The 8 000-strong congregation has its hands up in the air, waving them rhythmically in unison, hallelujah style. Enchanted. Enthralled. Enraptured. This is Sunday night in Bellville, north of Cape Town. Here in the Church of Bruce Springsteen you come for rock 'n roll redemption. And even if it is temporary, it is real at this very moment.

"Good evenin', good evenin'! Good evenin' Cape Town! Good evenin' South Africa!" the little showman/priest cranks up the Holy Roller – the holy rock 'n roller – shtick. Going Southern Baptist one word short of "y'all" and soundin' like Jesse Jackson at the famous Wattstax soul festival back in 1972.

He pauses dramatically. This church is loud – the cymbals are getting a beating, the flurry of jazzy organ notes echoes him, the crowd's mouths are 8 000 little circles as they roar back to the five foot nine (about 1.75m) centre of their attention.

Clad in black denim, a charcoal shirt, loosely knotted skinny grey tie and off-black waistcoat, he stands in the middle of the massive stage, his head slightly cocked as he listens approvingly and resumes: "We've come thouuuusands of miiiii-les …just to be here tonight! The mighty EStreet Band has come thousands of miiii-les, 8 000 I think, to be exact" – he pauses and I can almost see the naughty glint in his eyes from where I sit high up in the stands – "to play some place that is just like Asbury Park's Convention Hall [in his home in New Jersey]! This is the same place, I'm tellin' you … !!!"

Tonight the communion wine comes in a big plastic glass from an ecstatic fan and the sweating priest downs it one long gulp. He's refreshed.

"The question is, can you feel the spi-riiiiit?" he sing-pleads. "Can you feel the spirit, nowwwww?" even more urgently. He extols, cajoles, channelling the spirit of his hero, James Brown.

His three backing singers, who clearly learned to sing in similar Southern choir stands where Aretha, Etta and the Reverend Al Green were taught, sound like a 100-voice choir as they respond to his repeated calls: "Yeah, yeah, ye-aaahhhh!"

It is exhilarating stuff.

In his book Hungry for Heaven, published back in 1988, author Steve Turner said that the former Catholic altar boy was the first rock 'n roller "to show he fully understood the redemptive theme" of religion by taking "the premise of alienation and deliverance and embellishing it with biblical language".

Quite coincidentally, in the same year I joined a bunch of young South Africans on the trek to Harare for Amnesty International's Human Rights Now! concert, which featured Springsteen, Peter Gabriel, Tracy Chapman, Youssou N'Dour and Sting.

Our bus broke down halfway between Beit Bridge and the Zimbabwean capital. The concert had already started when we arrived. We ran into the stadium as Gabriel's opening notes of one of my favourite songs of the time, Biko, rang out.

I was already a fan of Springsteen's, having bought his albums Born to Run (1975) and The River (1980) when they were first released, but he completely converted me with his performance, including a great speech (courtesy here of an article Rhodes University academic Richard Pithouse recently wrote about Springsteen) that felt as though it was addressed to me directly.

He said: "I guess there's a lot of young guys out there that are conscription age for the South African army … I guess there can't be much worse than living in a society that's at war with itself … under a government at war with its own people and being required to support that government … and I just wanna say to all young South Africans that I do not envy your position … my prayers are with the young men here that you can use your hearts and voices in the struggle of the dignity and freedom of all the African people … because whether it's the systematic apartheid of South Africa or the economic apartheid of my own country, where we segregate our underclass in ghettos of all the major cities … there can't be no peace without justice and where there is apartheid, systematic or economic, there is no justice … and where there is no justice, there is only war!"

He burst into Edwin Starr's dramatic soul classic, War: "War, huh yeah! What is it good for? Absolutely nothing!"

And I became a believer in Bruce Almighty, right there under the Harare moon.

But, as they say, time and other things happen. Not to mention Springsteen's not-too-good artistic run in the 1990s, even acknowledged by him.

"I didn't do a lot of work," he told Rolling Stone in 2009. "Some people would say I didn't do my best work."

