It was mathematics

My very first encounter with God was a vicarious one and it was all because of my grandfather's car. It was twice as long as the vehicle I drive now and black all over. It had round, red unblinking eyes for tail lights and twin fins that jutted aggressively out of the bodywork. What's more, it was American and this to a four-year-old boy in Accra, Ghana, gave it an added cachet. They didn't have separate passenger and driver's seats in those days. It was rather like someone had simply taken two leather sofas out of their living room and fitted them neatly inside the car, one behind the other.

In time my grandfather's car grew old and cantankerous. It refused to start and sat glumly in the yard while we clambered over the seats and spun the wooden steering wheel this way and that until an aunt – why is it always an aunt? – shooed us away. My mother's father, the proud owner of this magnificent Batmobile, was a Methodist priest, the Right Reverend Moses Debrah.

Looking back, it must have been largely due to Reverend Debrah's influence that I grew up in a house where religion loomed so large. My mother would sing hymns throughout the day and together with my father attended every Bible study, leaders' meeting and fellowship group the Methodist Church had on its calendar. So when one day my father in an uncharacteristically jovial mood asked me over lunch what I'd like to be when I grew up, I promptly said: "A priest!" His face darkened and, though he didn't quite say "you stupid boy", I knew I'd said the wrong thing. My mother was pleased, however, and chided my father to leave me alone. But my path was set. I became an engineer. Just like my father. So much for entering the priesthood.

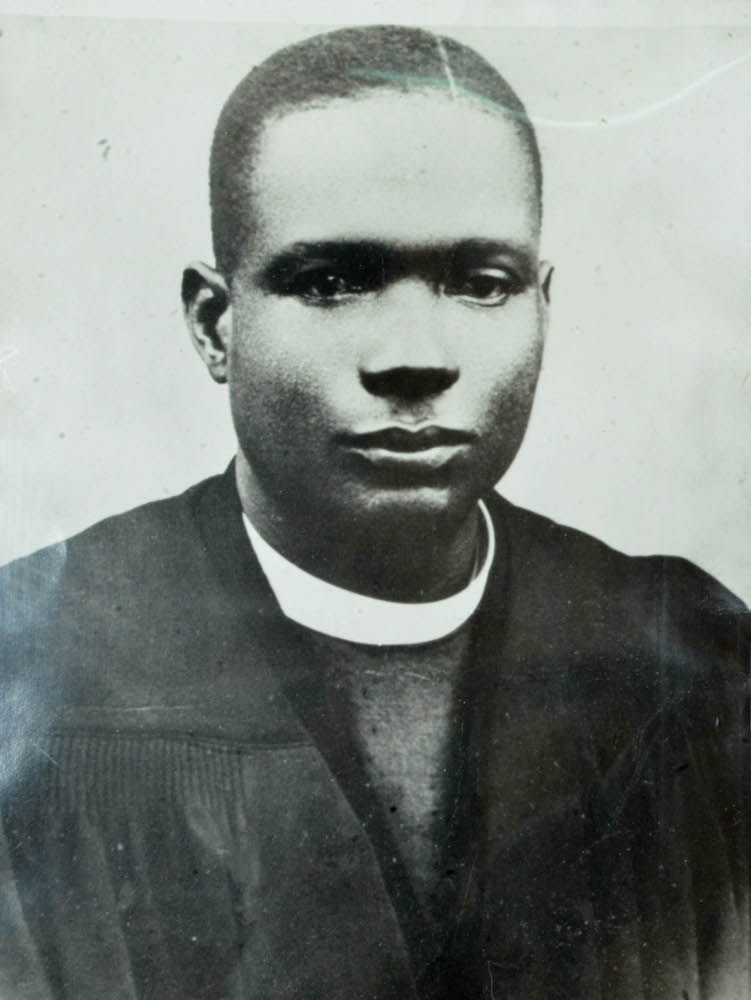

An early picture of Ekow's father, Kodwo Duker.

In the late 1980s I went to the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB), undoubtedly one of the most beautiful campuses in the United States. It sits on the edge of the Pacific Ocean cradled by low hills, with turquoise lagoons snaking through the greenery. I was studying for a master's in engineering at UCSB and took a mandatory course in mathematics.

Although I've forgotten most if not all of the advanced mathematics I studied at the time, I do remember one thing: once in a while when I'd be hunched over my desk, wrestling with arcane equations and even more obtuse formulae, something magical would happen. All of a sudden a breathtakingly simple and elegant solution would emerge and leave me feeling I had witnessed something divine.

