Excessive: Mining firm Sibanye-Stillwater shareholders voted against the proposed R55.6 million payment for chief executive Neal Froneman. Photo: Waldo Swiegers/Getty Images

Cyril Ramaphosa, who was re-elected as president last Friday with the help of the ANC’s partners in the new government of national unity, has a lot of work to do when he gets back behind his desk.

There are 29 bills awaiting his signature. Among those is legislation that will reform executive pay structures, addressing the vast pay gaps at South African firms: The Companies Amendment Bill.

South Africa’s largest mining company, Sibanye-Stillwater, has found itself at the centre of public debate over executive pay.

On the eve of the country’s general election, the mining company was in the throes of another kind of vote — one that would determine whether its remuneration report would pass muster.

And, for the third time in a row, it did not. Sibanye failed to obtain the 75% and above required to pass a report after shareholders holding a 25.08% stake in the company voted against the proposed remuneration structure, including a R55.6 million payday for chief executive Neal Froneman.

Last year, 47.92% voted against the report, which detailed Froneman’s R190 million remuneration package. And in 2022, just over 26% voted against the report, which included the chief executive’s astounding R300 million paycheck.

The latter amount was the subject of widespread public scrutiny after Sibanye fought a demand by gold miners for a R1 000 pay hike, which the company said was not sustainable. The impasse lasted three months.

Once the Companies Amendment Bill is signed into law, remuneration committees that fail to receive shareholder sign-off on their reports for two years in a row will have to step down.

As it stands, the shareholder vote against the implementation of the remuneration report is a non-binding, advisory vote, meaning the company is required to hold discussions with the dissenting shareholders — but is not compelled to act.

Kwanele Ngogela, senior inequality analyst at nonprofit shareholder activism organisation JustShare, said executive remuneration should be reasonable in the context of overall employee remuneration in an organisation.

“It is difficult to see any reasonableness in the issue of executive remuneration in the South African context,” Ngogela said.

“It has turned into a feeding frenzy with no consequences for executives who fail to deliver results that justify the exceptionally generous pay they receive while workers at the lower level continue earning a pittance.”

FormerWoolworths chief executive Ian Moir received a hefty golden handshake after his disastrous acquisition of David Jones caused the company’s value to tank by more than 60% in seven years.

An extraordinary 82.24% of shareholders voted against the retailer’s remuneration implementation report at the group’s annual general meeting in 2020. The huge opposition was largely in response to Moir’s R77 million exit package.

Based on the current governance framework, the King Report on Corporate Governance, remuneration committees have total control over the salary of executives, Ngogela noted.

The board of directors or the entire governing body allocates the oversight of remuneration to the remuneration committee, which should mainly be composed of independent non-executive directors.

The committee is expected to get input from external remuneration consultants. While the committee does talk to shareholders, ultimately its members take full responsibility for the amounts paid to executives.

Executive remuneration usually consists of guaranteed pay, short-term incentives and long-term incentives. Both short- and long-term incentives vary and — in theory — correlate with a company’s financial (and sometimes social and environmental) performance.

The guaranteed pay is made up of a fixed salary and other benefits, which vary from company to company, such as retirement or pension benefits, medical aid and death or disability benefits.

“This is not an onerous responsibility, because the committee will invariably point to benchmarking exercises to support their decision and justify the amount they are awarding,” Ngogela said.

“This means that the remuneration committees of all these listed companies move as a pack because they are benchmarking against each other.”

Annamarie van der Merwe, executive chair of the FluidRock Governance Group, said remuneration should be a matter for the board to approve based on the remuneration committee’s recommendation.

“My concern is that the policy often only provides high-level principles with substantial ‘room to manoeuvre’. And it is here that a remuneration committee can get it wrong if they don’t carefully consider the potential consequences of the package and in particular the short- and long-term incentives,” Van der Merwe said.

“There are always potential unintended consequences. There are studies that show the unintended consequences of reward structures being one of the top causes of [corporate] disasters.”

High executive pay is usually justified when a company produces exceptional profits or its share price has performed well, Ngogela said.

But often improved company performance is the result of external factors. For example, increases in mining profits may be because of high commodity prices. Higher interest rates could buoy banking stocks and profits.

Ngogela noted that, for directors who have served on boards for a long time, it can be in their interest to push executive pay higher. Timothy Cumming has been the chairperson of Sibanye’s remuneration committee since 2018 and has been serving on the board since 2013.

