There needs to be a balance between protecting privacy and saving lives as South Africa debates publicising its sex offender registry

COMMENT

In his 2020 International Women’s Day address, President Cyril Ramaphosa said that, through South Africa’s chairship of the African Union, he will be advocating for the adoption of an African Union Convention on Violence Against Women. To this end, the South African department of women, youth and persons with disabilities has put together a team to serve as advisory committee members in the drafting of this convention, which, it is hoped, will be negotiated and agreed on by all AU member States.

In light of the violence against women in Africa, which has been exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic, it is unsurprising that such a treaty be proposed. Globally, violence against women is a pandemic, and Africa is not spared. This is clear from the protests in different parts of the continent calling for governments to do more to protect women from violence.

The sheer outrage of women protesters who recently took to the streets in Liberia, Malawi, Namibia, Nigeria, South Africa and other African countries was palpable. Their demands were varied, ranging from calling on states to impose harsher sentences for sexual crimes to pleading with the police to be more thorough in their investigations of cases of sexual assault. The common denominator seems to be that states are failing to protect women, whether through inadequate police investigations or lack of structural support for women victims of violence or because of legal loopholes in the legal systems resulting in impunity for perpetrators. In a context in which Africa’s existing domestic authorities are constantly failing to ensure the safety of women on the continent, will a regional instrument adopted by African countries and focused on violence against women bring about positive change?

Existing human rights instruments

By becoming parties to international human right treaties such as the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (Cedaw) and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), African states have made commitments and undertaken international law obligations to protect women from gender-based discrimination, including in its most pernicious form, namely gender-based violence. These international treaties have led many countries to adopt domestic legislation to implement their legal obligations under these instruments.

Cedaw is one of the most widely ratified international legal instruments with only two African countries having not yet ratified it. Nevertheless, of the African states which have ratified Cedaw, more than 10 entered reservations, some of which have the effect of undermining obligations in the convention, including several instances where the purported reservation is incompatible with the object and purpose of the treaty, and therefore unlawful.