Emotive words

Several years later when I started writing seriously, I experienced that all over again. Sometimes I would read a passage – more often than not something someone else had written – and marvel at how such an economy of words could convey such depth of emotion. One word more and the passage would teeter on the edge of verbosity, one word less and the entire meaning would be lost. At such times I felt as if the curtain to a mystical realm had been pulled briefly aside, allowing me to catch a glimpse of something majestic and true.

I graduated from UCSB and, reluctantly, I left Santa Barbara to prospect for oil in the North African desert. In Algeria I'd often drive for a day or more to get from one oil rig to the next, a commute that gives perspective to my daily travel into the Johannesburg CBD.

I can still remember waking up before dawn with the muezzin's call to prayer hanging tantalisingly in the chill desert air. It was a hauntingly beautiful sound, utterly self-assured and yet laced with anguish. And in those brief moments, I felt as if those words, which I did not understand, had somehow opened a pathway to heaven.

Months later two European colleagues were captured and beheaded by Islamic insurgents. That was puzzling, for how could the same God who led the muezzin to cry out so beautifully every morning also inspire other men to murder? I could almost hear my father say: "You stupid boy."

After a decade-long sojourn in the oil fields, I stumbled into banking where I found myself crafting lengthy presentations to explain why equity prices couldn't keep rising forever. This was in the wake of the financial crises, when everything that could tumble did indeed do just that.

Gallant fight

My wife Thando took a tumble too and died after a gallant fight to live. She was exceedingly beautiful and overflowing with an irrepressible zest for life. I proposed to her in a hot-air balloon and we were married in August 2009 on the lawn overlooking the Victoria Falls. She would want me to point out that we got married on the Zimbabwean side of the Falls. Thando was only 32 when she died.

She had a rare condition that meant her body was grimly determined to get rid of its own liver. When she was first diagnosed late in 2010, we were told she had five years to live. Five months later, that estimate had been cut to two years. It was as if someone was holding a stopwatch over Thando and the hands were turning faster and faster.

Ekow Duker married Thando in 2009.

On August 13 2011 – I remember that was the day the Premier League kicked off and we were both rabid Arsenal fans – Thando began vomiting copious amounts of clotted blood. This had happened several times before and indeed was a symptom of her condition. But it had never been this bad. In a frenzy I drove to the hospital in Morningside with Thando passing in and out of consciousness by my side. She almost died that night. Eventually they managed to stabilise her and in the morning one of the doctors – from his accent I think he was Russian – came to me with a proud grin and said: "It was like hole in hosepipe."

Because Thando's liver wasn't working, all the toxins in her body went straight to her head and made her delirious. It was heartbreaking to see the woman I loved having to be restrained in her bed to keep her from hurting herself. I was terribly impatient for her to be transferred to the Donald Gordon Medical Centre, where she'd be on standby for a new liver. I couldn't understand why it was taking so long.

Thando did get to Donald Gordon two days later when a bed in the intensive care unit became available. That same afternoon, the transplant co-ordinator sat me down and told me in very sober terms that it might take a week to find a suitable donor. Or it might take years. What's more, the chances of finding a suitable match for Thando were reduced even further, because she had a rare blood group. It wasn't unknown for patients to literally die waiting and without a new liver Thando had less than a month to live.

Shadowy blur

By now the hands of the stopwatch were spinning so fast they were a shadowy blur. I went home that evening to rest, my mind a jumble of thoughts and most of them fearful. I'd just lain down when the co-ordinator called me to say the unimaginable. They'd found a donor!

The medical staff were astonished. I remember one of the senior surgeons saying to me: "Someone up there must love your wife." Another asked me in amazement: "How did you do it?" I hadn't done anything. All I'd done was to pray. But a man died that afternoon and his family kindly allowed his liver to be given to Thando. I'm very grateful for that. I signed the consent form that night in a small office adjacent to Thando's bed. My mother, who had put aside her intense dislike of flying to come over from Ghana, was by my side. It was August 18 2011.

It was a long operation – six hours or so – and I sat in the waiting room throughout the night. Around three in the morning one of the doctors came out to find me. He looked barely old enough to have a driver's licence, let alone assist in an operating theatre, and he said to me: "Your wife's liver is in and it's looking nice." And he was right, it was looking nice. When Thando woke up she was completely different and glowed with an inner radiance. She didn't quite know what had happened and asked the nurses whether she'd had a baby. She still had her quirky sense of humour.

