When the news was announced in March that Kenya would be hosting a national pavilion at the Venice Biennale for the third time in the country’s history, what might have seemed an honour quickly became mired in controversy.

READ SA trips as Joburg lands on the steps of the Venice Biennale

Of the seven artists chosen to represent the East African nation, five were Chinese, one was a Kenyan-born artist living in Switzerland and the other was an Italian sculptor and hotelier who has lived in Kenya for 47 years. Artists and critics took to social media to decry what one commentator called a pavilion “fronted by a band of cynics”.

At a press conference at Nairobi’s National Theatre on April 14, Hassan Wario Arero, cabinet secretary in the ministry of sports, culture and the arts, read out a statement in which he accused the organisers of “wrongfully presenting themselves as the Kenyan pavilion” and “strongly condemn[ed] their acts of impersonation”.

Arero said the government would ask the biennale organisers to remove the Kenyan name and flag from the pavilion.

The biennale’s head of press and media relations, Cristiana Costanzo, said that countries appearing in Venice could only “officially request participation through a government or diplomatic authority”, deepening confusion in Kenya over who signed off on the pavilion.

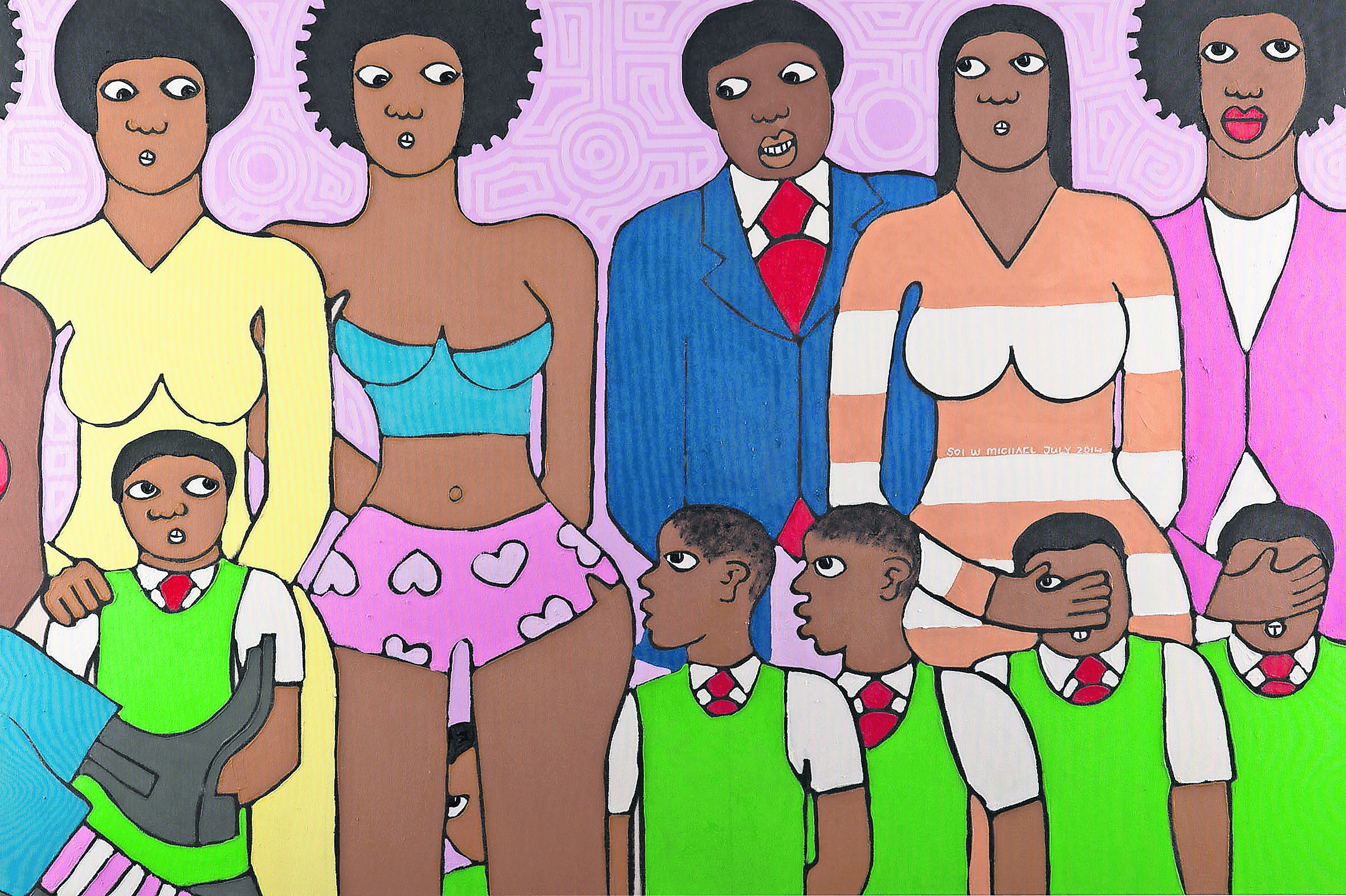

Artwork by Michael Soi

‘Frightening manifestation of neocolonialism’

Despite the uncertainty, much of the controversy has swirled around Armando Tanzini, a Livorno-born sculptor and resort owner who is the only artist to have represented Kenya in all three biennales.