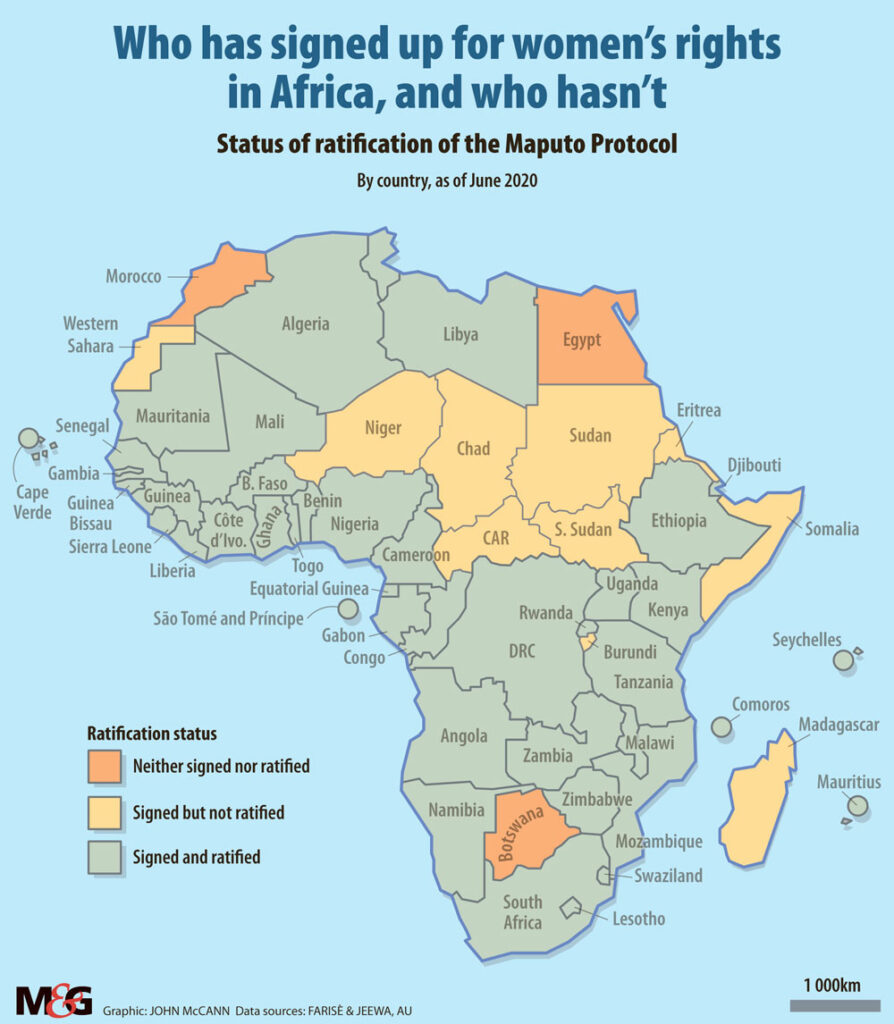

At the regional level, 42 out of 55 African states are also bound by the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa (the Maputo Protocol) and six countries have ratified it with reservations. This is less than those who have ratified the Cedaw. While the Maputo Protocol, like Cedaw, is not exclusively focused on violence against women, it clearly prohibits violence against women by enshrining state parties’ obligations to respect, protect and fulfill women’s rights to life, dignity, integrity and security of the person, among other rights.

Comparable regional instruments

As with most AU treaties, the proposal to elaborate a new treaty focused on violence against women may find inspiration in existing comparable instruments in other regions. For example, in the Americas, under the auspices of the Organisation of American States, member states adopted a regional instrument against gender-based violence against women in 1994, the Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment and Eradication of Violence Against Women (“Belém do Pará Convention”). This was the first convention, adopted in a regional context, which was aimed at eliminating all violence against women. This convention has been relied on in cases before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights; under the convention “all States have a legal obligation to protect women from domestic violence”.

This is a practical application of the principle of due diligence under which states have a legal obligation to take all necessary measures to prevent, investigate, prosecute, sanction and provide an effective remedy for any form of gender-based violence against women. Under international human rights law, including the Belém do Pará Convention, states are liable for acts committed by private parties if they fail to act with due diligence to prevent the violation of women’s human rights. The principle of due diligence has been found by the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women to be universal and a rule of customary international law.

The Belém do Pará Convention has been successful in putting pressure on states in the Americas to promulgate legislation giving effect to the rights of women. Following the case of Maria da Penha v Brazil, despite Brazil initially failing to implement the inter-American commission’s recommendation, it later promulgated Law 11.340/06. This law is commonly known in Brazil as the Maria da Penha law, establishing a system of courts that would focus exclusively on violence against women. In Europe, the Council of Europe has adopted a Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence (the Istanbul Convention). Although the Belém do Pará Convention has been in effect for 25 years, it is still too early to assess the effect of the Istanbul Convention, which was in place from 2014.

These two regional conventions may have been useful in their respective regions, but it is still unclear whether the solution to the plight of gender-based violence against women in Africa is a similar instrument with a sole focus on eradicating this scourge from the continent.

Do we need another treaty?

There is no simple answer to the question of whether an African treaty on violence against women will improve the protection of women from gender based violence in the continent. The lack of a simple yes or no answer is based on various factors. First, experience has shown that African states are either slow in ratifying regional treaties geared at the protection of the rights of women, or do so with a myriad of reservations. This could mean that certain states may do the same with an African violence against women treaty.

Second, even if several states freely accept to be bound by such a treaty, victims of violence would have serious challenges in enforcing their human rights at the regional level. Only 30 states have ratified the protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Establishment of the African Court; out of these only six have deposited declarations recognising the competence of the African Court to receive cases directly from nongovernmental organisations and individuals. Côte d’Ivoire and Benin withdrew their declarations early this year, and Tanzania and Rwanda withdrew theirs in 2019 and 2017 respectively.

This seriously inhibits access to judicial remedies at the regional level for human rights violations, including violence against women. The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights has adopted landmark decisions, such as those delivered in the case of EIPR and Interights v Egypt, where the commission outlined the state’s obligation to protect women from violence. The commission has also produced useful resolutions and guidelines on protecting women from violence, but its recommendations are not binding on states, which, in turn, limits the commission’s ability to deliver effective remedies.

Third, where states have ratified these treaties and introduced domestic laws targeting violence against women, there have been problems in implementation and accountability at the domestic level. For instance, although article 26 of the Maputo Protocol requires member states to report every two years to the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the different measures undertaken to achieve the complete realisation of the rights found in the protocol, only 15 state parties have followed through with the reports, signalling poor compliance with their reporting obligation.

What now?

Different mechanisms to address violence against women are all pieces of a bigger puzzle that aims at completely eradicating this plague. A regional African instrument that focuses solely on tackling violence against women is not a silver bullet that will solve problem on its own. It does, however, have the potential to contribute to an enabling environment for positive change by symbolising the seriousness of African states’ commitment to tackling violence against women in Africa. If this treaty is developed and adopted by the AU, it would be a step in the right direction in displaying the political will of African states to eliminate violence against women from the continent. But a treaty is not enough without measures to ensure effective implementation of its provisions domestically and internationally.