The proliferation of illegal credit providers is not just a regulatory failure but a symptom of the broader inequalities entrenched in the country’s financial system

Parliament is considering taking to task a burgeoning industry of microlenders that is capitalising on a legal loophole to charge exorbitant interest rates to vulnerable consumers.

Industry experts are concerned that a growing market of lenders is crippling cash-strapped South Africans by charging fees four or five times the legal limit, and that this is undetected by regulators.

The topic has come under scrutiny over the past few weeks as the trade and industry parliamentary portfolio committee has deliberated the National Credit Amendment Bill 2013, which will replace the National Credit Act (NCA) of 2007.

"The concern is those unregulated, unregistered companies dishing out loans," said Kobus Marais, the spokesperson representing the Democratic Alliance in the portfolio committee discussions regarding the Bill. "It's a major market."

Underground operators

Hennie Ferreira, the chief executive of industry body MicroFinance South Africa, agrees.

"The guys who are legal and do their returns and are in the eye of the regulator stick to the terms, I am fairly confident of that," he said. "But underground, there's a burgeoning market. They make up their own rates based on … supply and demand."

The current Act sets out a formula that stipulates the maximum amount of interest that lenders can charge for various types of credit.

It also requires all credit providers with a loan book of more than R500 000 and more than 100 loans to register as a credit provider, which is overseen by the National Credit Regulator (NCR).

But many of the companies guilty of overcharging are small or one-person businesses that do not meet these thresholds and are therefore not required to be registered.

The result is a group of lenders that fly under the radar of the law and are not regulated by industry bodies or the NCR. According to Ferreira, the segment is growing.

Unregistered credit providers

"There are at least 50 000 unregistered credit providers in the country. The guys in the rural areas say there are many more.

"Once, on a trip to rural KwaZulu-Natal, I saw 30 loan sharks in the space of a rugby field. They were operating from their jeans pockets or the boot of their car."

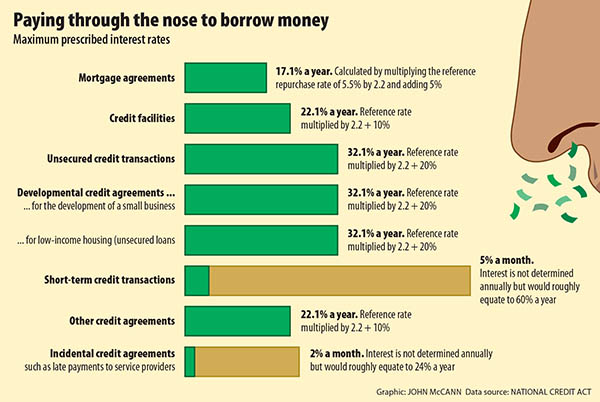

The NCA currently sets maximum allowable interest levels based on the repo rate. Rates change according to the type of credit extended.

The formula multiplies the repo rate by 2.2 and adds a varying percentage depending on the type of loan (see graphic).

According to the Act, the current maximum interest allowed to be charged on mortgage loans is 17.1%, on credit facilities it's 22.1%, and for an unsecured loan, it's 32.1%.

Lenders extending short-term loans cannot derive capital of more than R8 000 from the transaction, and the loan agreement must be for six months or less.

There are also limits on the initiation fee charged, and a maximum of R50 may be charged as a monthly administration fee. But the poor are often the recipients of rates much higher than this, and are thus forced to service high rates of debt they can ill afford.

Although all agree there should be a clampdown against such practices, Ferreira cautions that interest on small loans should not only be viewed as a percentage figure.

"The problem with small loans is when you annualise the percentage charged for interest, it looks horrific," he said.

"I'm not defending them … but it's a comparative thing. If you lend someone one cent on Monday, and he pays you back two cents on Tuesday, you've made interest of 100%, but you've still only made one cent. There's a discussion about affordability [for the borrowers] versus sustainability [for the lenders]."

Change underway

Industry experts agree that it is extremely difficult to gauge the extent to which these businesses are over-charging when they do not fall under a regulatory body. It is unclear whether this so-called loophole will be addressed in the Bill, although the government has indicated its concern.

"Parliament is concerned about the high cost of credit, especially to the poor," said Zodwa Ntuli, the deputy director of policy and legislation at the department of trade and industry.

The department is calling for the Bill to review the various caps on interest. It is not yet known whether they will come as adjustments to current caps or whether they will take a different form altogether.

According to Ntuli, "this is a consultative process and it is not possible to pre-empt the changes".

The department is also calling for the Bill to better police the selling of loan books, something that is common practice among financial institutions.

"There is no intention to do away with the selling of loan books, but when such happens, the obligation must be on the credit provider to make sure that loan book does not include debt that has expired or been written off," said Ntuli.

Transparency has made up for a lot

The National Credit Act (NCA) has been a vast improvement on the law it replaced, according to Angela Itzikowitz, an executive in the banking and finance department of legal firm ENSAfrica.

The Usury Act of 1968, which was repealed and replaced by the NCA in 2005, called for lower terms of interest than the NCA does.

It allowed the repo rate to be multiplied by a third. The NCA calls for the repo rate to be multiplied by 2.2. But the NCA provides transparency that the previous law did not, she said.

"While the interest rate might have been lower under the Usury Act, people used to include all sorts of other peripheral charges — transaction fees, initiation fees, fees for vetting the property, and property insurance was incredibly high," said Itzikowitz.

"Now the NCA is prescriptive about the kinds of charges that can be levied and no additional charges can be added."

The National Credit Regulator has also called for a code of conduct requiring "lenders to subscribe to a code where the credit assessment measures are now far more prescriptive," Itzikowitz said.

Adhering to the code will make lenders less likely to hand out unaffordable loans to consumers.

"I think we are adhering to international best practice," she said. "A number of jurisdictions, such as China, have looked to South Africa when putting their own [laws governing credit] in place."

But some changes being proposed in the Bill, such as the removal of adverse credit information from the records of errant payers who have proved sufficiently that they have been "rehabilitated", are a step backwards, she said.

The Democratic Alliance is in favour of the change, which it believes will give consumers the chance to turn over a new leaf. But the party opposes putting a cap on the interest charged for loans.

DA spokesperson Kobus Marais said: "We're not in favour of over-regulating because consumers must make their own choices. You must disincentivise irresponsible lenders and incentivise people to only buy from registered lenders. The government must promote education [of consumers] … which is easier said than done."