Mndazi Betty Maluleka sometimes shows a flicker of recognition for her daughter

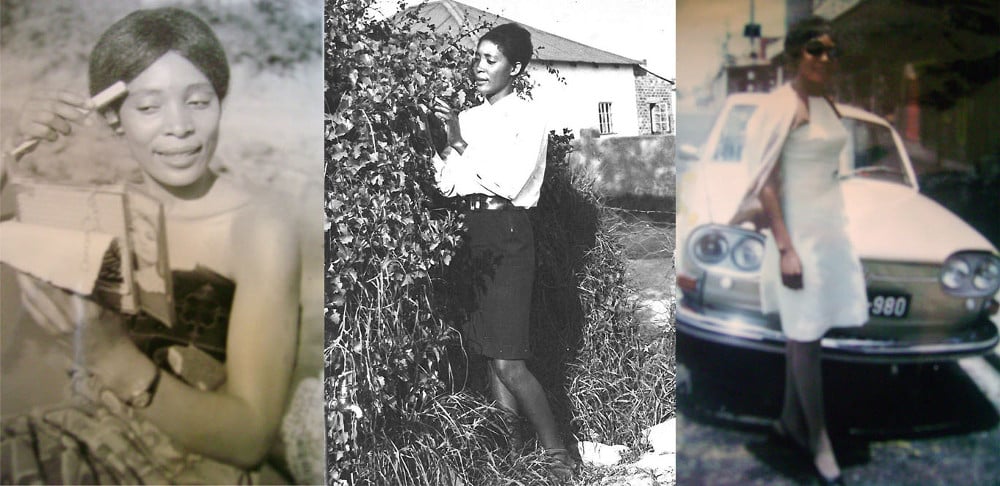

Mndazi Betty Maluleka

I watched my photographs curl and go black at the edges. They were writhing as if they could feel my agony. I still remember how the small red flames hissed with malevolent glee as they crept through the picture book, devouring my photos until there was nothing left except my sister Hilda’s voice crowing in my ear.

“What are you doing with a white man? And he’s a photographer, for God’s sake!” She said this as if photography was the worst possible profession for a man, black or white.

My brother Joseph added gently: “It’s for your own good. You can’t live in a fantasy world.”

I must have mumbled my disagreement because Hilda chimed in immediately. “Black people are meant to do as they are told!” she cried and Joseph laid a conciliatory hand on my shoulder. I felt him nodding, willing me to nod as well.

I wondered what I would tell Carlo. That I wasn’t ever going to pose in front of the Eiffel Tower while his camera shutter clicked and chattered like a Xhosa woman. It was the 1960s after all and my dream of becoming an international model was as illogical as the idea that one day we’d have a black president.

I was born on July 4 1944. My first recollection is of a small house in Louis Trichardt. The guide books describe Louis Trichardt as “a picturesque town at the foot of the Soutpansberg mountain range in the Limpopo province of South Africa”. I can’t imagine they’re describing the same town I grew up in. We worked for a white farmer who grew bananas and mangos on his land. It wasn’t picturesque; it was hard.

I barely remember my father. He was called up to fight in World War II and never returned from North Africa. I’d ask my mother where he’d gone but she’d shake her head and say my Shangaan name, Mndazi, and frown.

Ntombenhle Bridget Radebe

I also hardly knew my father. All my mother told me was that he was a credit clerk for CNA, the stationery chain. But that was just a cover. My father’s real job was to ferry sensitive messages for one of the banned organisations. I imagine him having whispered conversations in darkened rooms and peering out of a half-opened door before stepping into the street and hurrying away.

My mother’s family didn’t like my father. They said he was trouble.His family didn’t think much of my mother either – she was Shangaan.

Mndazi Betty Maluleka

Ntombenhle is my daughter’s name but I call her Enhle. It means beautiful girl. Enhle used to laugh and say I’d been given a very “in-your-face” Catholic upbringing. I had my mother to thank for that. I went to a Catholic boarding school in Louis Trichardt and would recite the antiphons without thinking that there was perhaps an irony in the words: “The rich suffer want and go hungry, but those who seek the Lord lack no blessing.”

I fell in love with the drama productions at school. It didn’t hurt that I was slim and tall with angular features that later Carlo would call impresionante (impressive). I liked that. It sounded imperial.

But the farmer evicted us after my cousin and I left a candle unattended and almost burned down the house. We moved to Brits and then to Atteridgeville where the three youngest children – Emily, Girlie and I – lived on our own. By then our mother had died of breast cancer. The nuns discovered us living all by ourselves and, in a fit of righteous horror, decided to split us up. I was 13 at the time.

