Have I thought of learning isiXhosa? I am learning isiXhosa! I've been learning isiXhosa since 1984! Unfortunately, the only purpose for which I am practically equipped to use isiXhosa is asking bhuti at the petrol station to fill up my car with 93. And khawukhangele umoya (check the tyres). And I could probably buy a bag of weed, too, theoretically. Probably from the same petrol attendant.

The reasons I speak it so badly are probably the same reason my Afrikaans has atrophied into a barely useful relic of my bilingual days at Laërskool Lorraine. Most second-language English speakers are great at English. So what would be the point of us hacking along with my crap Afrikaans, or my even worse isiXhosa, when we can have a stimulating conversation in excellent English!

I once worked with a lady for eight years before I even realised she was Afrikaans-speaking. Eventually I overheard her talking to her sister on the phone in vlot (fluent) – and rather sexy, I'm not gonna lie – Afrikaans. I was aghast. "What? You're Afrikaans? Why wasn't I told?"

She said: "Ja, why not? My name's Natasha Deyzel. Didn't you ever think I might be Afrikaans?"

I said: "No! I thought you were just one of those Afrikaans people who speak English."

"I am!" she shrieked. "But that doesn't mean I'm not Afrikaans!"

I had to shake my head. Yet another case of where I blow my own mind with my oblivious, lifelong racism.

Ukukhumsha

With black people, my preconceptions dictate that they probably are second-language English speakers. But again, they are such old hands at it that their facility with the language of Shakespeare and Churchill and Cleese is no different to mine.

The word Xhosa people use for speaking English is ukukhumsha. Lord alone knows what the provenance of that word might be. When I marvelled at how strange it was that the word for speaking English bears no resemblance to any English words, my wife retorted: "But it's not an English word. It's a Xhosa word, about people speaking English."

This implies for me that speaking English is not done out of love or admiration for the magnificent, malleable English tongue. It's a tactic, a skill, a strategy.

The Xhosa have probably been khumsh-ing since the late 1700s, when British traders first ventured into the land of Ngqika – which is to say, Xhosas have been speaking English for as long as it's been practical.

I like to imagine that the word khumsha has something to do with the high commissioner of South Africa in colonial days. He would certainly have spoken English, being as pale as the driven snow and from England.

So the Xhosa have been khumshing, the Afrikaners have been praat-ing rooinektaal (speaking redneck language) and we English speakers have smugly expected them to. The result is that we are now culturally handicapped.

Race sceptic that I am, I believe that one reason white people eschew exclusively black company is because we would have no idea what was going on. Our language abilities are so poor that we've become social paraplegics, no, quadriplegics.

People's function

If we ever end up at a real "people's function", we either stand blankly at the back of the room, or we end up ruining some poor black guy's evening by having him stand translating into our ear everything that's said like we're Nikita Khrushchev on a state visit to Hollywood.

Conversely, most black folks are amply equipped to function in an English-only environment – that's what the South African workplace is these days, anyway. So they, at least, get to experience the entirety of South African culture, with the possible exception of the odd braai in Pretoria West and committee meetings of the Orania Golf Club.

Ironically, the dominance of English has ghettoised us English cats. Our language rules the economic and media mainstream, but that's all we have access to. Venture outside the big cities and you better speak vernac or you're stuffed. Afrikaans will at least get you somewhere, being the language of the farm and all. But you don't want to be the only Engelsman in Prieska. I know, because I have been that oke.

But we stay in our tiny urban comfort zones, secure in the belief that that's all there is worth knowing. After all, that's all the English-language media ever tell us about. Many people live out their lives in these little enclaves.

I'm convinced we're doing ourselves a massive disservice.

There is an old lyric by the South African punk-rock band Asylum Kids about being a man in a bathroom but living in a bathtub. In a similar way, perhaps one reason us whiteys don't learn any vernac is because of the self-fulfilling belief that there's nothing to suit our First-World, contemporary-sophisticate, internationalist tastes in black culture.

The other reason is that African languages are bloody hard to learn. Not impossible, though. And not as hard as Thai, I'm told.

I'm convinced it's not the language itself but the accent. After decades of rocking the whole "Molo, unjani, ndiyaphila, enkosi [good morning, how are you, I'm fine, thanks] preamble, the bottom still falls out of my world the minute we get the introductions out of the way and the person starts actually speaking isiXhosa to me. The accent of spoken isiXhosa makes it hard to follow and I start getting pulses of embarrassment as I lose the thread of the conversation.

Learn isiXhosa-quality isiXhosa

I have to come with the "uxolo andiva, ndiyazama ukufunda ukuthetha [sorry I can't hear you, I'm still learning to speak]" and then we lapse into English. Because, as we said, their English is guaranteed to be better than my isiXhosa.

Whip out your Learn isiXhosa-quality isiXhosa and you'll soon be unmasked as a beginner. And try not to pretend to be anything but that, otherwise you'll look like a wannabe Johnny Clegg, fake-vernac-speaking poser.