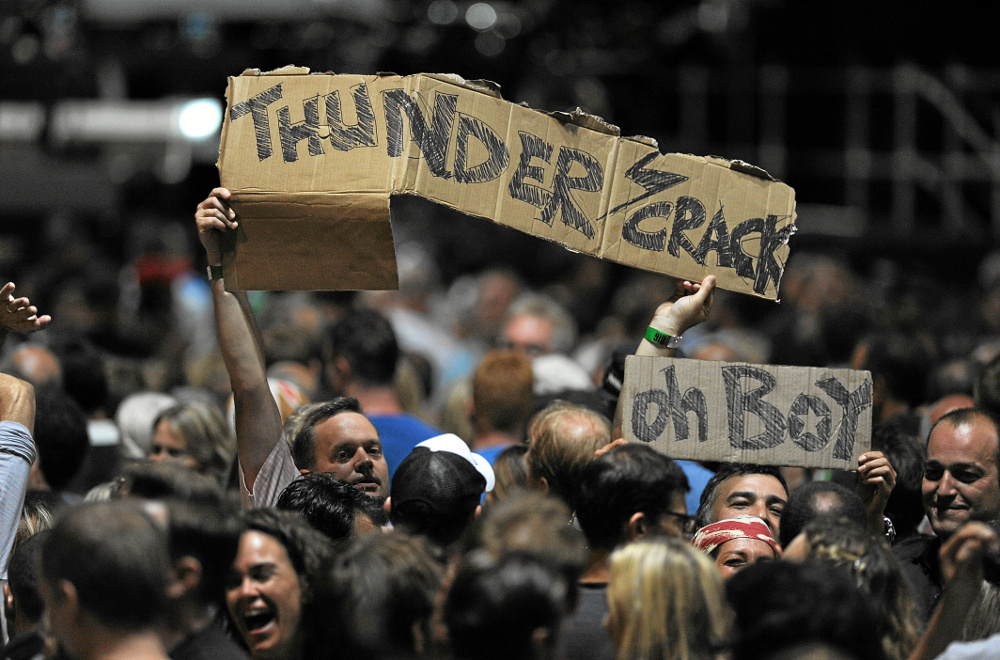

Springsteen's Fans Photograph by Halden Krog, Gallo Images.

Springsteen's Fans Photograph by Halden Krog, Gallo Images.

So when Springsteen and the E Street Band allows 45 journalists into the end of their sound check before Sunday evening's show at the Velodrome in Bellville I am at best still a Bruce agnostic – and only because of his/their brilliant first six albums and some fine tracks on more recent records.

With the sound check over, Springsteen settles on a sound monitor on the edge of the stage, with us hacks looking up at him from the venue's golden circle. He is 64, but unlike in the Beatles song, he is not wasting away.

His hairline is slowly receding, but he is still a really handsome man because, as New Yorker editor David Remnick wrote in a 2012 profile: "If one had to guess, he has, over the years, in the face of high-def scrutiny and the fight against time, enjoined the expensive attentions of cosmetic and dental practitioners."

A tight black T-shirt shows off the success of "more or less the same exercise regimen for 30 years: he runs on a treadmill and, with a trainer, works out with weights," Remnick wrote. "His muscle tone approximates a fresh tennis ball."

In his right ear he has a tiny diamond stud, in his left a minute silver cross, and on his right wrist is a bangle of big sky-blue beads.

"What can I do for you?"

Springsteen knows how to work an audience, even a small, sceptical, jaded one like this. The questions flow, the answers come, punctuated with laughter, smiles all around and iPhones recording every utterance.

I ask if he thought the economic apartheid in the United States he referred to in his 1988 speech has gotten worse or better. He looks me straight in the eyes as he answers: "There is a tremendous problem with income inequality in the States right now and it's been increasing and increasing.

"Eventually it tears society apart and I don't think society can make good when economic differences and economic inequalities are so widespread. It is a real problem in the United States and I know you guys have big problems here too."

After 20 minutes his media minders say enough – the journalists wander off to the hospitality tent, completely mesmerised.

Sunday night's show was the first of Springsteen touring his latest, and 18th, studio album, High Hopes, which is already at number one in the US and the United Kingdom.

