Operations: Water trucks supply residents (above) while maintenance is carried out in Johannesburg. (Photo by Gallo Images/Sharon Seretlo

After six days without water earlier this month, this week Linda Arnold* once again braced herself for dry taps in her suburb of Malvern, in eastern Johannesburg.

On Monday, bulk water supplier Rand Water embarked on the final phase of its Palmiet pump station maintenance, which reduced pumping at the Alexander Park reservoir, which supplies Arnold’s neighbourhood, to 76% for 40 hours. She had little faith that water supply would be promptly restored.

“Our water was meant to be off for 48 hours for maintenance but we didn’t have it for nearly a week. I had to fill buckets from my swimming pool to flush the toilet,” said Arnold, who suffers from osteoarthritis. “My husband bought a 600-litre JoJo tank [but] we [still] almost ran out of water.”

Since September, municipal utility Johannesburg Waterr has throttled the Alexander Park reservoir in the evenings to build up capacity in the supply zone. Arnold is frustrated by how these ongoing water outages have become the “new normal” in the city’s thirsty eastern suburbs.

She recently returned from hospital after being treated for mental health issues and worries about how the water crisis will affect her daughter, who is due to give birth.

“My anxiety and body can’t cope. Imagine not bathing, not doing washing, not being able to do all of your dishes, just the essentials because you have no water supply services,” she said. “Every night they switch off our water between 7pm and 9pm and it comes back the following morning. But you don’t know if you’re going to actually wake up having water,” she said.

Another Malvern resident, Mike Spadino, said he had to give his 89-year-old mother medicine to stop her from having to use the toilet.

The Malvern clinic had to shut its doors after being open for only three hours a day in recent weeks, Spadino, who is the chair of the Malvern Clinic Committee, added.

“We had to close because we ran out of water. We had arguments with people who can’t understand that you can’t run a clinic without water. And we’re looking at 500 to 600 people a day who come to Malvern clinic.”

The Alexander Park reservoir supplies areas including Kensington, Malvern, Jeppestown, Bruma and Bezuidenhout Valley. On Tuesday, Johannesburg Water said it was “currently empty because of no or poor incoming supply”.

It added that customers in the supply zone “will experience poor pressure to no water. The outlet will close at night to build capacity”.

As they traversed some of the city’s oldest suburbs in the east on their “Tour de Leak” last week, Farah Domingo and Ingrid Bester, both from the Johannesburg Water Crisis Committee, highlighted a major source of the drain on the Alexander Park reservoir: prolific and severe water leaks from burst pipes.

“The closest suburbs to the Alexander Park reservoir — Jeppestown, Malvern, Kensington, Bertrams and Bez Valley — those are the oldest suburbs that the reservoir feeds and they’ve all got water issues,” Domingo said.

The activists pointed to the seemingly abandoned excavated worksite of one leakage in Bertrams, which has resembled a “big crater” for the past year, while another on Cumberland and Queen Streets “flows like a river”, Domingo said. The mangled bumpers of vehicles lay scattered nearby from their violent encounters with the cavernous hole.

“It’s the same all over, leaks and holes and no repair,” muttered Domingo. “When the water is running rampant like this, the reservoirs are emptying faster than they are filling.

“I would say it’s from Rhodes Park all the way down to Park Meadows; that section is so old that the turning off of the reservoirs, switching [them] back on again and the pressure issues have created the problem with the infrastructure, which is leading to all the multiple leaks and damage,” she said.

Bester interjected: “If we are asked to look after water, save water and cut down our use, why is Joburg Water not doing the same? Why aren’t they proactively fixing leaks and responding to calls that have been logged?”

Water leaks are a national problem, according to Ferrial Adam, the executive manager of activist group WaterCAN.

