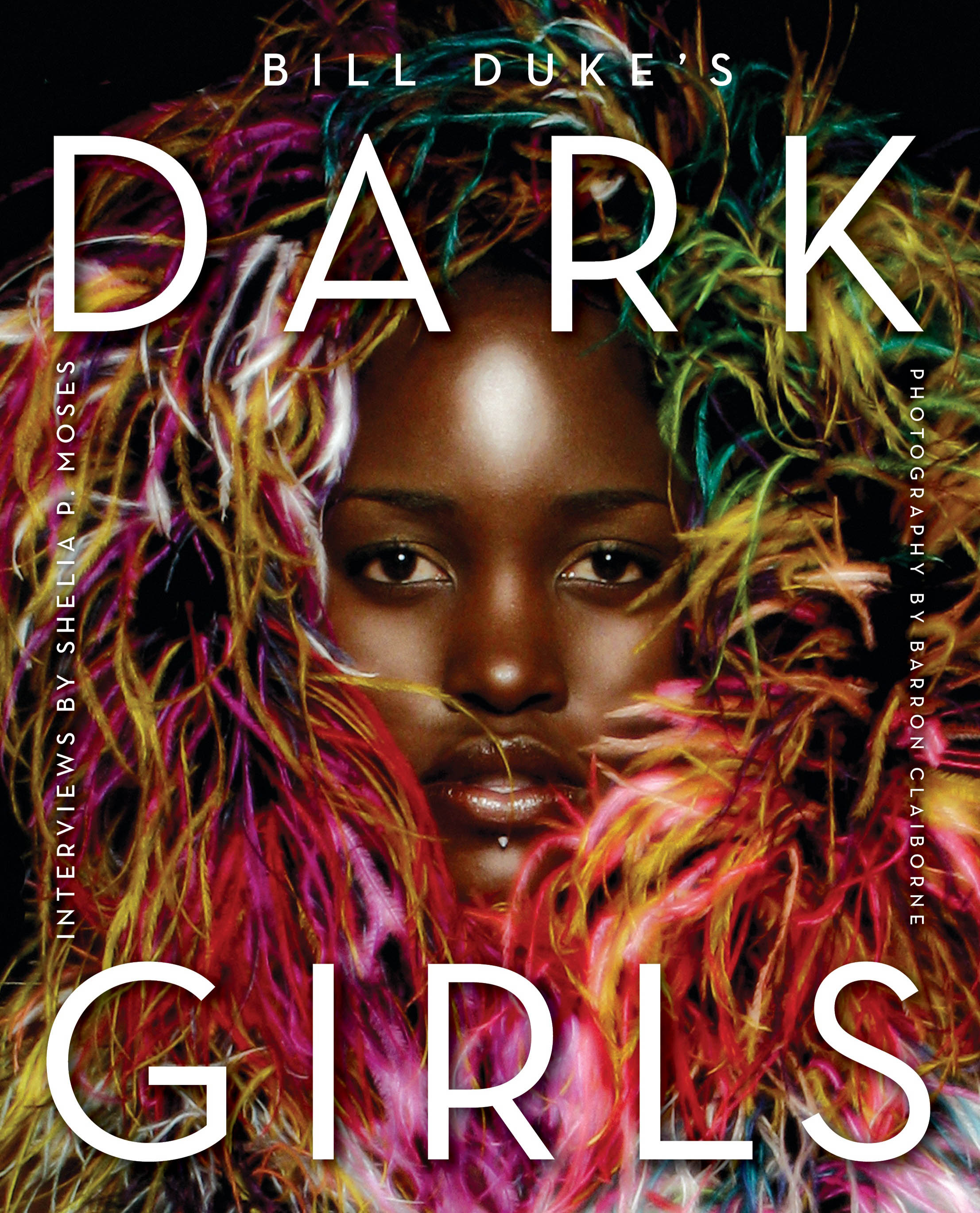

What started out as the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People award-nominated documentary on skin tone, by filmmakers Bill Duke and D Channsin Berry, is now a full-colour book celebrating dark-skinned women. ‘Dark Girls’ features beautiful photography and interviews with celebrities such as Lupita Nyong’o, Vanessa Williams, Steve Harvey’s daughters Brandi and Karli Harvey and Pauletta Washington, who reflect on what their dark skin means to them. This is an edited extract from Bill Duke’s introduction to the book.

I was excited like any first grader would be when I put on my new clothes for the first day of school. Clothes that I am sure my parents spent their last dime to buy for me. I was a normal, happy little boy. I did not know that it mattered that the teacher and most of the students were white.