As Harry Brown wrote in Counterpunch magazine, it consists "mainly of cover songs and previously unused ‘old' material, [and] is by no means a highlights collection from the last 19 years, a setting out of the Gospel According to Bruce".

"It's more like the Apocrypha, the bits left out previously because they wandered away from the canonical message of a particular moment. But together on this new record, these apparent detours and meanderings demonstrate the fundamental unity of his approach and concerns over this period, and demonstrate too the general excellence with which he has turned them into songs."

Many of the High Hopes songs are included in his 27-song, three hours-plus set.

Over the past two decades Springsteen has moved from musical vignettes of working-class life to campaigning for working people's rights, albeit in a poetic fashion.

Always progressive, he has moved even further to the left. Musically he has also moved from predominantly heartland rock to include a lot more soul and gospel, as well as roots music.

"Did you hear what I heard?"

Before launching into a barnstorming version of the haunting mariachi-Irish rebel song We Are Alive from 2012's Wrecking Ball, Springsteen says how "humbled I am to be here in the land of Mandela. We're here because of his grace."

All 17 people on the stage are playing as if their lives depend on it. And then Springsteen changes the lyrics to reflect on the Sharpeville massacre of 1960. Even more astonishing, in the next line Springsteen also changes the lyrics to talk about the Marikana massacre.

Sony's Duncan Sherwell, sitting next to me, nods. "Yes, that is what Bruce sang!"

This is a musician who actually notices where he has landed when he goes on a world tour. I guess one can say with safety there's not a single Republican on that stage.

A new addition is the phenomenal guitarist Tom Morello, who was formerly with left-wing rap-rockers Rage Against the Machine. Dressed in olive-green fatigues, Morello has a sky-blue guitar with "arm the homeless" painted in bold red, with a hammer-and-sickle sticker next to the bridge. Morello makes it howl, scream; he makes it rage against The Man, against the machine.

By encore time, Springsteen has gotten rid of his waistcoat, the tie, the shirt, and is down to a dark T-shirt, soaked in sweat. But he's not stopping.

"Think of it this way: performing is like sprinting while screaming for three, four minutes," Springsteen told Remnick. "And then you do it again. And then you do it again. And then you walk a little, shouting the whole time. And so on. Your adrenaline quickly overwhelms your conditioning."

He is using encore time for a slick run-through of the crowd-pleasing greatest hits, Born to Run, Dancing in the Dark and Born in the USA, plus live staple Shout. Over the three and a bit hours the rock 'n roll pastor has seduced us, he has conscientised us; now he makes us dance, dancing in the dark.

For now, even if it is just tonight, with all the madness in our souls we're all believers in the Church of Bruce.

Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band are playing at FNB Stadium in Johannesburg on Saturday night.

