The outcome of the ANCs long-awaited KwaZulu-Natal conference was a win for the Thuma Mina crowd. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

Trade and Industry Minister Rob Davies moved to reassure South Africa’s European trading partners this week that they would not lose the fundamental protections provided by bilateral investment treaties when proposed foreign direct investment legislation replaces them.

But experts warned that, although the motive to review these agreements is sound, the broader trajectory of South Africa’s political economy has European investors understandably concerned.

These include developments in the mineral sector. Major changes are proposed in the Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Amendment Bill, which is currently before Parliament.

Among other measures, it proposes compulsory mineral beneficiation and restrictions on mineral exports.

Peter Leon and Jonathan Veeran, partners at the law firm Webber Wentzel, argued in Parliament recently that these changes might violate South Africa’s obligations under bilateral investment treaties (BITs), and the protection against arbitrary deprivation of property, afforded under section 25 of the Constitution.

The department of trade and industry is reviewing the bilateral investment treaties, many of which were signed before 1996 and the advent of the Constitution.

Designed to attract foreign investment

The treaties, concluded mainly with European countries, were designed to attract foreign investment and protected investors against measures such as expropriation at a time when South Africa’s constitutional framework was still being decided.

Many carry clauses that protect investors’ rights for between 10 to 20 years after the expiry or cancellation of a treaty.

Last year, treaties with some European Union countries, including Belgium and Spain, were left to expire, alarming other European trading partners.

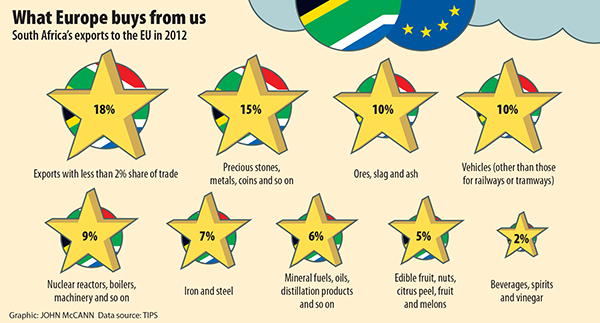

The EU is South Africa’s largest trading partner, accounting for 21.3% of our trade in 2012, according to EU data.

“It is important that government enters into consultations with its main investment partners … about how to best handle the matter in the near future, with a view to minimise the impact of this question on the investment climate in South Africa and on South Africa as an investment destination,” Axel Pougin de la Maisonneuve, head of the economic and trade section for the EU delegation in South Africa, said.

But Davies told the Mail & Guardian that the treaties have “done what was expected of them” and the government’s approach would be to let them lapse when they expire.

"Modernising and updating"

They will be replaced by a more comprehensive framework, outlined in the Foreign Direct Investment Bill, which will be “built on the principals of the Constitution, but will provide greater clarity to investors about the rights and the protections they will enjoy”.

“There is no way that we are doing anything other than modernising and updating our investment protection regime,” Davies said. “We are not removing fundamental protections for foreign investors.”

The drafting of the Bill is “quite advanced” and within the next month the department would put something to the Cabinet before seeking public comment, said Davies.

There is no correlation between the treaties and foreign direct investment flows, he said.

Substantial trade relations were flourishing with countries such as the United States and Japan without a bilateral investment treaty.

Peter Draper, a senior research fellow at the South African Institute of International Affairs, said many of the earlier treaties entrenched problematic investor-state dispute settlement processes.

Major problem

A major problem with them is that they place decision-making powers outside the country in the hands of international panels, whose determinations can have major implications for domestic policies, he said.

“Those processes are conceivably useful where a country’s domestic legal and juridical systems are suspect … but that situation does not apply to South Africa,” he said.

Other countries such as Australia refuse to countenance investor-state dispute settlement in their bilateral investment treaties for the simple reason that their courts are more than capable of enforcing domestic laws.

But Draper said he is concerned about how the process is being handled, the broader trajectory of South Africa’s political economy, and what the Bill will ultimately say.

There is “plenty in the evolution of South Africa’s broader economic policy environment for foreign investors to be concerned about, particularly those operating in the minerals sector, but also those interested in land acquisitions and use, and more general concerns about [broad-based black economic empowerment] policies”.

There is little evidence that the treaties are material to decisions about foreign investment, he said, except for Germany.

SA’s most important trading partner in the EU

Some of its states require bilateral investment treaties to be in place before granting investment risk insurance.

Germany is South Africa’s most important trading partner in the EU, accounting for 20% of exports to the union, according to data from Trade and Industrial Policy Strategies.

The chief executive of the Southern African-German Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Matthias Boddenberg, said the chamber is “firmly convinced that the existing bilateral investment treaty between South Africa and Germany has created a safe investment environment for investors from both countries”.

But given German concerns over the direction of the domestic political economy, their “preference for rules-based approaches to solidifying important economic relationships becomes even stronger”, said Draper.

Davies said these concerns will be evaluated and government is “prepared to talk”.

He did not want to comment on the changes to the country’s mineral rights regime, which are being considered, as this was subject to parliamentary deliberations.

But “no piece of legislation will pass muster unless its constitutional”, he said.