A NATIVE OF NOWHERE: THE LIFE OF NAT NAKASA by Ryan Brown (Jacana)

The seldom-practised discipline in South Africa of writing literary biography now brings in this much-lauded record of Natha-niel Ndazana Nakasa (1937-65). He was the bumptious, undersized youth who thrashed the famous Drum magazine literati of the Fabulous Fifties and who founded the literary quarterly The Classic. This ran for all of three issues under his editorship, designed to promote the burgeoning African literature, before becoming a showcase for “whities” like long-lasting Athol Fugard.

Perhaps Nakasa is best remembered by his contemporaries as the first-ever “black” columnist to tell it like it was, week after week, in the Rand Daily Mail. There Nakasa introduced non-black South Africans to rackety penny whistles and pangamen, dagga smoking and the dompas.

Yet as the Fulbright-fuelled author here, Ryan Brown, seems unaware – and as Chabani Manganyi warned over 30 years ago – devising such biographies at all tends to be a somewhat elitist Western exercise in terms of audience and subject matter. By contrast, “life writing” is rather more appropriate for such a maverick huckster.

Note that Nakasa himself devoted his brief life to punching against such starchy canons.

Whereas Brown’s exemplary trawl of the available printed records, imperfect as they are, and of wide-ranging interviews during her stay- over in Johannesburg and of the obscurest archival sources will feed the slow-moving harem of scholarship for decades to come, perhaps more footwork than footnotes was called for.

For example, how come this researcher did not pick up, analyse and interpret Nakasa’s own description of himself: biologically Pondo, by habitat Zulu and strictly English-speaking?

Why does she not note that his birthplace of Durban, which she goes on and on cutely calling a “sleepy coastal city”, was actually a British colonial backwater? Surely there he was taught to be everything his class and colour prevented him from being.

A reminder here that Alan Paton’s Cry, the Beloved Country was first published in 1948, which was before all that dreadful mental pellagra of Bantu education and so on, which she so melodramatically and repeatedly decries, came in. So there.

Then, once her tennis-playing joker escapes to the imperial capital, for all of his London stay she has only half a sentence to spare. Not a mention, for instance, that crucially there he meets up with Essop Patel, who undertakes to preserve Nakasa’s reputation. This he accomplished by compiling selections of his work, initially in the reading room of the British Museum.

Although dear Judge Joe [Patel] should never have snipped out all the fiery bits, which he did so as not to antagonise the censors back home, Patel’s three increasingly elaborated editions of The World of Nat Nakasa (1975, 1985 and 2005) served to keep Brown’s subject viable for her own project.

Once Nakasa had escaped on an exit permit to Harvard to study journalism (not postcolonial politics) Brown should be more on her home ground. But once more a query arises: Why did she miss the long, award-winning story called The Exile, published in the Massachusetts Review in 1970, which summarises all the memorialising tugs about our Nat?

There he is, cadging and bendering his way through that late bourgeois world, driving his career into a blocked termination. South African-born author Rose Moss tutored those Nieman fellows in the local law school for years and knows precisely what boxed Nakasa into utter, dead-end despair.

From putu pap and pata pata then, he had come to face the world’s best-educated academics. And they stonewalled him. By decrying the injustices of elsewhere, as one of his activist friends remarked – and Brown omits – they apparently released themselves from dealing with any of their own disgraces.

So no Manhattan Brothers or Jazz Maniacs were swinging for Nat by then. Meanwhile others of his liberal circle back home, like his Drum editor Tom Hopkinson, who detested the demon alcohol of those degrading shebeens, was going on to a knighthood, and his beehived contributors (Nadine Gordimer, Doris Lessing) were heading for Nobel prizes.

Then, in 1965, James Baldwin, who by the way had also contributed to The Classic, was by no means buried yet alongside Nat Nakasa and Malcolm X in Ferncliff Cemetery outside New York City. After being offered only tea by the Kennedy brothers, who thought the Civil Rights Movement had not much to it, Baldwin had also been driven into exile, with his bestselling Another Country as the reason why.

