For the past two years – towards the end of February and just into March – two rather different creative creatures, say an appearance-conscious armadillo and an up-market eland, have a friendly face-off in the same arena.

Neither needs anything from the other. They can be regarded as different sides of the same coin. And being in close proximity there’s a mutual rub-off in the friendly but serious battle of the art brands.

We’re talking Cape Town’s annual Art Fair and the Guild International Design Fair at the V&A Waterfront.

And so it was that on the opening night the crème de la crème of ultra-cool Cape Town set out to be seen shimmying up to each other and “pointing teeth”, well, until something more appealing came along. Dress code was sometimes in direct competition with designs and in some cases just as nonfunctional.

The Guild fair took place at its usual spot, at the beautifully appointed Lookout.

This year the Art Fair swopped the rather busy storeyed feel of the BMW pavilion for a highly successful campus sprawl, which stretched from the Avenue to the Bascule Bridge designed by Italian architect Laura Vincenti of Artissima. This was an approach taken by the early Basel art fairs.

Many promises are made in the hype that precedes these events. And to be fair, much of it was fulfilled. Visitors want to be seduced but not taken for a chump, although it can sometimes be a tenuous tightrope trip between the two.

A first event always carries some of the charm of the new but as these fairs are now well established, visitors have grown more critical and conscious of the emperor’s clothes syndrome.

The fairs have grown since last year: the Guild from six stands to 12, with four new collaborations, and the Art Fair to 45 gallery stands including the Kenyan Circle art gallery, the Italian Galleria Continua and Zimbabwe’s First Floor Gallery.

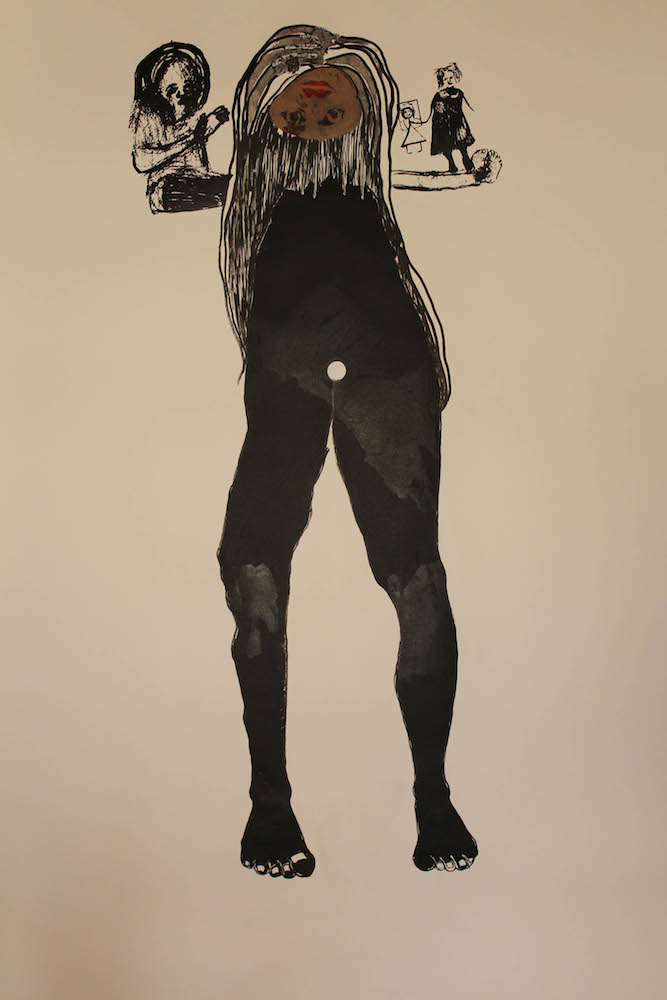

Raising Your Own by Virginia Chihota.

The purpose of both fairs is to draw the attention of collectors and galleries. The fairs aim to be of an international standard and to create platforms to exhibit top art and design works by contemporary South Africans, pan-African contributors and internationals. They are a place where museum directors, gallerists and patrons can meet.

You would have found familiar designers and artists and a number of newcomers. The Guild introduced the Massoud siblings and Dutch artist Frederik Molenschot, and Art Fair brought in London’s Tiwani Contemporary Gallery.

In keeping with a global trend, the Guild provided designs with an emphasis on high-end craft and interesting uses of material. The overall feel was lots of highly finished and glossy metal work, for example, Thomas Heatherwick’s extruded aluminium bench and Kendell Geers’s subversive patinaed bronze paraffin tin, titled Stool.

In strong contrast, there were the distressed metal surfaces of the pan-African artists of DNA, who were at last year’s fair, and Studio Swine’s curiously organic, pumice-like cabinets of aluminium foam. You would have seen irregularly shaped glasswork and its metallic equivalent, crafted wood, both worn and with a hard-edged cut finish.

Clinging to the security of architect Louis Sullivan’s take on the law of all things organic and inorganic that “form ever follows function” (a guiding principle in architecture and design of the 20th century) wouldn’t have served you in relating to the Guild’s design exhibits.

And you can forget the words or notions of furniture and comfort in the same sentence. After all, whenever was status comfortable? Nevertheless, I imagine it would be hard to leave your tush parked for any length of time on the sheer edges and ridges of the black Star Wars bench or lie on a chaise longue whose surface was seeded with little glass beads. Both made the black granite egg appear more appealing.

The Guild’s designs are closer to current trends that celebrate functional objects you can’t use. This is pretty clear in the work of Molenschot together with Gone Rural Swaziland’s spill of nonutilitarian woven indigo innards. We were drawn to them precisely for their nonfunctionality as we were to the “what were you smoking” Haas Brothers who teamed up with Monkeybiz to create beaded creatures with names like Fartin Odeur and Tail-Or-Swift under the title Afreaks and so “subvert the concept of hierarchy”.

It came as something of a reprieve to see Design Network Africa’s Cheick Diallo’s little wooden cabinet overlaid with leather squares and two small “ears” atop it or the rough-hewn humorous Tintin and Bijou characters of Bongolombas, which form part of the Artisan collection.

But I found the idea of walking over the image of a naked, exposed female figure in carpet form distasteful and detracting from the overall polish and standard of the Guild.

One of the primary joys of this year’s Art Fair was its layout. Its spacious flow made negotiating the numerous gallery stands and digesting their vast contents more possible. Eclecticism reigns in myriad forms and it’s difficult to gather threads to predict trends.

As has become the requisite of international fairs, both fairs included a variety of diversions such as tours, talks, performances, works in process, panels, performances and award ceremonies.

Each gallery stand had a different approach to curation. Everard Read’s Emma Vandermerwe explained that the gallery’s stand included, among other work, three solo exhibitions featuring Dylan Lewis’s land art, Nigel Mullins’s impasto-on-steroids paintings and a “conversational” exhibition between the photographs of Billy Monk and Daniel Morolong.

After the overload of visual stimulation, it was useful to return to a simpler palette: the quieter but no less dramatic black-and-white prints of, say, the David Krut Project or the tonal photograph of Mikhael Subotzky titled Cradle or Blank Projects’s Mário Macilau’s photograph Untitled from his series Outside Town.

In the end, my benchmarks for fairs of this nature are the artworks that remain with one long after the fairs are dismantled.

They are the ones that count.