The House of Lords is expected to pass legislation that will make it illegal for citizens to bring home any animal body part. (JENS-ULRICH KOCH/DDP/AFP via Getty Images)

The United Kingdom’s Campaign to Ban Trophy Hunting aims to stop hunters travelling to South Africa and other destinations by pushing for a law that will make it illegal for citizens to return home with their trophies.

This coincides with South Africa’s plans to end the captive breeding of lions for hunting (called “canned lion” hunting) and the lion bone trade as proposed in a draft policy published in 2021 on the conservation and ecologically sustainable use of elephant, lion, leopard and rhino.

The Hunting Trophies Bill (Import Prohibition) started its journey through the British parliament in July 2022. It passed unanimously at each stage but ran out of time in the House of Lords. A new cross-party bill is due to receive its second reading in parliament on 22 March.

South Africa is the most popular destination for British trophy hunters who fly to a growing number of countries in search of trophies, according to the campaign’s founder Eduardo Goncalves.

Records from the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) show that in recent years, British hunters have brought home trophies from more than 30 countries, including Argentina, Botswana, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Kenya, Malawi, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Croatia, Lithuania, Pakistan, Canada and the United States.

“Britain effectively ‘invented’ modern-day trophy hunting and brought it to Africa — with catastrophic effects. As many as 20 million animals were killed by mainly British ‘explorers’ and hunters in the 19th century,” Goncalves said.

“The quagga — a zebra-like creature — is thought to have gone extinct as a direct result, with the last animal in the wild shot by a member of the British royal family. Trophy hunting has no history in Africa before the arrival of the British. It is thus appropriate that Britain should lead international efforts to bring an end to this cruel, archaic industry,” he said.

Britons were among the leading trophy hunters in the colonial era and remain so today. Scotsman John Alexander Hunter, who died in the 1960s, shot a world record 1 500 rhinos, 1 400 elephants and 600 lions.

Malcolm King, a British businessman, has won most of Safari Club International’s top awards for shooting large numbers of animals — 650 from more than 125 species. Abigail Day, a London lawyer, has won the Diana Award, Safari Club International’s award for the world’s leading female trophy hunter.

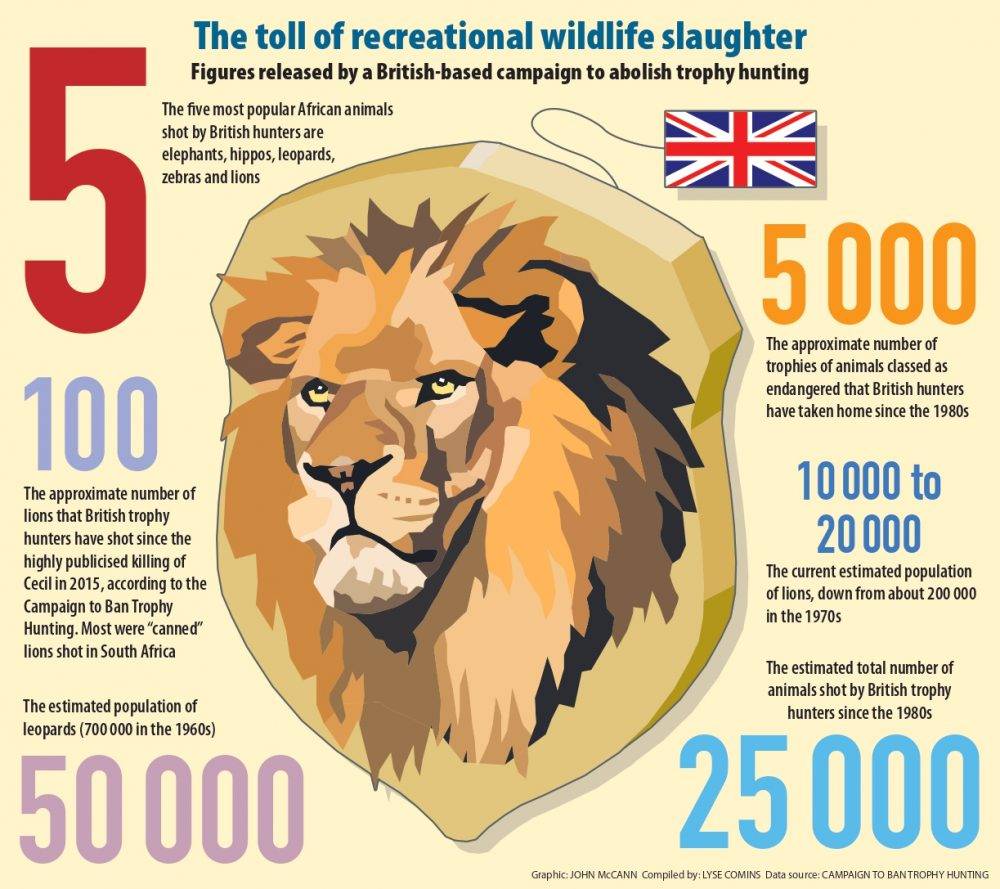

An investigation by the Campaign to Ban Trophy Hunting found British hunters have shot about 100 lion since the highly publicised killing of Cecil the Lion who, in 2015, was lured out of Zimbabwe’s Hwange National Park to be illegally hunted by an American dentist. Most were canned lions shot in South Africa.