Living with a transplanted organ is a delicate balancing act. On the one hand you take medicines to suppress your immune system in order to prevent rejection of the transplanted organ. But those same drugs leave you open to the risk of infection, which in turn requires more medication. I read all the material and went to the briefings on the do's and don'ts of caring for someone with a transplanted organ.

Thando came home at the end of September with a sackful of medicines and was really getting better. She'd wear her face mask and take walks regularly and became a little stronger every day. Then what we feared happened and in November she picked up an infection and had to go back to Donald Gordon. She never came home again.

Organ failure

Thando had a second liver transplant on December 13 2011 and this proved to be one transplant too far. In early January her organs began failing one after the other. It was like watching dominoes fall in slow motion. She was pronounced brain-dead on the morning my brother and his wife arrived from Singapore to be with us. By then all I was clinging to was hope. There was a mandatory 24-hour period before Thando's life support could be switched off, an expiry period of sorts allowing for a miracle.

The 24 hours came and went and when the doctor called me into her office, I was still hoping she was going to smile and say the dominoes had started to right themselves again. Instead she thrust a typewritten paper across the narrow table and burst out crying. It was ironic that in the same little office where weeks before I'd signed the consent form to give my wife a chance of life, I was about to sign another piece of paper to take what remained of her life away.

Ekow's mother, Sophia Duker.

We gathered silently around Thando's bedside: me, her parents, her brother and sister, my brother and his wife. And her aunts. It was dreadful knowing, but yet not quite knowing, what to expect. It was all over in less than two minutes. A nurse drew the curtains shut and began to unplug hoses and flick switches and turn dials to the "off" position. It was all rather workmanlike and reminded me of a plumber packing up his tools at the end of a busy day. Before long the gentle rise and fall of Thando's chest came to a stop and the cardiograph flatlined just like it does in movies. Except in this movie I wasn't going to go guns blazing after the bad guy, because the bad guy in my case was God.

Friends and well-wishers said to me: "You must accept what has happened. It's difficult, but you must accept." This was usually said with a gentle hand on my shoulder and an earnest look that brooked no dissent. I heard this refrain so many times I wouldn't have been surprised if they'd rehearsed it. I would nod and smile thinly but I'd be fuming inside. Why on earth should I accept? I slipped into banking executive mode and demanded answers … or else …

Amid the mourning I went home to Ghana to draw breath and a friend came – as friends do in Ghana – to my mother's house to offer her condolences. I sat there on the green damask sofa with the faded fractal patterns and waited for her to begin. She sat at the other end of the sofa, too far away to lay a hand on my shoulder but close enough for me to see the sincerity in her eyes.

'No explanation'

I expected her to spout a variant of the docile acceptance mantra I'd heard so many times before and in anticipation I arranged my features into the required look of understanding. But to my surprise she simply raised a finger in admonishment, looked at me and said: "God doesn't owe you any explanation. None whatsoever." I was taken aback at first because she wasn't supposed to say that. She was supposed to play nice. Yet somehow those curt words highlighted the distance between me and God and, slowly, I began to trust.

The curtain to that magical place, the same one I'd glimpsed through advanced mathematics and in the pages of good writing, had once again been pulled aside. I felt a deep peace that mutated into a curious joy and over time added a dogged dimension to my faith.