“Stand up and shake each other’s hands,” the teacher instructed the students. Not one person touched my black hands. Not one! Then she asked us to stand and state our names. When it was my turn, I stood, but I could not speak. The fact that no one touched my dark hands had silenced me.

“What is your name?” she asked.

“Duke,” I managed to say.

“Duke. Is Duke your first name or your last name, young man?”

“No, it is Bill Duke.”

Laughter rang across the classroom. On the ceiling. On the walls. My darkness was not welcomed. I sat back down, and my normal little world changed. It has never really been the same since then. When you realise others will harm you just because you are not their skin colour, life starts to look different. When my teacher gathered us for lunch, I sat alone. The little white boys were ready to finish the job they had started in the classroom.

“‘What’s your name?’” one boy asked another boy, as if I were invisible.

“My name is Duke,” his friend said.

“Is that your first name or your last name?”

“‘That’s my last name,’” the boy answered as they all laughed.

“Oh, I thought it was n–,” another boy laughed.

“No. My name is black n–,” one boy said.

‘I wanted to wash my darkness away’

I don’t remember anything else after that. When I was aware of my surroundings again, I was running into the house past my parents. I went into the bathroom, removed all of my new clothes, threw them on the floor, and ran bath water. I wanted to wash the pain away. I wanted to wash my darkness away. The proud little black boy I used to be was gone. After my bath I was still “black n–” like the white boys called me. I remembered how my mother used bleach to make towels and other linens white, so I thought it would turn me white, too. As I put the jug to my lips my mother stopped me.

“They called me a n–, Mama,” I whined.

As she removed the bleach that would have killed me from near my lips, she began to cry. She knew. She knew my blackness was not welcomed. My little sister ran in and started crying, too. My father did not cry. His face was like stone. He knew that my struggle as a black man had begun. He knew that I was about to walk down the same road he had travelled. He knew I was no longer just his son; I was a n– to my white friends. He was hurt to the core of his soul.

That was the day my parents became even more protective of me and my sister. I went back to school the next day holding my sister’s hand, trying to protect her from what would become a lifetime of pain for both of us. My dad went off to work angry, and my mom tucked her heart back into her body and went off to the Dutchess County mental ward, where she worked for 30 years. She worked with the brokenhearted and the unwanted. She knew pain, like her patients’ pain, had come home to her children.

My momma and daddy continued to give us all the love they had. They tried so hard to show us a better world. There were times when they had little to no money to do things for us, not even enough money to go to the movies theatre. On Saturday nights we would walk to the local theatre and sit down on the pavement. That was where my life as a filmmaker really began.

“What do you think that man does for a living?” my father would ask, as a man walked past us. With Yvonne’s help, I would just make up a story about the person to tell our parents. “What about him?” my mother would ask.

We would do this for hours. Just the four of us, as a family. We had no money to go inside – besides, our darkness was not welcomed. For years to come we remained close and protected each other with love. My mother and father are gone now, and I have my dark girl sister left to love and to be loved by. I have her daughter Nalo, who is also a dark girl.

Telling the story

This book is for my mother, but it is also for Yvonne and Nalo and all the dark girls around the world. My mother inspired me to direct the documentary Dark Girls. The talks I had with Yvonne and Nalo about their journey as dark girls also inspired me. Watching them be ignored by men because of their darkness made me determined to tell their story one day. When I started the research, I did not have to go to the library or a bookstore. I had lived my life with dark girls.

When I started recording their stories for the documentary, my mother’s face was etched in stone with every word they spoke. I could hear her voice saying: “Tell the story, child. Tell the story.” When the documentary was aired on OWN, women from across the country reached out to me to say: “Thank you for telling our story.” Like many people in the industry, Shelia P Moses called me after the documentary and said: “You know, that should be a book.”

The selection process for the women included in Dark Girls was tough. Many women were interested. We used the historical standard of the brown paper bag. The women in this book are darker than that bag and unfortunately our society still gives preference to those who are lighter. Some of the beautiful women featured here are very dark, and others are just the darkest in their own families.

Dark Girls honours the women society would like to ignore, the ones darker than the paper bag. The impact that I hope this book will have is twofold. First, I hope that the pictures and words will enable young dark-skinned girls globally to see and accept their own beauty and begin to dissolve issues of low self-esteem. Second, I hope to influence the global ideology that perceives whiteness as more beautiful, acceptable, and more meaningful than darkness.

My prayer for Dark Girls is to help readers to rethink the impact this debilitating and destructive idea has on our children in the present and will have on our children in the future. To my dark girls, you are loved. I honour you – and yes, your gorgeous darkness is welcomed on this Earth.

Dark Girls is published by Amistad, an imprint of HarperCollins publishers, and will be released in South Africa on December 15