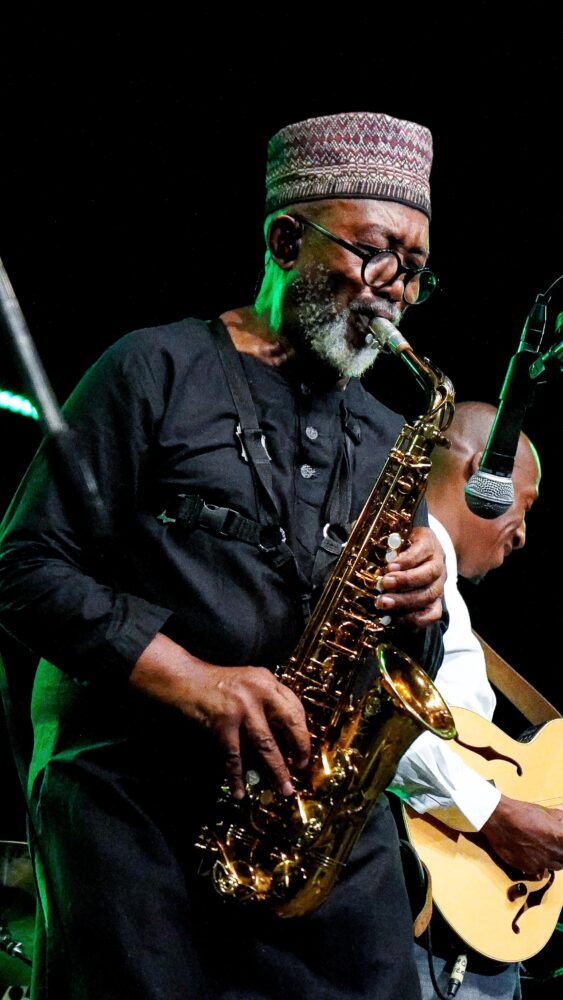

Township child: Sipho ‘Hotstix’ Mabuse will perform at BMW Art Generation Vol III on 30 August at the Nirox Sculpture Park in Johannesburg. Photo: Arthur Dlamini

If you’ve not heard of Sipho “Hotstix” Mabuse, I’d be curious which rock you’ve been living under. I’ve not only heard of him, but consider myself a certifiable stan.

Imagine my intense glee as I manoeuvred my rickety car over countless potholes, hoping against all hope that it would make it all the way to his house in Pimville, Soweto.

When I arrived, unsure because of the informal numbering system, a big yellow house with a motif of huge piano keys on the facade told me this must be the place. I gathered myself to meet a man whose music has defined a nation.

I love your library! Did you grow up with books and music?

Well, not really much with books. Books I developed a love for as time went on. But music is something that has always been there. I mean, there are weddings, there are funerals — everywhere you go there will always be music.

Music is something that all of us, as Africans, grow up with. I was privileged because I had uncles who loved to sing, from my mother’s side, bacul’ ingoma — like glorious music. Once they’d had their drink, they would just burst into song.

I had three uncles, my mother’s brothers, and she also had two cousins from my grandmother’s youngest brother. They would always gather at my grandmother’s house in the Free State in the border town eMemel, about 50km outside Newcastle. And they would start the music. Wow! You know when people sing freely, not because they are motivated by anything other than pure feeling.

That is where it all started. And, of course, when I went to high school, there was always music at assembly.

It’s something that has just always been part of my life.

But I loved reading, not as I do now. It was really because I was at school, and I would always be asked to be the class reader.

I read that you started playing drums at eight.

Well, that’s a bit exaggerated. I did play drums even before that. But this was more like an introduction. I was born in an informal settlement that had what you’d consider intra-tribal music happening all around and also traditional healing.

My curiosity would invariably drive me to the drumming.

One of the traditional healers who lived opposite my home, Ntate Manwe, would say to me that he could see I liked these things.

I had a sense of rhythm, enough to play what they were all playing at that age. But the actual drums, I only started when I was at high school, when I started the band.

You’re referring to The Beaters — later known as Harari?

Yes.

How did that come about?

The Beaters were something that happened by default because we were all high school students. Maybe it was fate that brought us together, because I don’t believe our objective in going to high school was to start a band.

Legendary musician Sipho ‘Hotstix’ Mabuse reflects on music, art, legacy and preparing to share the stage with younger artists

We went to school because we wanted to be academically endowed.