Brown should rather have noted that, while Nakasa was disappointed not to encounter Baldwin in the Harlem district Sophiatowners like himself had so emulated, down to the two-tone shoes, he most certainly was aware of the latter’s fictional liberation hero.

Having run his rhetoric dry, drained his drams and plugged every available vaginal opening, the fictional protagonist had arrived at his only way forward – which was to jump out of a high-rise, graphically described.

Hence Nakasa’s final plunge was a literary copycat act, a reversal of that King Kong myth of raging black horrors scaling skyscrapers. As the brawler after whom the musical King Kong was named had demonstrated, sometimes the only way to show a life was one’s alone was to end it. Nakasa’s dive was intended as a protest against yet another culture that had not allowed him any way to survive.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Central Intelligence Agency closed their files on their stumpy, stateless refugee corpse, his visa having expired. But Brown should not have closed hers. The interrogation of his appalling exit she offers serves only to make it look ever more blameless and bland. He merely “died from a fall” then, as the euphemism in the latest World of Nat Nakasa has it.

A further detail apparently beyond Brown’s remit is the point that in 1982, when the local African Writers Association revived Nakasa’s The Classic, they put his only known short story into print for the first time. So possibly the cultural scene here was never as shut down as Brown would like us to suppose.

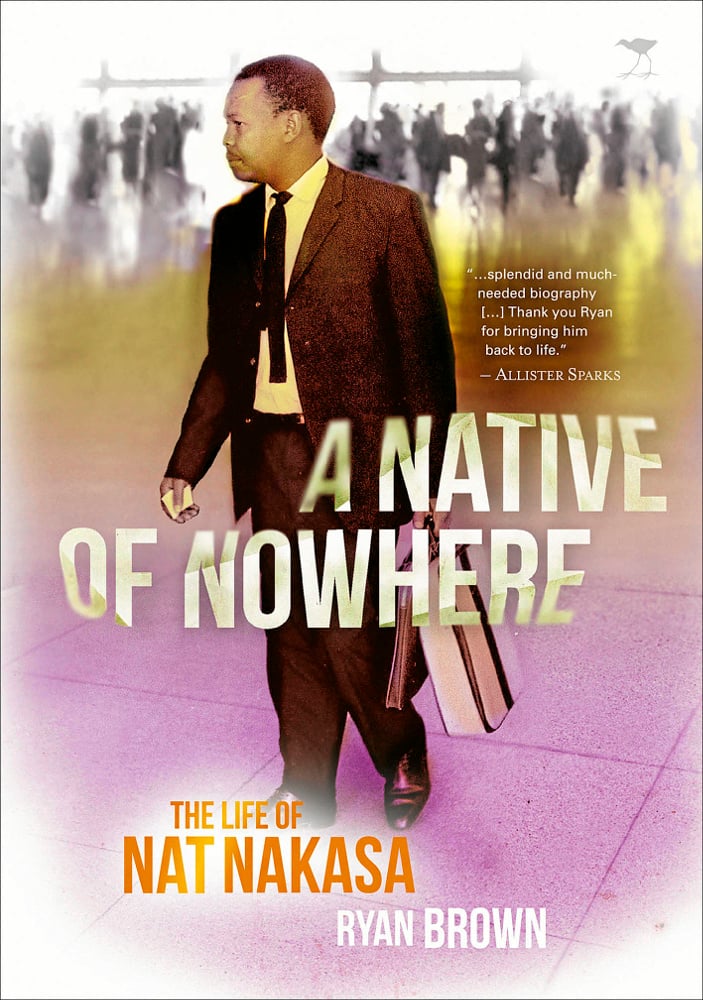

Her publishers, Jacana, could also have chosen better than to encase Nakasa’s image on the cover in pink and to have decapitated him on the spine. After all, when he hit the sidewalk after flying seven storeys, his blood exploded red. Like anybody else’s.