When a national oil company buys acreage in another country, it is more affair of state than commercial deal.

And so Deputy President Kgalema Motlanthe’s arrival in Ghana last April was not unexpected, with Energy Minister Dipuo Peters, new PetroSA chief executive Nosizwe Nokwe-Macamo and others in tow.

There, Motlanthe spelled out the rationale for PetroSA’s purchase of Sabre Oil & Gas, the co-owner of producing assets off the West African nation’s coast: “We hope that these efforts will … improve long-term security of supply to South Africa and guaranteed demand for Ghananian oil.”

Invoking the memory of Ghanaian independence champion Kwame Nkrumah, he toasted that country’s role in “upholding good governance in Africa”.

Murky

But the oil business is a murky business. Discontent was bubbling to the surface at PetroSA over the way the outgoing acting chief executive, Yekani Tenza, and new oil and gas ventures head, Everton September, had managed the acquisition.

Sabre had a small but significant stake in two oil-exploration blocks which were straddled by a significant find, the Jubilee field, producing a steady flow of crude oil.

To gain access to these assets, PetroSA bought Sabre lock, stock and barrel. The company is registered in the British Virgin Islands, a secrecy haven, meaning the precise identity of the sellers remains unknown. AmaBhungane could not track down representatives for comment.

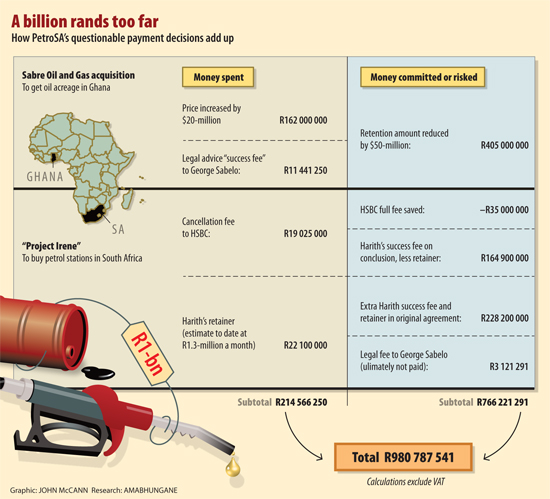

Two matters in particular troubled some PetroSA staff: How Tenza and September had “negotiated in reverse” at final negotiations in London after PetroSA’s project team of experts had left, acceding to a more expensive and risky deal for PetroSA than initially contemplated; and a R11.4-million “success fee” paid to lawyer George Sabelo, whom Tenza had brought to London.

The deal

The deal to buy Sabre became concrete in November 2011. PetroSA composed a project team of specialists to pursue negotiations, first in Cape Town and the next month in London.

Team member Alison Futter, PetroSA’s group tax manager, blew the whistle in an internal memorandum. Chief internal auditor Crystal Abdoll later reported substantially the same to board audit committee chair Nonhlanhla Jiyane, who resigned in protest, writing that “I wish to dissociate myself” from this and other transactions.

Futter wrote: “The final negotiations were held in London in the week 12-14 December 2011. The acquisition price negotiated for Sabre Oil & Gas Holdings by the project team at their point of departure from London was $480-million and a retention value of $160-million.

“Everton September and Yekani Tenza joined the project team in the last day of negotiations and … private discussions were held with Sabre to which the project team was not privy.”

After the project team left, she wrote, the “agreed acquisition price” was increased by September, Tenza and Sabre’s representatives from a basic $480-million to $500-million. And the amount from that to be retained in escrow between the parties pending resolution of tax and other issues decreased from $160-million to $110-million. These were the amounts in the final purchase agreement Tenza signed.

The difference was significant. The higher basic price of $20-million comes into its own in rand terms — R162-million. And the $50-million (R405-million) decrease in the retention, putting a huge extra amount instantly in the sellers’ pockets while exposing PetroSA to massive extra risk, were significant unresolved liabilities to realise.

Denials

PetroSA corporate affairs head Kaizer Nyatsumba this week defended these less favourable terms, saying the board had, in fact, approved a potentially higher amount, that September’s authority stemmed from the fact the project team reported to him, and that Sabre had demanded the increase.

“Having considered Sabre’s demand and the reasons behind the demand, PetroSA’s then acting chief executive agreed to $500-million plus contingencies, which was well within the board-approved transaction price.