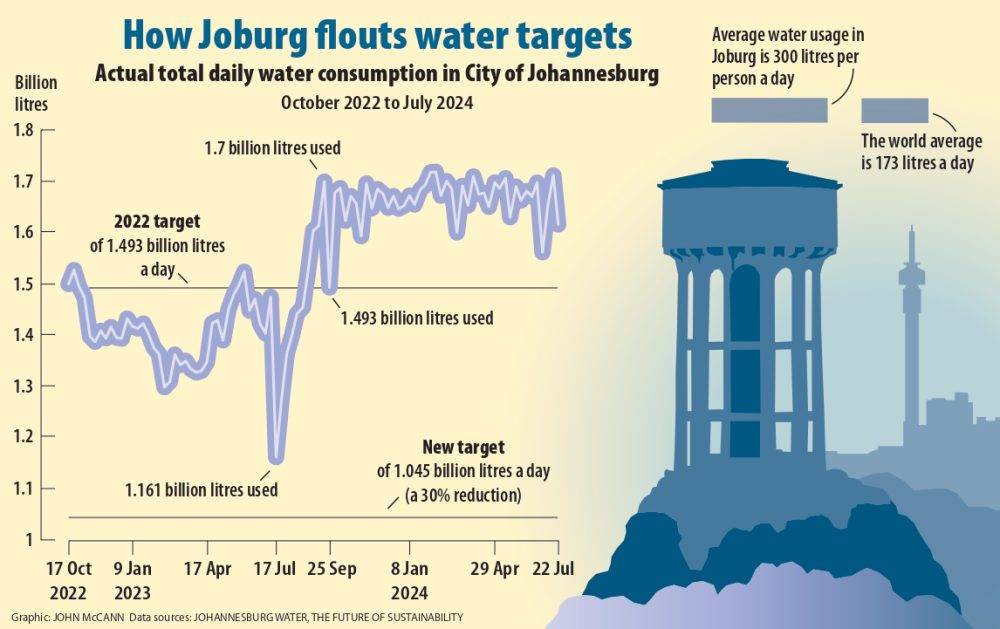

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

“It does put strain on reservoirs because if we take the City of Johannesburg, for example, if they’re losing at least 25% of their water through leaks … that means that your reservoir is emptying too fast and you can’t fill it up,” she said, adding that the non-revenue loss is much higher at about 44%.

What “boggles my mind” is the trenches that are dug to find leaks instead of sending in a camera. “But what’s happening is they build craters; just topping it up with sand, and that puts more pressure on the leaks. Yes, there’s old infrastructure, but it doesn’t feel like there’s a consolidated effort that attacks the leaks so that it’s long-lasting and sustainable instead of just Chappies being used to plug up a bloody hole,” Adam said.

Water interruptions can be caused by a number of things, including leaking and burst pipes and poor bulk supply, said Nombuso Shabalala, the spokesperson for Johannesburg Water.

The standard response time for attending to burst and leaking water pipes is 48 hours and three days for a leaking meter. “However, these response times can fluctuate and be delayed according to the nature and magnitude of the work that need to be done, the machinery needed, as well as the human labour needed,” Shabalala said.

For example, the repair process includes the response team initiating an investigation, isolating the water supply and excavating to expose the damaged pipe.

“Once the water flow is stopped, they proceed with assessing what kind of material is needed, sourcing the material and then finally repairing the pipe. Furthermore, in some cases, a welder or some other specialist may be needed to complete the work and may not be available on that specific team.”

In such cases, she said, that specialist would need to be called in from another depot or team to assist, which further delays the process. “These kinds of issues contribute to the delay of the repairs being completed.”

Shabalala said the turnaround time for backfilling — which refers to placing soil or other materials such as cement and crushed rock back into a foundation or trench — was five days, and that for reinstatements — closing a site beneath a pavement or road after it has been excavated to replace or repair water pipes — was 10 days.

“However, these turnaround times are affected by various issues, including the magnitude of the work to be performed. Some backfilling and reinstatement jobs are done internally by Johannesburg Water teams and the medium- to large-scale jobs are outsourced using service providers,” she said, adding that other reasons for delays include backlogs of reinstatement work, resource availability as well as weather conditions.

Pressure has mounted for Kabelo Gwamanda to be removed as Johannesurg’s mayor because of, among other reasons, intermittent water supplies since 2023 and prolonged water cuts in recent weeks.

Adam agreed that he needs to go. “It’s not party-specific; we just want a mayor who’s going to get the work done. For the most part, [Gwamanda] hasn’t given people a sense of confidence about being on top of the water issue in Johannesburg, which has been the most pressing issue in the past 12 months across the city. He needed to give people confidence but he didn’t.”

*Not her real name.