Storm: The smiles mask the tension between President Cyril Ramaphosa and his Rwandan counterpart, Paul Kagame, over the escalating conflict fuelled by Rwandan troops in eastern DRC. The two leaders met in Kigali in April last year. Photo: GCIS

An unprecedented public row between President Cyril Ramaphosa and Rwandan President Paul Kagame has underscored the complexity of the conflict in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and of efforts to contain it.

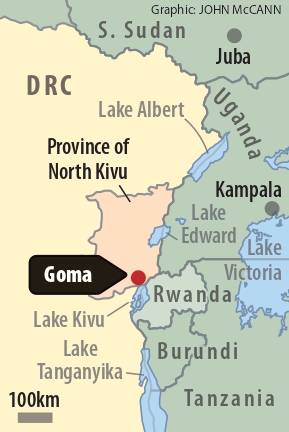

Ramaphosa has twice spoken to Kagame in the past week in which Rwandan-backed M23 rebels captured Goma, the capital of North Kivu province and a vital node for humanitarian operations in eastern DRC, raising fears of renewed war in the Great Lakes region.

South African diplomats and the presidency have said that in those conversations Ramaphosa pressed the need for an immediate ceasefire and a resumption of regional peace talks. They also suggested that Kagame said he was in agreement.

Kagame took to X late on Wednesday to deny that version in combative terms. “What has been said about these conversations in the media by South African officials and President Ramaphosa himself contains a lot of distortion, deliberate attacks, and even lies. If words can change so much from a conversation to a public statement, it says a lot about how these very important issues are being managed.”

He responded directly to a message Ramaphosa had posted, in which the latter defended the role of the SAMIDRC, the Southern African Development Community (SADC) peacekeeping mission in eastern DRC which includes a sizeable South African contingent. Ramaphosa’s initial statement included the line: “The fighting is the result of an escalation by the rebel group M23 and Rwanda Defence Force (RDF) militia engaging the Armed Forces of the DRC (FARDC) and attacking peacekeepers from the SADC Mission in the DRC (SAMIDRC).” The reference to RDF militia has since been deleted.

“SAMIDRC is not a peacekeeping force, and it has no place in this situation,” Kagame said. “It was authorised by SADC as a belligerent force engaging in offensive combat operations to help the DRC government fight against its own people, working alongside genocidal armed groups like FDLR [Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda] which target Rwanda, while also threatening to take the war to Rwanda itself.”

Kagame added that the SAMIDRC has displaced “a true peacekeeping force”, in the form of the East African Community Regional Force, and that this had contributed to the breakdown of peace talks.

South Africa lost 13 soldiers in the past week as the M23, the latest in a long line of Tutsi-led rebel movements in eastern DRC advanced on Goma.

Ramaphosa’s rush to secure a ceasefire is motivated by the need to prevent further casualties and to provide relief for troops trapped in their bases in Goma and Sake, some 30km north-west of Goma, by the rebels.

There have been suggestions of sending air support from local diplomats, who stressed that the Congolese military folded under the rebel offensive, and that South African soldiers, along with troops from Malawi and Tanzania who make up the rest of the SAMIDRC mission, found themselves left as the ill-equipped last line of defence.

But analysts say logistically this is nigh impossible, and cannot be done swiftly. It is also not South Africa’s decision alone but one SADC would need to approve.

And it will contradict Ramaphosa’s refusal, in telephone conversations with the DRC president, Felix Tshisekedi, to agree to send military reinforcements to the region.

Kagame has come under international pressure to withdraw from the DRC, with traditional supporters Britain and France changing their tone towards Kigali. British foreign secretary David Lammy said he told Kagame that $1 billion in global aid is “under threat when you attack your neighbours”.

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

The warning recalled the withholding of aid by a number of Western donors, including the European Union, in 2012 when the M23 captured Goma. It withdrew less than a fortnight later as pressure mounted on Kigali, which relies on foreign aid for about a third of its national budget.

The renewed pressure appears to have had no immediate effect. News agencies have reported that the rebels were advancing towards Bukavu, the capital of South Kivu. Reuters quoted a local resident as saying they had tried to take Nyabibwe, 50km north of Bukavu.

