Research from the University of the Witwatersrand shows that more than half of the deaths in newborns and about a third in infants were caused by just two types of bacteria. (Aditya Romansa/Unsplash)

Over the past 10 years, researchers from the University of the Witwatersrand’s vaccines and infectious diseases analytics unit analysed small tissue samples of 1 586 children under five who died at public health facilities in Soweto, southwest of Johannesburg.

With the people in the area living in from informal settlements to structured houses, the cases seen here are a good window into what is likely to be seen in other urban townships in South Africa too, says the team.

The study found that many babies die because of preventable infections.

This is not new knowledge, but it’s the detail in the study’s data that’s so valuable, says Ziyaad Dangor, who heads up the South African leg of the nine-country Child Health and Mortality Prevention Surveillance (Champs) study.

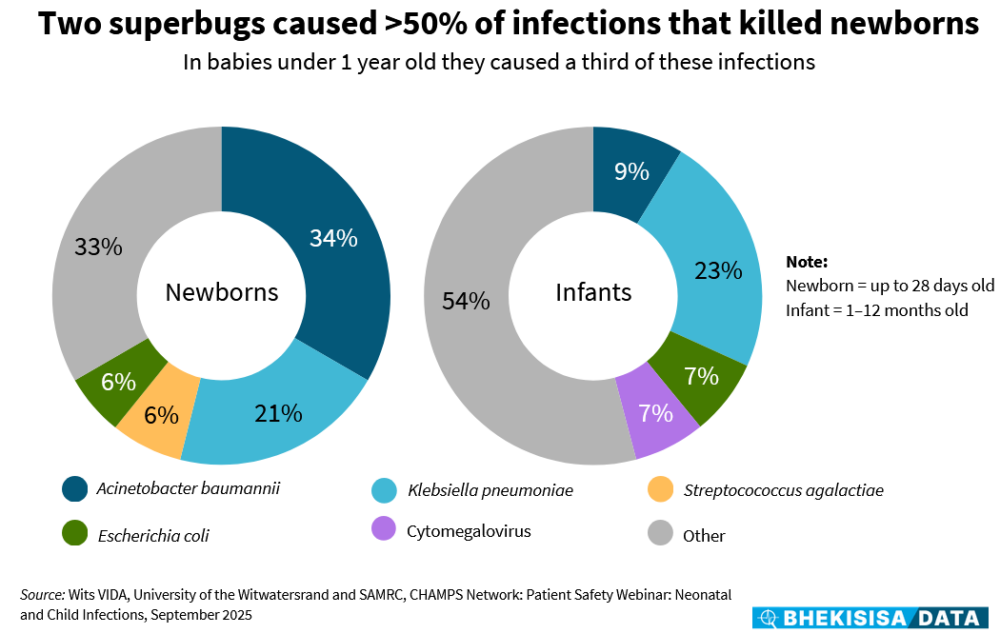

Results show that of the infections that led to deaths, more than half of those in newborns (babies up to one month of age) and about a third in infants (babies between one and 12 months) were caused by just two types of bacteria — Acinetobacter baumannii and Klebsiella pneumoniae — both of which are fast becoming resistant to antibiotics, says Dangor.

Antibiotics can kill bacteria, but when they figure out how to sidestep the medicine — meaning when they become resistant to the drugs by changing themselves because people don’t finish their drug courses or too many people use the antibiotics — this no longer happens.

Child health — including preventing children from dying — was a big talking point at the 80th United Nations (UN) General Assembly in September.

And rightly so.

With only five years to go to the cut-off for meeting the UN’s sustainable development goals, a global report published in March shows that babies dying within the first month of life made up almost half of the roughly 4.8 million deaths in children under five in 2023.

Although the number of children dying before their fifth birthday has halved in just over 20 years — dropping from 77 to 37 per 1 000 live births between 2000 and 2023 — progress has slowed down so much in the last decade that 65 countries won’t make the UN’s target of getting this rate down to below 25 in 1 000 by 2030.

South Africa is one of them.

In 2023 — the last year for which data is included in the report — the country’s under-five mortality rate sat at just under 35 per 1 000 births — almost 1.5 times higher than the ideal. This works out to close to 112 young kids having died in South Africa every day that year, based on UN data. (The rate differs from what StatsSA says it was at that time — around 30 per 1 000 births. However, the statistics agency also notes that the estimates they show “are based on the selected model life table and may differ from similar indices published elsewhere”.)

Many of the under-five deaths are in babies who die either before they’re a month old (called a newborn death) or before they’re one year old (called an infant death).

Although at the current rate of 13.4 newborn deaths per 1 000 births, South Africa is close to the UN’s target of no more than 12 per 1 000, it’s the highest this number has been in almost 10 years.