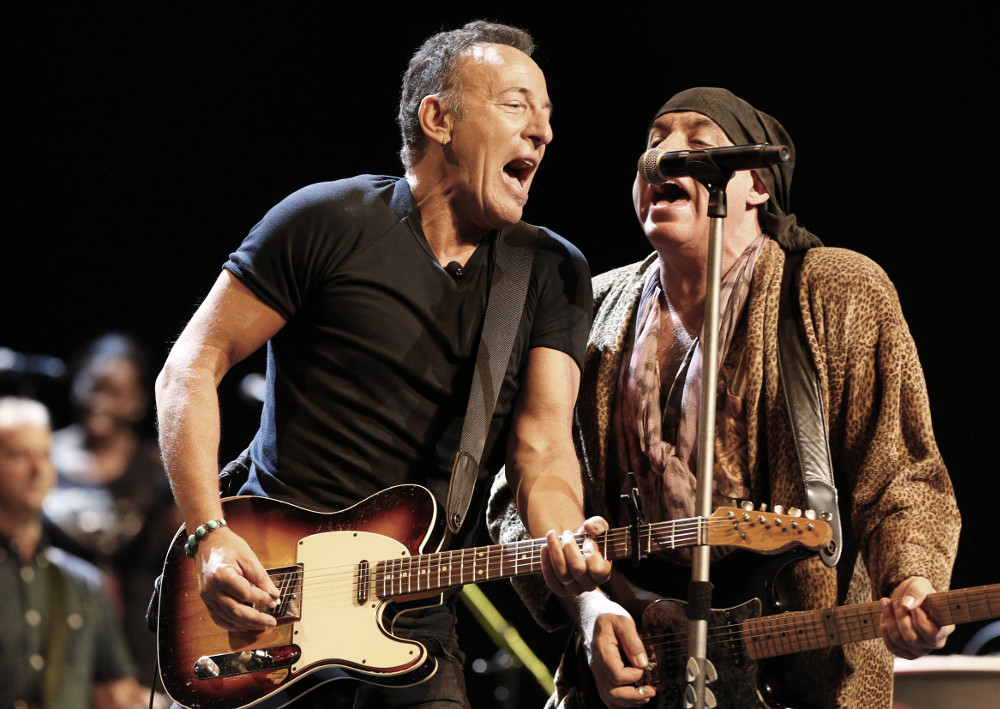

Springsteen and Steve van Zandt. Photograph by Mike Hutchings, Reuters.

Springsteen and Steve van Zandt. Photograph by Mike Hutchings, Reuters.

Sopranos star recalls his Mandela moments

Little Steven van Zandt, Bruce Springsteen's friend of 50 years, his wingman on guitar in the E Street Band, a musician in his own right, a successful radio DJ and an effective decades-long campaigner for progressive causes, is talking seriously to three South African journalists about the effectiveness of the cultural boycott against the apartheid regime.

But all I'm seeing in this small dressing room at the Velodrome in Bellville before the Springsteen show on Sunday night is Silvio Dante, the consigliere to Tony Soprano in the brilliant The Sopranos television series, that Van Zandt inhabited to such chilling effect.

Unlike his toupee in the series, he is wearing a black bandana – but the expressions, mannerisms and inflections are pure "Sil Dante".

If the Boere knew they were messing with the Sopranos they would have succumbed much earlier, I chuckle quietly to myself.

It was exactly 40 years ago that American Van Zandt came to South Africa "to educate myself" on one of 40 international political issues he was examining, he tells us.

As part of Springsteen and the E Street Band, who had just had success with the album The River, "I thought now that I can make a living doing this rock 'n roll stuff, why don't I see what I have been missing for the last number of years … I didn't pay any attention at school so I just decided to educate myself.

"I started with my country's foreign policy since World War II, seeing what we're doing – all these issues, growing up thinking we're always on the right side, we're the heroes of the world [and] finding out that it's quite the contrary. At least half of the situations we're on the wrong side."

There were many "bad, bad people" his country was supporting, but South Africa came up as a sort of "in-between one", with newspapers claiming there were all these great reforms happening in mid-1980s South Africa.

After two trips to the country and after speaking to many people, Van Zandt decided that "apartheid could not be reformed; it must be eliminated". He chose Sun City as the symbol because of the resort's involvement with sanctions busters, created Artists United Against Apartheid and convened 49 artists across a wide range of genres, including Springsteen, Bob Dylan, Miles Davis, Run-DMC, Jimmy Cliff and Gil Scott-Heron, to record Sun City.

The song was not played on radio, but the video got heavy rotation on MTV, conscientising a whole young generation about the evils of apartheid and its homeland policy.

Congressmen's children started asking their parents why they didn't do something – and eventually anti-apartheid legislation was introduced, even with Ronald Reagan in charge.

Van Zandt does not claim that Sun City led to the fall of apartheid – he is way too humble and intelligent a person for that – but believes the groundswell the song caused did have an impact.

"It's a mixed feeling, coming back to South Africa," he says, even though we are 20 years into democracy. "I'm embarrassed [by] what we had to do. I'm not going to stand and be some fucking hero because of my country's bad policies that I helped fix … I'm not the hero – they're the heroes; [Nelson] Mandela is the hero. The biggest thrill of my life was watching him come out of jail."

Van Zandt met Madiba twice, once at Wembley in London and again when Mandela was doing a fundraiser in the United States.

"I never met anybody like him. It was not like meeting a politician, a revolutionary … He was like a religious leader, like old-time religious leaders, like the Buddha, John the Baptist, with the inner strength and warmth. He was powerful!" – Charles Leonard