Kagame has been defiant about his backing for the M23 while dismissing recent United Nations reports that he sent 4 000 soldiers across the border to support their offensive. He insists Rwanda’s actions are defensive.

South African officials have publicly ignored his denials and warned Kagame to stop fuelling the conflict, echoing a call by UN secretary general António Guterres on “the Rwanda Defence Forces to cease support to the M23 and withdraw from DRC territory”.

International Relations Minister Ronald Lamola on Tuesday told an emergency meeting of the African Union Peace and Security Council: “We would also like to condemn Rwanda for its support of the M23 as clearly proven by various United Nations reports of experts. We therefore call upon Rwanda to cease its support to the M23 and for its forces to withdraw from the DRC.”

Privately, South African diplomats have said they expected Kagame would use this month’s territorial gains as a bargaining chip if peace negotiations were to resume. They said he would try to extract concessions to secure Rwanda against Hutu extremists in eastern DRC, a theatre of cyclical ethnic conflict since the 1994 Rwandan genocide. This remains his justification for any role in eastern DRC, but he has also been accused of benefitting from the pilfering of the regions’ mineral riches.

In a separate post on X on Wednesday, Kagame said he had agreed with US Secretary of State Marco Rubio on “the need to ensure a ceasefire in Eastern DRC and address the root causes of the conflict once and for all”.

His message to Ramaphosa cast him as holding the upper hand, and his counterpart as begging for help for the neutralised South African contingent. “President Ramaphosa has never given a ‘warning’ of any kind, unless it was delivered in his local language which I do not understand,” he wrote. “He did ask for support to ensure the South African force has adequate electricity, food and water, which we shall help communicate.”

He denied that South African troops were killed by the M23, saying Ramaphosa conceded that the Congolese army (FARDC) was responsible for the fatalities.

The South African National Defence Force has said four of the soldiers were wounded when the M23 and the FARDC traded mortar bombs in Goma, while the rest died in fighting near Sake.

Kagame concluded his message to Ramaphosa with a clear warning of his own.

“If South Africa wants to contribute to peaceful solutions, that is well and good, but South Africa is in no position to take on the role of a peacemaker or mediator. And if South Africa prefers confrontation, Rwanda will deal with the matter in that context any day.”

Jakkie Cilliers, head of the Institute for Security Studies’ African Futures and Innovation programme, said the spat between the two presidents was “a storm in a teacup”.

“I think all need to take a deep breath and de-escalate,” he said.

“No one is going to go to war.”

Lamola’s office has said Pretoria will continue to communicate with Kigali and denied that Ramaphosa’s message had been a distortion of the discussions thus far.

“The diplomatic channels remain open, with our unwavering emphasis on a ceasefire. Our commitment remains steadfast in finding a long-lasting and peaceful solution to the conflict,” said Lamola’s spokesperson, Chrispin Phiri.

Ramaphosa has long had a fraught relationship with Kagame, but his other challenge is bringing Tshisekedi to accept that there will be no regional military rescue for the DRC and that he must finally agree to negotiate directly with the M23.

The DRC president snubbed a virtual crisis summit of East African nations on Wednesday organised by Kenya’s President William Ruto. Kagame attended, as did the presidents of Burundi and Tanzania.

Instead, Tshisekedi delivered a television address in which he accused the international community of “inaction” and vowed military victory, saying: “We will fight and we will triumph.”

South African officials have, off the record, described his stance as delusional given the state of his army, and the reluctance of the nations to whom he has turned for help to be drawn into a regional war.

Ramaphosa has in recent months impressed on both the Congolese and Rwandan counterparts that South Africa could ill-afford its deployment as part of the SAMIDRC and wanted to see a resumption of negotiations, after the Rubavu ceasefire accord reached in mid-2024 collapsed, that would allow the mission to wind down.

His office was emphatic this week though that in the current situation, a summary withdrawal was out of the question, despite domestic pressure over the number of fatalities South Africa has suffered.