The number of babies in a population who die young is like a mirror of how healthy a country is, because many of the things that lead to these children’s deaths — like infections, not being able to get medicine or healthcare, or not having clean water, good housing or nutritious food — also affect the health of the rest of a country’s people.

By this measure, things could go awry if the government doesn’t think wisely about how best to spend its health budget, which will likely become even tighter than before as money has to be shifted elsewhere to plug holes left by international funding cuts.

This is why understanding the causes of child deaths is all the more important, says Dangor. “If you don’t know what you’re fighting against, it’s very difficult to treat.”

Here are four takeaways — in graphs — from the South African data so far.

1. On-time screening = fewer stillbirths

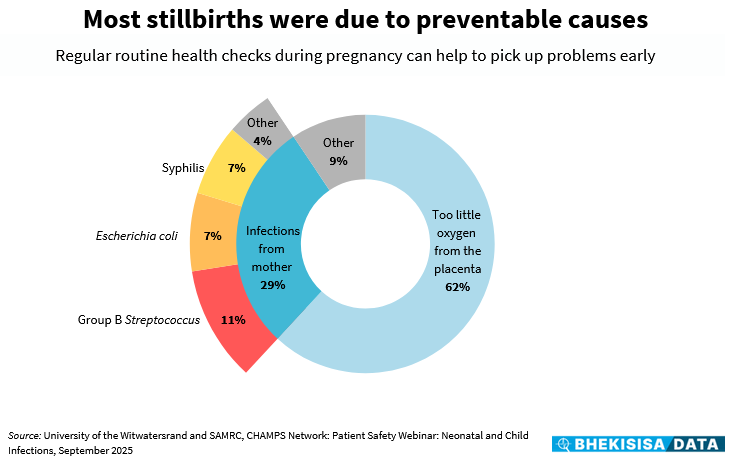

Of the 460 stillbirths investigated in the Champs study, nine out of 10 were because of mostly preventable issues during pregnancy, such as the growing baby not getting enough oxygen while in the womb or an infection passed on from the mother to the foetus.

During pregnancy check-ups, health workers test the expecting mother for conditions such as high blood pressure, which can reduce oxygen supply to the growing baby, or common bacterial infections, such as from Group B Streptococcus (often lying dormant in the genital tract).

Group B Streptococcus is a common type of bacteria, and although it’s usually harmless in healthy adults, it can cause a serious illness known as group B strep disease in newborn babies, with symptoms such as fever, low body temperature and seizures.

Nurses also check pregnant women for the germ that causes syphilis (a sexually transmitted disease). If you’re pregnant and have syphilis, you can pass it on to your baby before birth. Having syphilis during pregnancy can also increase someone’s chances of miscarriage, giving birth too early or stillbirth.

If found early, these issues can easily be treated with medication and good health checks.

But the finding that so many stillbirths were due to preventable factors like these suggest that there are holes in the safety net of antenatal care, says Dangor. It could be because the mother didn’t book for a pregnancy check-up, had a screening test only late during her pregnancy, or she may have tested negative for something like syphilis once and then wasn’t tested again later during her pregnancy, as she should have been.

South Africa’s national guidelines follow the World Health Organisation’s recommendation of eight pregnancy check-ups, and can start within 14 weeks of conception. Despite data from the 2023/24 District Health Barometer showing that close to 70% of pregnant women go to a clinic for at least one antenatal check-up, and usually before 20 weeks, many don’t go back for follow-ups because it’s difficult or costly to get to the health facility or they have to wait in a long queue.

