioSCape team’s proposal to focus on the Greater Cape Floristic Region and associated aquatic ecosystems was selected. This is not just pioneering for South Africa, it’s pioneering for the world — and so exciting that South Africa gets to be at the forefront!”

Unprecedented airborne data

Two Nasa planes are being used — a Gulfstream III and a Gulfstream V. Slingsby said these were business jets that had been modified to be able to house and operate the instruments, including downward-facing ports and power and cooling requirements.

According to BioSCape, the campaign will collect UV/visible to short wavelength infrared and thermal imaging spectroscopy and laser altimetry LiDAR data over terrestrial and aquatic targets using four airborne instruments: AVIRIS-NG, PRISM, LVIS (Nasa’s Land, Vegetation and Ice Sensor), and HyTES.

“The anticipated airborne data set is unique in its size and scope and unprecedented in its instrument combination and level of detail. These airborne data will be accompanied by a range of biodiversity-related field observations,” it said.

Slingsby added that the sheer diversity of the Greater Cape Floristic Region alone makes “studying biodiversity here a challenge before you consider dynamics like fire, seasonality or drought, but this is also what makes it a super-exciting place to work.”

He thinks a major factor contributing to the Greater Cape Floristic Regionbeing selected “is the feeling that if we can do remote sensing of biodiversity here — we can probably do it anywhere”.

According to BioSCape, remote sensing data can help with detecting and responding to harmful algal blooms that negatively affect fisheries and freshwater provision as well as monitoring the spread of invasive species that alter fire regimes and worsen droughts.

Cutting-edge research will focus on the Greater Cape Floristic Region, which is home to thousands of plant species unique to the area

Cutting-edge research will focus on the Greater Cape Floristic Region, which is home to thousands of plant species unique to the area

Cutting edge

BioSCape is funded by Nasa and the South African government through the National Research Foundation (NRF) via the South African Environmental Observation Network (SAEON) and the joint NEOFrontiers funding instrument with the South African National Space Agency.

According to Slingsby, Nasa has directly invested about R200 million in this field campaign, “but it builds on the costs of developing the instruments etc, which is far more”.

The NRF has funded teams totalling about R20 million, while Unesco has invested R500 000 in outreach and capacity building activities.

“There has been far more in-kind investment in terms of salaries, equipment etc, especially from SAEON, who have been the local driver in developing this project since 2015,” he said.

Mary-Jane Bopape, the managing director of NRF-SAEON, described BioSCape as a “cutting-edge project”, which is a testament to the world-class biodiversity research that is being conducted in South Africa.

“I have worked as a modelling specialist for a long time, and also relied on satellite products, and we know that these don’t represent our local processes well. This is because of the limited observations in our region that are available to calibrate remote sensing products and inform model developments,” she said.

“This campaign means a very high-resolution dataset will be collected and made to serve as a baseline to inform process studies, as well as environmental variability and change, including the impacts of climate change.”

Deeply collaborative

BioSCape is being led by scientists at the University of Cape Town, the University at Buffalo and the University of California, Merced.

Slingsby added that beyond the general goal of the project, which is “improving our ability to map, monitor and understand biodiversity”, what sets the project apart is its deeply collaborative nature, bringing together scientists from around the world.

“We have over 150 scientists — roughly 50-50 the US and South Africa, with a smattering of other nationalities — representing over 30 institutions, including universities, conservation agencies, NGOs, government departments etc, all working towards fundamental and applied outcomes from the project.”

This kind of engagement is essential when working with biodiversity.

“Biodiversity is so place-specific and there’s so much local nuance that it would be near-impossible for a foreigner with no context to derive meaningful insights. Similarly, these technologies are so new, advanced and expensive that, until now, they’ve been out of reach for local researchers and management agencies.”

Blending the global remote sensing experts with the local biodiversity and environmental management experts, “has been such an exciting space and a privilege to be a part of”, he added.

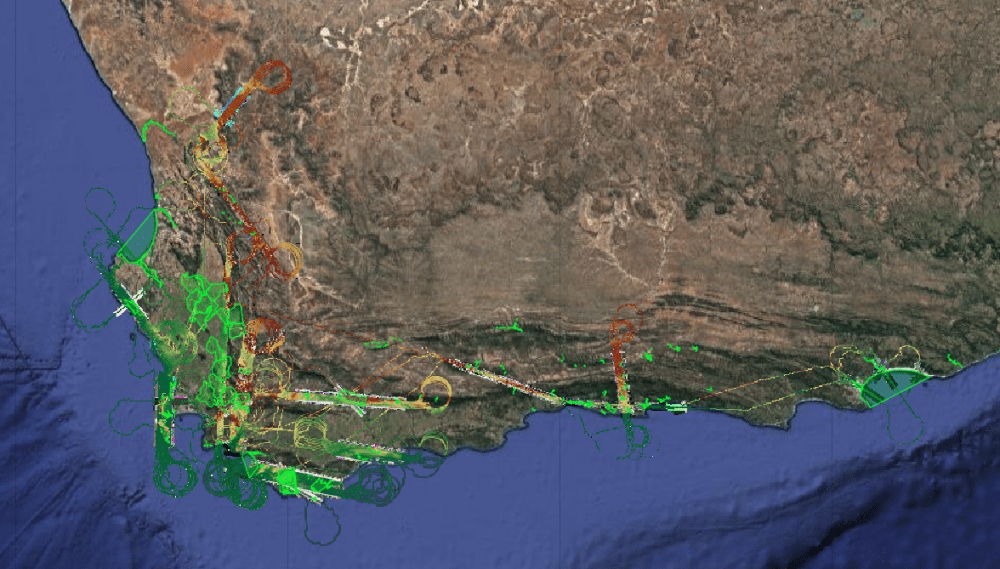

The areas BioSCape have acquired airborne data so far, with the target fieldwork areas indicated in green.

The areas BioSCape have acquired airborne data so far, with the target fieldwork areas indicated in green.

Halting biodiversity loss

“Planet Earth is special,” Erin Hestir, an environmental engineering professor at the University of California Merced, a co-lead of the research project, said in a statement. “It is still the only place we know of in the universe that hosts life. And it is the diversity of that life on Earth that supports our ability to live and thrive here.

“BioSCape is a unique opportunity to advance international scientific collaboration using state-of-the-art technology to tackle one of the greatest challenges facing us today — conserving biodiversity to sustain life on Earth.

“This is the first time Nasa has funded a campaign of this size that is focused on biodiversity,” Hestir said.

“The Cape region of South Africa is one of the most biodiverse places in the world and researchers there are global leaders in biodiversity science. If we can figure out how to do this here, we will enable similar science in many other places around the world and help to support global efforts to halt biodiversity loss and protect nature’s contributions to people.”