So unless you're just greeting someone in passing, best not even to bring up the fact that, "actually, I know a bit of isiXhosa". Just leave it in the boot, as it were.

Perhaps the odd word that you've picked up from watching Live Amp or Tsha Tsha or listening to Thandiswa Mazwai will help you to follow some vernac conversation without requiring a translator.

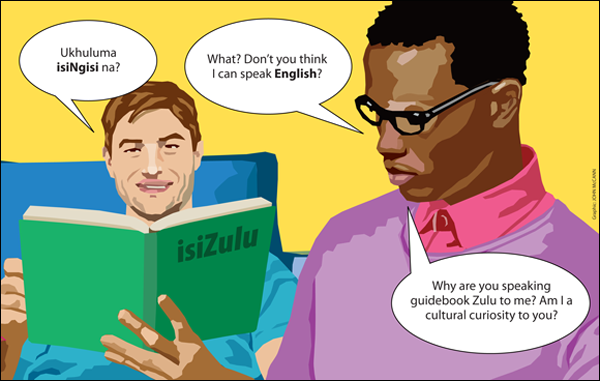

There's also an interesting irony to some black people's attitude to white vernac speakers, particularly in the city. Some people will love it when a white person speaks good vernac. But they hate it when you speak crap vernac. Trying beginner isiZulu on them will seem condescending. You get this look like, "What? Don't you think I can speak English? Why are you speaking guidebook isiZulu to me? Am I a cultural curiosity to you?"

By contrast, if your isiZulu is polished and tight, men will welcome you like a brother and women will melt into a rippling puddle of lust at your feet. But quite how you're supposed to get from the frowned-upon crap vernac to the lauded "fluent vernac" has never been explained to me.

I sometimes think the only way to really rock the vernac is to have it found in your mouth, as they say. You need to grow up speaking it. So the same guys who grow up on the farms, those country bumpkins in the two-tone farm shirts and shorts, those are the guys who understand African languages.

Cultural curiosity

My mate OR is a white guy who grew up on a farm in the Eastern Cape. His first language was Sesotho, after which he learned isiXhosa. Only when he turned five and began attending school did he pick up English.

OR can order a Black Label at a bar and within seconds he'll have the entire staff complement in the palm of his hand. Women… ag, don't get me started. He has to fend them off, or change back to English to save his modesty.

Another cultural curiosity I've noticed is that the white guys from the rural areas who speak decent vernac often display a set of political attitudes way out of step with neoliberal, big-city values.

It's not impossible to hear a clanging K-bomb from the mouth of your uncle who grew up in the Kei among the people and ran a trading store all his life. Try calling him on it and you'll be told you don't understand.

That's right. I don't understand. What I do see is that these rural white dudes are past any notions of the noble savage, of patronising accommodation of their black brethren. They do not fetishise African culture the way us city dwellers are prone to, us with our arts degrees and couple of weekends in the township with Habitat for Humanity.

The white man in Africa – I mean the white man in real, rural Africa – seems to be content in his understanding that he is not black. He is a member of a particular tribe, a white tribe of Africa. He can learn the local lingo, understand many of the customs, but he's still of another tribe, and proud of it. He has found isi-Xhosa in his mouth, or learned to thetha when he moved to the country the same way the amaRharhabe learned to khumsha when it was practical.

Maybe these people actually have a better grasp of race relations than we bleeding-heart, Democratic Alliance-voting, Daily Maverick-reading, black friend-having, integrated nightclub-rocking city liberals. Maybe they do. But they also have a helluva difficult time fitting into the big-city vibe – unless they're able to bring their rural network to town with them.

Fistful of websites

I didn't grow up in the country but I'm descended from people who did. Within my lifetime, I've watched my mother lose her isiXhosa. She grew up in Port St Johns working at her dad's petrol station. Then she moved to Port Elizabeth to work and, within a few decades of disuse, her isiXhosa vocab had pretty much disappeared. She retained the ability to understand it but, like her son, she plays this one close to her chest.

Having witnessed this, and with a black wife proudly rocking my surname in her Twitter handle, I'm determined to do better. In the course of my spurious lifetime here in Southern Africa, I will at least gradually be able to speak a bit more African as time goes by. Not less.

I currently own eight isiXhosa phrasebooks, dictionaries, CDs and personal notebooks. Besides that, there is a fistful of websites I frequent and a first-language isiXhosa speaker on Twitter on the couch here who at the drop of a hat will explain the spelling of ukuqhanqalaza, if not where the word comes from. It means "to protest", by the way.

So I should be able to improve at the very least. Whether I'll ever be fluent remains to be seen, but we live in hope.

This is an extract from Marrying Black Girls for Guys Who Aren't Black (MFBooks/Jacana), on sale October 24. Visit Hagenshouse.com