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

Described by environmentalists as a sport of “narcissist elitism” and by celebrity campaigners such as actress Joanna Lumley and comedian Ricky Gervais as a “hateful” and “ruthless” pastime, trophy hunting has fuelled the market for canned lion hunting — which included the captive breeding of lions, tigers and cross-bred ligers to be later shot and killed.

“Since the 1980s, British hunters have brought home about 5 000 trophies of animals classed as endangered by CITES. The total number of animals shot by British trophy hunters during this period is estimated to be as high as 25 000,” Goncalves said.

The five most popular African animals shot by British hunters are elephants, hippos, leopards, zebras and lions. The population of the critically endangered African forest elephant and endangered African Savannah elephant on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of threatened species has declined by up to 20% over the past decade.

Leopard numbers are believed to have fallen from 700 000 in the 1960s to about 50 000 and the lion population has crashed from about 200 000 in the 1970s to between 10 000 and 20 000 today. Trophy hunting is cited in research as having contributed to the crisis, Goncalves said.

In terms of the scale of trophy hunting, a study by the International Fund for Animal Welfare found that 1.7 million animals were shot by trophy hunters from 2004 to 2014. This equates to one animal every three minutes.

After the Campaign to Ban Trophy Hunting was launched in 2018 both the Conservative and Labour parties included a pledge in their 2019 election manifesto to ban British hunters from bringing animal trophies into the UK.

A public consultation into the proposed ban — during which 44 000 stakeholders were consulted, including African governments and citizens, wildlife conservationist charities and scientists — found that 85% supported a trophy import ban. A poll last year showed that 86% of British voters supported the ban.

“There is unstoppable momentum for a ban to happen sooner rather than later. There is very strong support for the bill among parliamentarians of all parties, the general public, and some of Britain’s leading and most respected public figures,” Goncalves said.

Lumley said this week: “I have always considered trophy hunting the lowest of the low: contemptible, hollow triumphalism which we would laugh to scorn if the consequences weren’t so utterly grim and cruel. Weasel words and twisted evidence will try to show the benefits of this hateful pastime, but the truth is as plain as can be — killing animals for fun is just disgusting.”

Gervais said British trophy hunters are “among the most ruthless of the lot”.

“They joke about having a few beers and shooting monkeys. They laugh about shooting cats out of trees. They brag about luring leopards with bait so they can shoot them at point-blank range,” he said.

“They celebrate blasting big holes out of zebras and killing some of the world’s biggest lions, elephants, and rhinos. All trophy hunting needs to stop. It’s just as wrong to kill a reindeer for kicks as it is to kill a rhino. We don’t have the right to murder living creatures for entertainment.”

In South Africa, the draft policy published in 2021 envisions restoring natural landscapes with thriving animal populations and aims to end captive breeding of lions and activities that do not promote humane practices, ultimately closing the commercial captive industry.

In addition the government published in October 2023 a draft notice prohibiting certain activities involving African lion, including the establishment or registration of new captive breeding facilities, commercial exhibition facilities, rehabilitation facilities or sanctuaries and the keeping of the animals in any other new controlled environment.

Louise de Waal, the director of the award-winning Blood Lions documentary film and manager of a global campaign to stop the captive lion industry and canned hunting believes the closure should be staged over several years.

“If trade out [where a facility can trade their existing animals under specific conditions to close the business] is not part of the closure of the industry, a substantial number of healthy lions may need to be euthanised, because the capacity of true sanctuaries to rehome healthy lions is very limited. This is the unfortunate outcome of an ugly industry that has been allowed to grow over the last 30 years and created such vast problems,” she said.

Conservation ecologist Nkabeng Maruping-Mzileni agreed. “[For] those [places] that are already in existence, the females will be sterilised to prevent increasing the number of animals and slowly allowing the facility to fade away.”

She believes canned trophy hunting has “little to no conservation value except in cases where it is mimicking natural processes such as removing males that no longer breed, promoting genetic turnover or reducing population density”.

“However, as a business model, if it is to survive then the approach and purpose needs to be re-evaluated,” she added.

“I have often heard the expression ‘if it pays, it stays’ and this has not sat well with me because it promotes a narcissistic elitism when taken in the context of canned trophy hunting,” Maruping-Mzileni said. “Industry morphs and changes. It is possible to have a business model that was once relevant to become redundant in an evolving society.”