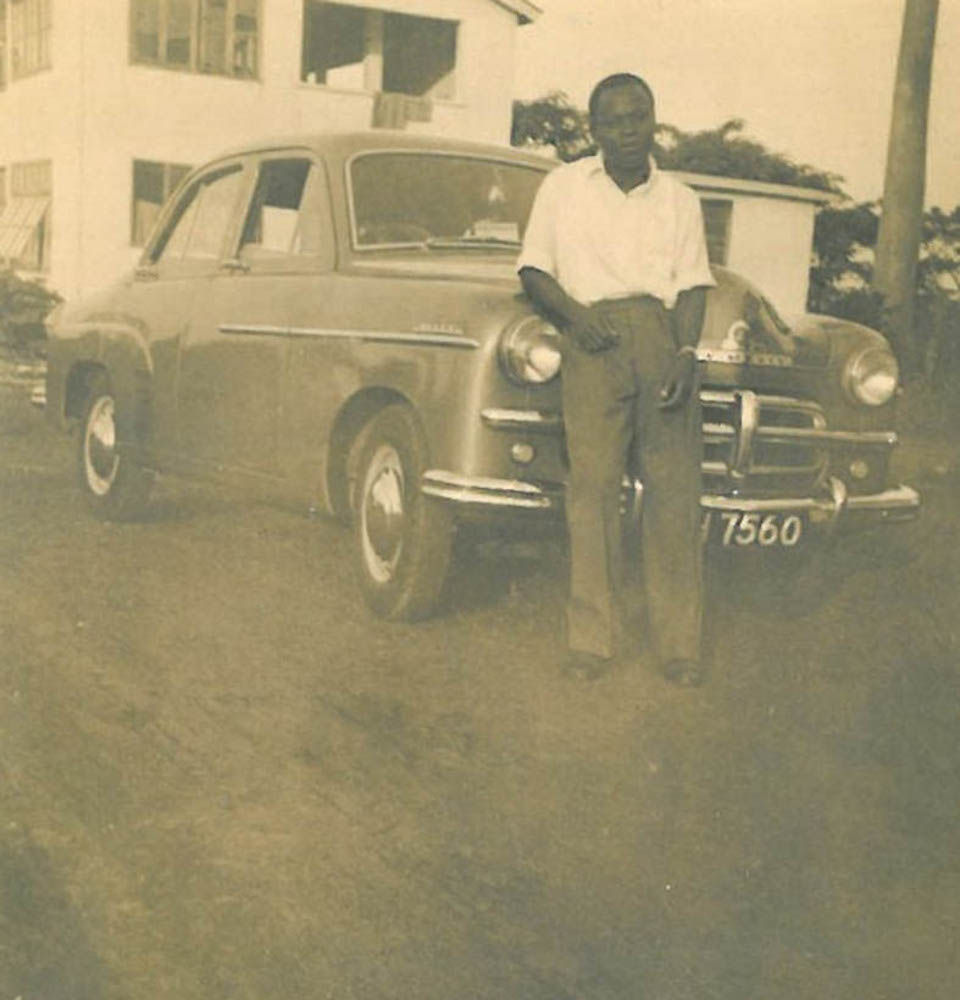

Ekow's grandfather, the Right Reverend Moses Debrah.

Ekow's grandfather, the Right Reverend Moses Debrah.

Now two years after Thando died I can look back and see an unbroken vista of love signposted by the oddest occurrences that I think point the way to someone out there looking out for me. With hindsight and despite my impatience, Thando was only transferred to the Donald Gordon when the donor was "ready" and not a day before. And then there was the time after her first organ transplant when I was short of R40–000 and a friend I saw only intermittently called me out of the blue to remind me of the money I'd entrusted to him almost two decades before in London. I admit it was very unbankerlike of me to have forgotten and it took a fair amount of prompting from him before I remembered. And the amount? R40–000.

I also remember how the day before they switched off the machines, you could have stuck a pitchfork in Thando and she would not have responded. Then our priest came along and very gently made the sign of the cross on her forehead and her whole body shook violently. It was as though she'd been shoulder-charged by a Springbok.

Gentle rain

I remember too the gentle showers of rain that fell at each of the three memorial services we held for Thando, in Johannesburg, Bulawayo and Accra. Not during the service but literally within seconds of the priest uttering the closing blessing. And then a silver-haired counsellor in Accra quietly explaining to me that Thando had simply gone over to a place where they communicated on a different frequency to us. (As an engineer, I got that.) And that frequency, she said, was love. Then there was the sandalwood.

As long as I can recall, I've had a fondness for its distinctive fragrance and its warm, rich and woody aroma. Some call it the divine essence but I didn't know that then. I do remember how, on my way back from Ghana, an intense smell of sandalwood enveloped me on the Gautrain, only to vanish as suddenly as it had arrived. Weird? Definitely.

I'm a different person to the one I was before Thando died. I'm not as afraid as I used to be. A friend once said to me that the command repeated most often in the Bible is not "be good". It's not even as Google famously said "don't be evil". It's actually "don't be afraid". Which of course is easier said than done.

What works for me is to live a life of gratitude; gratitude for each moment and the opportunities that come wrapped with it. Not because our time here is short and I have to cram as much into my life as I can before I die. That's just a foot race against a stopwatch that I'm bound to lose. And as I discovered with Thando, the stopwatch is rigged anyway. But being grateful, I find, takes the fear away like nothing else I know.

These days I divide my time unevenly between banking and writing. (I think they get the equity story; I do different presentations now). But every now and then the curtain ripples and I glimpse an otherworldly beauty on the other side. And it tells me that everything is going to be alright.

Ekow Duker is an oil field engineer turned banker. His debut novel Dying in New York will be published in August by Pan Macmillan.