A young Mndazi Betty Maluleka poses for the camera. (Photos: Supplied)

I was sent to Saint Anne’s boarding school in Alexandra and that’s where I met Carlo. Yes, it was a Catholic school but I’d often sneak out with my friends to go dancing. As I picked my way through the sweaty bodies gyrating in the semi-darkness, I’d hear my mother scold me: “Mndazi! What are you doing in this place?”

Carlo was Spanish, a photographer who lived in the United States. I’d gone to visit my brother Joseph when he sauntered up to me one evening with a leather-clad camera swinging jauntily from his neck. My friends scampered and hid behind me, tittering as he spoke to me in curiously accented English. He wanted to take pictures of me because I was … impresionante. But Hilda put a stop to that. In her mind, and her mind was immovable once it was set, Carlo’s photographs would bring me nothing but misery.

The nuns offered me a scholarship to study nursing at a hospital close to Atteridgeville. I accepted it reluctantly because in my heart I wanted to go away with Carlo. I think he went back to the US soon thereafter; I never saw him again.

Ntombenhle Bridget Radebe

My father really enjoyed the fact that my mother was so stylish. She could turn men’s heads towards her in a crisp or languid arc, depending on how fast she was walking. She was fashionable, warm and animated and could start a conversation with anyone.

My father showed my mother off at every opportunity and bragged about everything from her cooking to her crochet work and her dexterity at the waltz. I often wonder what she saw in him. She could have had anyone but he went one better and actually had everyone.

They named my brother Mlungisi Theophylus Radebe; he was born on September 8 1974, five years before I was. Mlungisi’s birthdays always came with so much cake and food it was a wonder he remained so tall and skinny.