“The members of the remuneration committee are part of what we term the elite corporate class, who are generally interested in helping other members of this class, so there is no pushback when discussing executive compensation,” Ngogela said.

“However, this takes a turn when they discuss the pay of ordinary workers.”

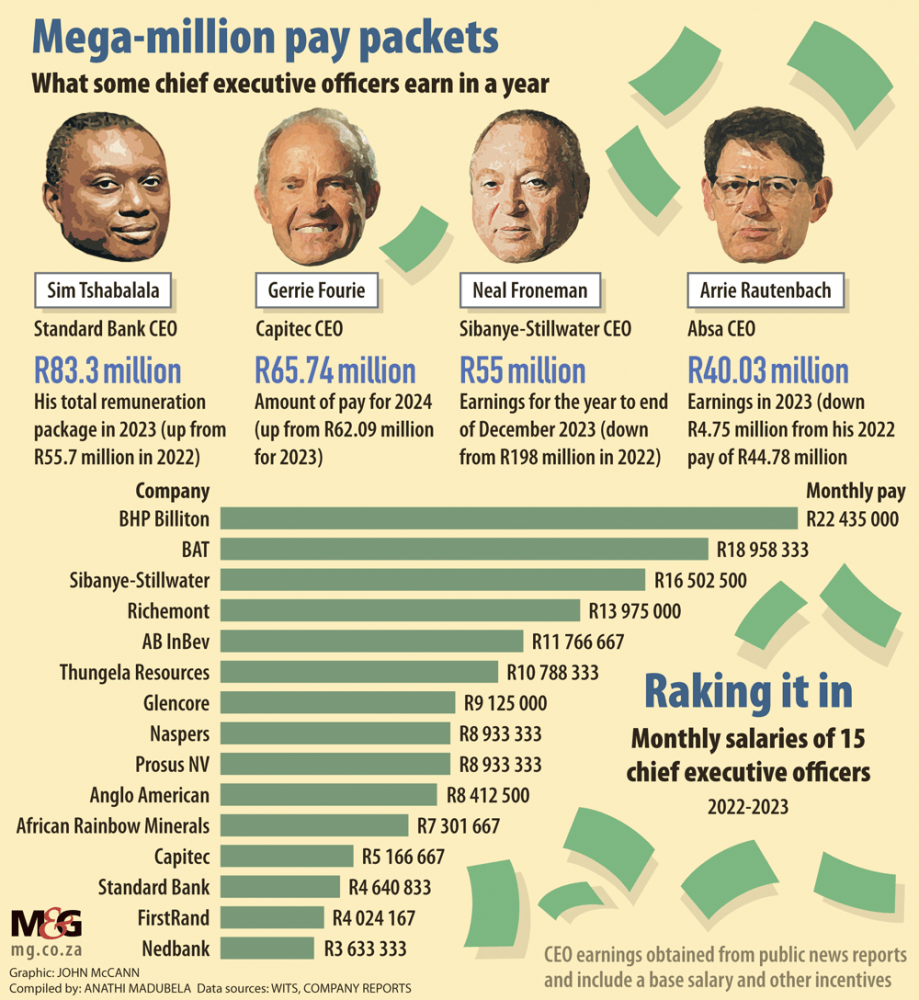

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

In a written submission on the Companies Act, Wits University’s Pre-distribution and Ownership Project found that chief executives earned 150 to 949 times more than the average pay of all South African workers. Researchers used a sample of 15 companies to make this finding.

Sibanye wasn’t the worst offender, with Froneman earning 698 times more than the firm’s average worker in 2022-23. Another mining company, BHP Billiton, topped the list.

The mining industry, which has some of the highest-paid bosses, is vulnerable to wage-related protests.

Sibanye took over from Lonmin after the Marikana massacre, during which 34 mine workers were killed. While mine workers were on strike to be paid R12 500 a month, company reports showed that former Lonmin chief executive Ian Farmer earned R1.2 million a month the year before.

“These big institutions rarely oppose generous remuneration and decisions because of the conflict of interest and what we call corporate cronyism,” Ngogela said.

“We have a prevalent practice of favouritism where people in powerful positions are awarding positions to their friends or trusted colleagues who are also being paid excessively.”

Ngogela said introducing worker-appointed directors to boards could add another layer of oversight to remuneration committees. “They would counter the very strong inclination towards that group to think of the remuneration committee moving as a pack. This may be a necessary level of oversight,” he said.