And probably some of us would have wanted to be doctors, others, teachers, and so on. So, the music thing really happened by default because our headmaster, who was also a musician and choral composer, loved musicians.

There were quite a high number of singers who came from Orlando West High School. But the request to raise funds for certain students who were going to university was a watershed moment for us. That’s how we decided to form The Beaters.

And now here you are and Burn Out is part of every South African’s DNA.

So it seems. I mean, the song was recorded over 40 years ago.

As you were recording it, did you have a sense of what it would become?

Well, I did. It was just incessant … I wanted to listen to it over and over again. Strangely enough, it didn’t take me as long to compose, compared to other songs.

I wasn’t a pianist, but I could just play around on the keys. So I went to the piano and started playing. There was a pianist accompanying me, sitting across from me. I noticed how he responded to what I was doing.

So, I asked the sound engineer to stop everything else and please record what I was playing right then.

“Put this down,” I said. “Before I forget it.” Because I knew by tomorrow, I might have forgotten it completely. So we recorded it.

When I brought in the record company executives — that was Peter Gallo and Ivor Haarburger — and said, “I want you guys to listen to this,” the first thing they actually asked was, “What is this?!” They had never heard anything like it before.

Can I ask who it was about?

[Laughs with a big familiar Ha!, from the belly] Everyone who’s ever been in love and been disappointed.

Do you get tired of being asked about it?

Obviously, it’s a song that’s very close to people’s hearts. When people ask questions about the song, it only means that they love it, you know?

Once people respond or react to something that you’ve done, it’s an honour. So I’m not bothered by how often people ask.

What do you make of this renewed cult following for South Africa’s old-school bubblegum pop?

There’s music we recorded many years ago with The Beaters and Harari and suddenly you hear young artists today saying, “Hey, can I please re-record that music?”

And it’s so special. You think, ‘Wow, I didn’t even realise back then, when we were creating it, that the impact would be felt by younger generations who would want to carry it forward.’

And now those songs are international phenomena. That’s how I think young people should see themselves — as part of something bigger, something global.

We have our own legacy, our own sound, our own history to honour. It’s about that exchange — young people looking to us and us looking to them.

You’ve worked with amazing musicians such as Miriam Makeba, Hugh Masekela, Ray Phiri …

Yeah. I’ve worked with so many good musicians. I’ve really been privileged. I don’t know why, but I’ve managed to amass all that great energy from those sources, except one, Abdullah Ibrahim. He always says too, “Yeah, I know. I’ve seen you work with everybody but me.”

At the BMW Art Generation Vol III event, you’ll be sharing the stage with younger musicians, like Msaki.

I’ve worked with Msaki before. She is so talented. Artists like Msaki, Thandiswa Mazwai, Zoe Modiga and other younger musicians make the kind of work that outlives even the artists themselves.

At BMW Art Generation Vol III, there’s a strong transdisciplinary vibe. How important is it for young people to engage with music and visual art together?

The point you just made is very critical. I once read a book that said that the arts, music, science, technology and everything else together create a holistic person.

So, what we are doing now, with the BMW thing, is all about creativity. A car itself is about creativity. Creating a car. A lot of people may think, now, “It’s just a car.” But what did it take for someone to create and build a BMW? It took an idea. That’s what we are trying to show society.

I see you also collect art. What are your inspirations behind collecting?

Oh yes! This is nothing. I’m an artist, so I appreciate others. Look around, Syria, Sudan, Kenya, Ghana — everywhere I go, I collect. That piece you see there, I bought that in San Francisco almost 46 years ago.

“Hotstix” — where did that come from?

I used to be a hot drummer. [Smiles cheekily.] So, one of my colleagues after I played a solo, said, “Oh Hotstix!” That’s how it came.

What do you love most right now?

Peace.

If there’s anything I love more than art, it’s music, and locally, nothing can ever touch Burn Out.

In Sipho “Hotstix” Mabuse’s warm book- and art-filled home, surrounded by awards, it’s impossible not to feel the hot anticipation of seeing him perform at the BMW Art Generation Vol III on 30 August at Nirox Sculpture Park.

Bringing together musicians, visual artists and cultural thinkers for performances, talks, workshops and installations, this will be one for the real ones. For the culture.