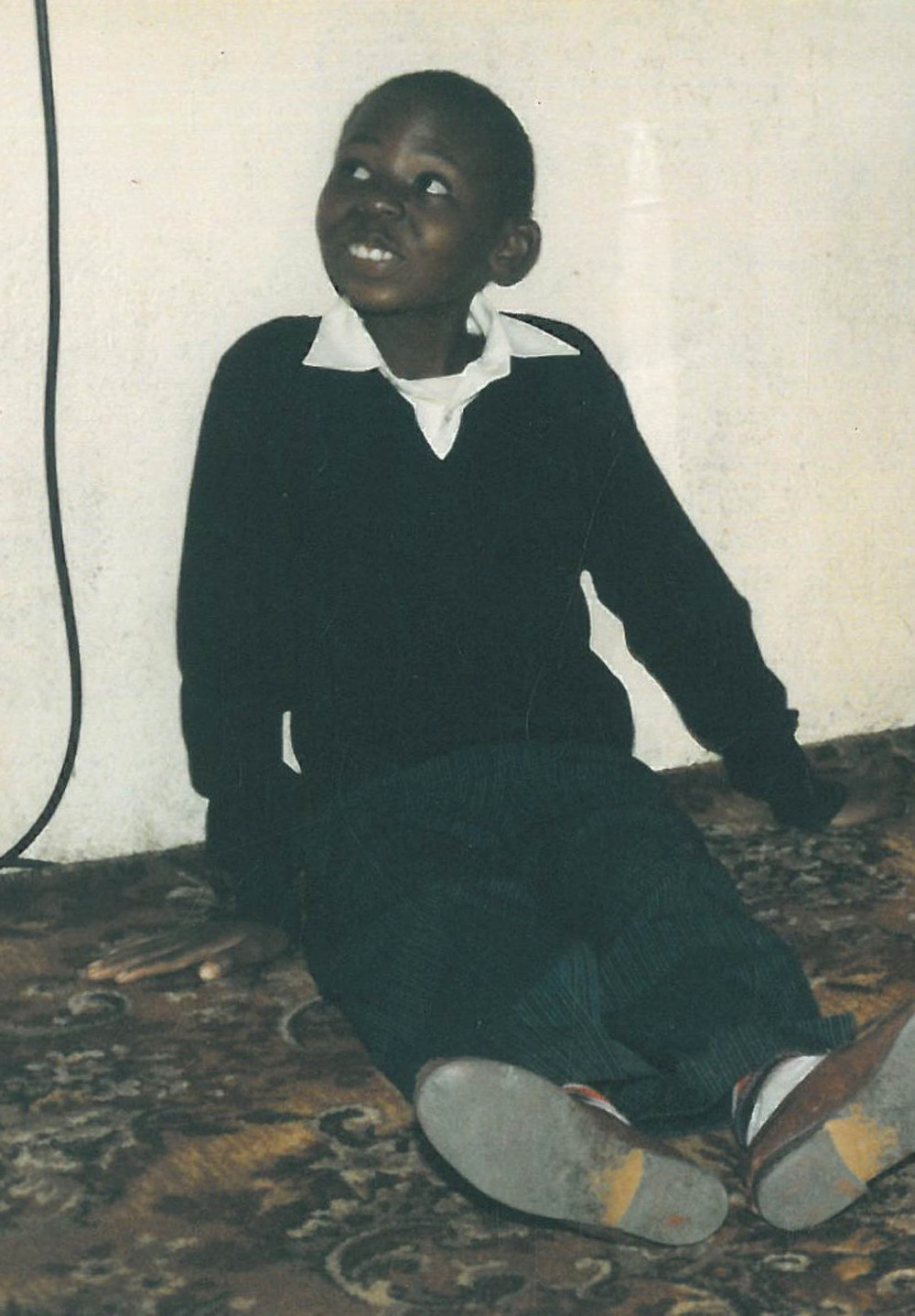

Betty Maluleka’s son, Mlungisi Theophylus Radebe.

The trouble my aunts had foreseen came in the form of the security police who raided our house in Meadowlands, Soweto, with savage regularity. They didn’t believe my mother when she protested and said she didn’t know where my father was.

She was never one to be cowed and one night she spoke back to one of the police officers. He hit her and, of course, my brother Mlungisi ran across to help. They hit him too and they must have dislodged something in his brain for he was never the same afterwards. He was only nine years old.

Mndazi Betty Maluleka

They found Alex’s body in an abandoned mine shaft and that was the cue for his family to give full rein to their venom. They accused me of leading his attackers to him, as if I would ever do such a thing to Alex. They did all they could to evict us from the house he had left to me and even made me change my name back to Maluleka.

I drew the line when they said Mlungisi and Enhle should change their surnames too. One night they even tried to burn us in our beds, something the security police, for all their brutality, had never done.

It was difficult bringing up two sickly children on my own. Mlungisi’s epileptic fits seemed to trigger Enhle’s asthma attacks and sometimes I wouldn’t know which child to attend to first. In the end it didn’t make sense to stay in Meadowlands any longer. There was too much hate and too much hurt, swirling around everywhere I looked.

So we moved to Pimville, which was a much more comfortable neighbourhood. I’d put Mlungisi in Avril Elizabeth, a school for the mentally handicapped in Germiston and Enhle had started at McCauley House Convent. I could scarcely afford their education but I was determined to do the best for my children; I put in all the overtime I could.

Ntombenhle Bridget Radebe

I remember petrol and fire and screams that pierced the darkness, but most of all I remember the taunts of the other children in Meadowlands.

They called us snobs because my mother made us speak English all the time. I was so relieved when I got into McCauley House. At least the nuns didn’t cane the girls the way they did in the township.

Bridget Radebe.

I found it really strange at McCauley House. The white kids kept to themselves and the handful of black kids in the school didn’t talk to me either. I suppose in the girls’ desire to conform, none of them wanted to be tainted by association.

Mndazi Betty Maluleka

I was having difficulty remembering things. Small things, like the names of people I’d known all my life. I’d stare blankly at them, their names a million miles from the tip of my tongue.

That’s when I started taking memory pills and I got Enhle to take them too. I told her they’d help her to pass matric. Enhle was smart and energetic and flung herself into everything she did, like she only had hours to live. Soon she was the one reminding me to take my tablets. As for Mlungisi, he carried on in a world of his own. Not long after Alex was killed and while we were still in Meadowlands, Mlungisi went missing for three whole days.

I was beside myself with worry and walked the streets for hours trying to find him. Since then I’d hardly let him out of my sight but I still had this lurking fear that he’d go wandering off one day and never come back.

Ntombenhle Bridget Radebe

I made it into the University of the Witwatersrand to study accounting. In my excitement I didn’t think much of the fact that my mother was becoming increasingly forgetful. She’d go to the mall with a shopping list and return with only half the items. When I’d ask her about it she’d shrug and say she forgot.

Or she’d become aggressive and shout at me until I cried. I was dating now and was spending less time at home anyway. Then one day my mother told me she felt like I’d abandoned her. That made me cry all over again.

I was in my second year at Wits when Mlungisi went missing again. My mother phoned me and I remember her voice was tight with worry. I left campus at once and together we scoured the streets around Pimville without success. Two months passed and we still hadn’t found Mlungisi. It was the most obscure coincidence that brought Mlungisi back to us.