2. Preventing early births = preventing untimely deaths

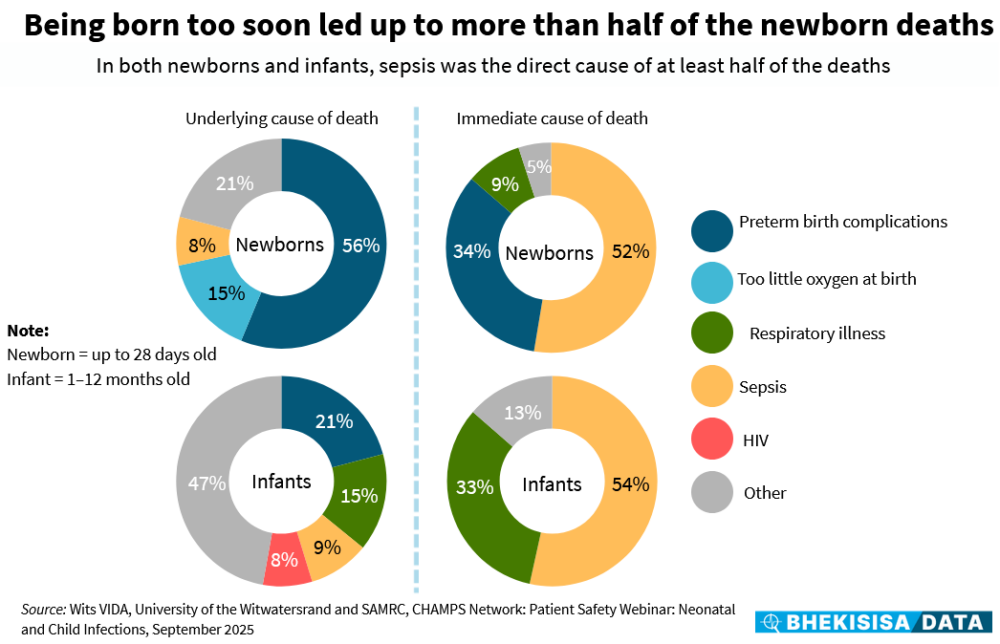

In newborns, issues linked to a baby being born too early were the underlying cause of more than half of them dying, and the immediate cause of death in about a third of this group.

When someone dies, the condition that killed them (called the immediate cause of death) may have been brought on by another existing health problem (called the underlying cause of death).

In the case of children dying within the first year of life, prematurity is a big contributor. A full-term pregnancy is 40 weeks. A baby that is born before 37 weeks — in other words, prematurely — is “not quite ready to be in the world because their organs aren’t fully grown yet”, explains Dangor.

For example, a premature baby’s lungs aren’t strong yet, so they have to be admitted to hospital to be given oxygen. Not only are their bodies weaker than they should be, he says, but being admitted to hospital also means that they have a bigger chance of getting exposed to germs that they can’t fight or that are difficult to treat, as are common in health facilities, and which can then easily lead to sepsis.

Sepsis is when the body’s immune system has an extreme response to an infection that causes damage to tissues and organs. If sepsis is not treated early, it can lead to shock and someone’s organs shutting down.

3. Superbugs = bad for babies

More than half of the infections that led to deaths in newborns and about a third in infants were caused by just two types of bacteria — Acinetobacter baumannii and Klebsiella pneumoniae — both of which are fast becoming resistant to antibiotics.

“Before the Champs study, we knew that, for example, Klebsiella pneumoniae caused infections, but not to the extent that we saw. So, either it’s become much more common in causing a problem or it’s been underrecognised before.”

The same goes for A. baumannii, a stubborn germ common in hospitals which can, for instance, cause pneumonia, and for which there currently is only one type of antibiotic available — with difficulty — in the public sector, and one that doesn’t work all that well in the first place.

Says Dangor: “As a clinician on the ground, it makes you feel helpless.”

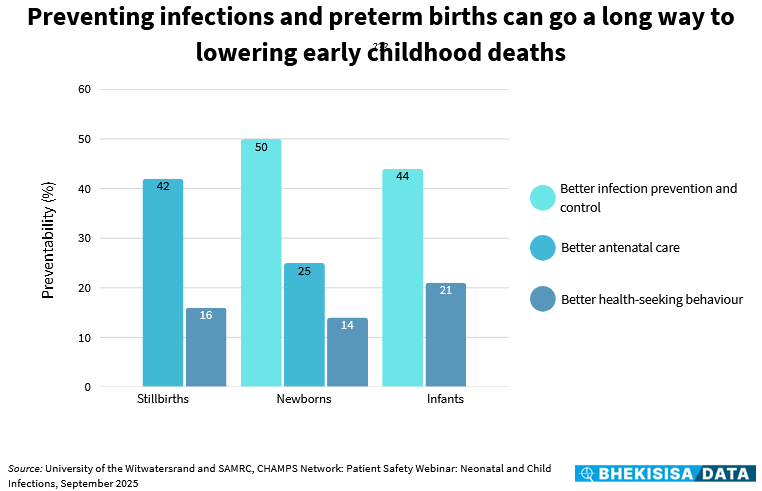

4. Prevention = better than cure

Yet that’s the beauty of having detailed data.

Knowing where the problems are means solutions can be built around it. With few treatment options available for in-hospital infections, it’s “best to limit exposure” by fixing things in the health system before a woman has to give birth, explains Dangor.

There are many ways to do this, says Dangor, with some things being more powerful than others. The data shows that three things — better health checks during pregnancy, preventing in-hospital infections, and helping new moms to know when to ask for medical advice — can go a long way to preventing early child deaths.

The findings don’t put a number on how many deaths would be prevented, though, but rather show where efforts could be best spent to keep children safe, depending on their age group. And this, says Dangor, is a win, especially at a time when international funding cuts to the HIV programme, in particular in South Africa, are putting pressure everywhere in the health system.

Says Dangor: “Anything that’s going to cause reprioritisation of the available budget is going to put pressure on the health system throughout.” And that can have a ripple effect on child health in South Africa — and the country’s development future.

This story was produced by the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism. Sign up for the newsletter.