The final agreement was a series of compromises by both parties, as typically happens in such transactions. The final negotiated deal was favourable to PetroSA.”

He also said PetroSA had mitigated all potential tax risks.

Tenza this week maintained the $480-million tag the project team wanted was “undervalued”, referring to the higher upper limit the board had approved.

“The project team did not have the authority to discuss that [price]… Before we signed, Everton September … called me and said they [Sabre] wanted more. I came to the offices and Sabre explained its reasons for the increase.”

Among these, he said, was that there had been another confirmed oil discovery. “It was still a good deal.”

The discovery Tenza appeared to refer to was announced only about three months later, at which point the details remained sketchy.

As for reducing the retention, Tenza said that he had conferred with Ghanaian tax authorities at the time, who apparently confirmed a reduced tax liability. “My decision was based on this.”

Enter George Sabelo

Sabelo’s success fee caused equal consternation.

PetroSA’s policy for contracting outside legal advice is to use firms on a panel selected by open tender. All appointments are to be approved by the legal department.

In her memo to the board audit committee chair, chief internal auditor Abdoll stated that the legal department had appointed law firm Webber Wentzel to review the Sabre purchase agreement and perform related services during the negotiations in November and December 2011.

However, “based on interviews with various members of the project team, it would appear that when final negotiations were under way early in December … the team became aware that a lawyer, Mr Sabelo, had been appointed” by Tenza.

Abdoll wrote that her information was that Sabelo first had sight of the purchase agreement when he arrived in London and only joined negotiations at the end of a session two days later, presumably as September and Tenza took over from the project team.

Abdoll made it clear that she regarded Sabelo’s appointment as irregular: his then firm, Farber Sabelo Edelstein (EFS) , was not on the panel, he had no specialist skills, the legal department was not consulted, and his R11.4-million fee was wasteful.

The work he had done, she suggested, consisted largely of subcontracting international law firm Maitland to check the purchase agreement from an English law perspective.

AmaBhungane understands that Sabelo paid Maitland roughly R1.5-million, a fraction of his fee.

Stranger still

What makes Sabelo’s fee extra strange is that it was structured as a success fee, paid as a percentage of the entire deal value.

Indeed, lawyers sometimes work on contingency, being paid a significant percentage to compensate them for the risk of no pay in case of

failure.

But Sabelo had little risk — and earned hugely more than he would have on a daily rate.

But what if the intention was never for Sabelo to keep the money; that he was to pay a large part onwards to one or more recipients not entitled to it?

Sabelo, who has left the law firm, failed to answer detailed questions.

EFS partner Barry Farber said on behalf of the firm that he could not answer questions “save to state that our firm was aware of Mr Sabelo’s mandate to act on behalf PetroSA.

Moreover, we believe that all fees and disbursements levied were in accordance with a written mandate received from PetroSA and properly charged”.

Red flag

A source close to the firm said, however, that the firm had retained only a fraction of the R11.4-million.

Apart from the payment to Maitland, a large amount had been paid onwards to a “corporate advisor” specified by Sabelo. The source, who spoke on a non-attributable basis, would not identify the advisor.

The onwards payment is a significant corruption red flag. Sabelo’s PetroSA letter of appointment, signed by Tenza, a copy of which is in possession of amaBhungane, makes it very clear that Sabelo and FSE were entitled to bill PetroSA for “all disbursements”. Why Sabelo would not have billed back these millions to PetroSA remains a mystery.

Denial

Tenza this week justified Sabelo’s appointment outside of PetroSA’s procurement rules on the basis that the matter was “confidential and urgent”, that the board had “lost faith” in PetroSA’s legal department, and that a board subcommittee had approved a prior appointment of him.

He defended Sabelo’s large contingency fee by saying: “PetroSA spends a lot of money paying lawyers using a time-based rate and 99% of the time, they never succeed. I did not want to put the company at risk [of not closing the deal].”

Tenza disavowed knowledge of a “corporate advisor” to whom part of Sabelo’s fee was to be paid, begging the question, again, why Sabelo should allegedly have done so.

MORE ON THIS STORY

* Got a tip-off for us about this story? Email [email protected]

The M&G Centre for Investigative Journalism, a non-profit initiative to develop investigative journalism in the public interest, produced this story. All views are ours. See www.amabhungane.co.za for our stories, activities and funding sources.