A neighbour had guests visiting from Witbank and one of them noticed a familiar face in a photo of the neighbour’s children, posing with a friend of theirs. That friend was Mlungisi. No one knows how he managed to travel the 150km to Witbank but he was working in a coalyard over there, shovelling coal into a donkey cart that plied the streets. My mother went to fetch him right away and we were overjoyed to have my brother back home again. Our prayers had been answered in the most dramatic way.

Mndazi Betty Maluleka

By now I was forgetting things in the theatre. Not often mind you, but enough for the other sisters to ask me what was wrong. A surgeon would ask me for a scalpel and I’d have no idea what he was talking about. He might as well have been speaking Chinese. Or Spanish.

Mndazi Betty Maluleka was a brilliant nurse, according to the hospital’s neurosurgeon, who later diagnosed her dementia.

Ntombenhle Bridget Radebe

Less than a year after Mlungisi came home from Witbank, he went missing again. And despite my mother’s relentless searching, we have never found him. My mother’s forgetfulness became much more pronounced after Mlungisi went missing and her bouts of aggression got much worse too. She’d often become belligerent and would bunch up her fist and punch me when she didn’t get her way.

I learned much later that certain doctors had refused to work with her but I still wasn’t joining the dots. In June 2005, the matron from the hospital in the northern suburbs where my mother was working called me (I was an article clerk) and told me to come and fetch my mother.

I drove to the hospital to find my mother in the matron’s office; she was incredibly furious and resentful. The matron took me aside and showed me the papers my mother had signed in April, placing her on early retirement. My mother hadn’t told me anything. She’d kept on going to work and for a few months they let her come in. They were careful only to give her inconsequential tasks until they couldn’t handle it any more.

I took her home but she’d wake up at the crack of dawn and start to get dressed, insisting she had to go to work. She kept saying the hospital owed her money and that she had to get it back. She’d go shopping and forget where she’d parked her car and would go to the police station and report the car as stolen.

Then of course the cops would find her car parked in the basement of a shopping mall and scold her, kindly at first, then with increasing annoyance. This happened several times. My mother would wander the streets of Johannesburg, leaving me to guide her over the phone as though we were playing a game of Blind Man’s Buff.

What do you see in front of you?

Walk to the end of the road.

Read out the name of the cross street.

Wait for me. Don’t move (But of course she did).

Mndazi Betty Maluleka

They owe me money. That’s all I have to say.

Ntombenhle Bridget Radebe

In 2006 I went on an exchange programme to Canada as part of my audit training. I’d call my mother from Toronto and she’d tell me that some women were helping her to get her money back from the hospital. I knew the women she mentioned but didn’t pay much attention to it. I came back after six months to find my mother in the most terrible debt.

Her account was overdrawn by a staggering amount and her transaction record showed large withdrawals of up to R10 000 at a time. She’d also been buying far more petrol than her Toyota Corolla could possibly consume and she’d replaced the tyres so often you’d think she was a Formula 1 driver.

She’d also taken out a credit card, something she’d never done before, and had spent all the credit she’d been granted. What’s more, she’d cashed in all her policies and was on the verge of being evicted from the house because she’d stopped paying her bond. Now almost a decade later, some of those women who supposedly helped my mother while I was away still can’t look me in the eye.

I worked hard to get my mother’s finances in order and negotiated payment arrangements with the banks. Amid all this I was trying to study for my board exam. I put on a lot of weight because my mother would forget she’d given me food a few minutes before. It was easier to eat than to argue.

There were many good days though and when they came along my mother and I would sit and chat like nothing untoward had happened in our lives. But I was worn out and when a girlfriend in London asked me to come over for a two-week holiday, it was all I could do not to run to the airport and barge through the first boarding gate I saw.

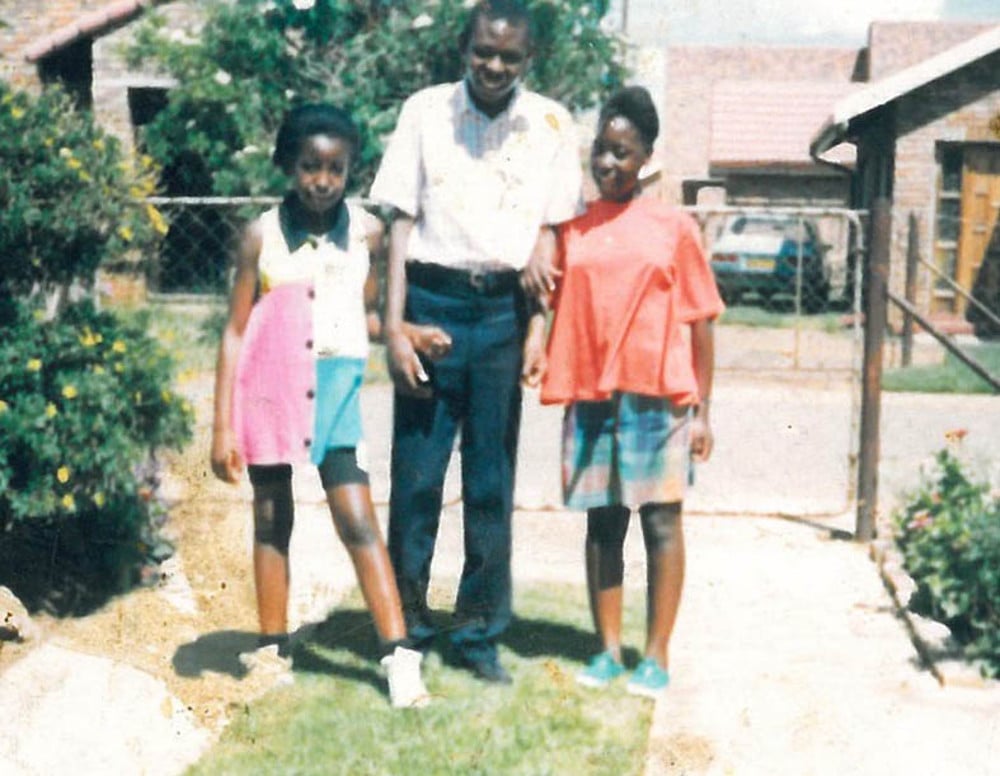

The family never found Mlungisi (centre).

My aunt Girlie came to stay with my mother while I was away but my mother would lock Girlie in the house and go looking for her money. She’d get lost and the police would find her wandering alone on the streets and bring her back home. Eventually they tired of picking my mother up and one day they drove her to a hospital not far from her home in Pimville and had her committed. I returned from London to find my mother in a ward for the mentally ill.

She was surrounded by baying lunatics and I wept when I saw her lying on her bed. She’d been drugged to the point of near-paralysis and could barely turn her head to look at me. I pleaded to see a doctor but didn’t get to see one for two weeks. The other patients would beat my mother and take her clothes, her food and the underwear I bought for her. By the time a doctor came to see me, my mother was skeletal.

The doctor, a woman in a white coat, told me my mother had dementia and that she wasn’t going to get any better. To my surprise, she refused to release my mother into my care, saying she had strict instructions not to do so. I was bewildered.

I asked for an explanation and was told I’d abandoned my mother and was either unable or unwilling to look after her. I was terribly ashamed to hear the doctor say that. She then handed me a list of nursing homes and urged me to visit them to see whether I could find one that was suitable for my mother. When I objected, the doctor threatened to have me committed. In the end she relented a little and suggested I see a psychologist at the hospital – for my own sanity.

Defeated, I went home and began going through my mother’s papers, not quite sure what I was looking for. I came across an old invoice for R2 000 from a neurosurgeon at the hospital in the northern suburbs where my mother had worked.

I went to see her and she told me my mother had been one of the most brilliant nurses at the hospital. She’d run tests on my mother when she’d started behaving erratically and confirmed she was suffering from dementia. It was just as the other doctor had said.

The neurosurgeon very kindly wrote me a note asking for my mother to be released into her care. That letter was like the key to an impenetrable castle. I was able to take my mother home with me to Woodmead that very day. I refused to send my mother to a nursing home and insisted she stay with me. She’d been in the ward for the mentally ill for almost four weeks.

Mndazi Betty Maluleka

Ntombenhle, my daughter.

Ntombenhle Bridget Radebe

My mother returned to her house in Pimville a year ago. She stays with Grace, a live-in caregiver who loves her unreservedly. Being in familiar surroundings seems to help and my mother is much calmer now.

I know that one day the part of her that still flickers with some vestigial knowledge of me will go dark and she won’t recognise me any longer.

Sometimes I feel like it’s gone dark already.

Mndazi Betty Maluleka

Wait for me Mlungisi. Don’t move.

Ekow Duker is an oil field engineer turned banker. His novels, Dying in New York and White Wahala (Picador Africa) were published in August. He is Bridget Radebe’s life partner.