But Tanzini, who is known for his carved driftwood sculptures and who says on his Facebook page that he loves Africa “because it’s innocent and poor”, is widely believed to be the driving force behind this year’s pavilion, which is being curated by another Italian, Sandro Orlandi Stagl.

For many in the tightly knit art world of Nairobi, the controversy has left a queasy feeling of déjà vu: in 2003, Tanzini spearheaded the inaugural national pavilion for his adopted country, in which, according to the words of one critic, he “placed himself and his Africanised works at the centre of the exhibition … while [the internationally acclaimed artist] Richard Onyango has literally been pushed into a corner”.

Two years ago, the Italian again appeared as part of a pavilion that was dominated by Chinese artists and roundly panned by commentators, who called it “a frightening manifestation of neocolonialism vulgarly presented as multiculturalism” and “primitivism at its very worst”.

Speaking recently by phone from his White Elephant Sea & Art Lodge in Malindi, Tanzini said he was saddened and surprised by the controversy, suggesting there was “a little bit of racism” behind the accusations of wrongdoing. He said Kenya wouldn’t have a presence in Venice were it not for his efforts.

“I am somebody that pushed the possibility [for the government] to understand what is the biennale of Venice,” he said. “If nobody selects anybody … we lose the opportunity to recognise the best artists in this country.”

‘Creation of an identity’

In an email, Stagl defended the choice of him as curator, citing the theme of this year’s biennale, All the World’s Futures, as the inspiration for a pavilion that focuses on “the creation of an identity”.

He cited precedents in which countries had often gone beyond their borders to invite artists whose work might comment on larger themes, such as nationalism or globalism. In 2013, for example, France and Germany swapped exhibitions for their respective pavilions to commemorate the 50th anniversary of a treaty on Franco-German friendship, and Germany invited four foreign artists – China’s Ai Weiwei, French-Iranian Romuald Karmakar, South African Santu Mofokeng and India’s Dayanita Singh – to represent it.

The inclusion of an almost entirely foreign roster of artists, said Stagl, would act as “a stimulus for other artists in Kenya to open up to a truly international dimension of art”.

In Kenya, though, a growing number of artists are finding international acclaim. East African art dealer Ed Cross described the pavilion as “a missed opportunity” to bring the likes of Wangechi Mutu and Magdalene Odundo, among the globally renowned Kenyans who predominantly live and work overseas, into conversation with their counterparts in Nairobi, where the art world has seen a fundamental shift in recent years.

“There’s a very exciting, vibrant art scene, and we’re getting a lot of international interest,” said Danda Jaroljmek, of Nairobi’s Circle Art Agency, which in 2013 organised the first local auction of regional art. “In [the African art world] East Africa was least known internationally, and that’s slowly changing.”

Circle Art Agency

Artist Michael Soi, whose satiric series Shame in Venice recently tackled the biennale controversy, echoed that sentiment. “I think it’s time to have a proper Kenyan pavilion … so that people can begin to see the quality of work that comes from Kenya.”

Demand for contemporary African art

His politically charged works, tackling issues such as bad governance and corruption, reflect a dynamic Kenyan voice that will be absent from this year’s biennale.

The controversy over the Kenyan pavilion comes at a time of unprecedented demand for contemporary African art, with London auction house Bonhams regularly setting new records for African works, and a growing platform for the continent’s artists provided by international showcases such as 1:54, Europe’s leading art fair dedicated to contemporary African art, and dOCUMENTA, the contemporary art exhibition held every five years in Kassel, Germany.

In Venice, Angola’s national pavilion won the prestigious Golden Lion in 2013. The selection of Nigerian-born Okwui Enwezor to curate this year’s biennale raised hopes for more inclusiveness and awareness of African art in Venice, where 36 artists of African descent will be featured in the central pavilion, including Mutu.

That international exposure, however, hasn’t translated into direct action on the part of governments, whose efforts are necessary if African nations want to take part in what’s been dubbed the “art Olympics”, according to Raphael Chikukwa, the director of the National Gallery in Harare.

Chikukwa said by email that it was “impossible for us here in Africa” to organise a Venice pavilion without robust government support.

‘Not exactly saintly’

This year Zimbabwe will host a national pavilion for the third consecutive biennale, which Chikukwa estimated at a cost of about R4.5-million – an amount largely donated by the country’s ministry of sport, arts and culture, which, after two successful runs in Venice, has included the operating costs for the biennale in the National Gallery’s annual budget.

That astronomical cost has fuelled speculation in Nairobi over why artists from China – a wealthy nation – are appearing in Venice under the Kenyan flag. Cross said the internal mechanisms of the biennale were “not exactly saintly” with regard to sponsorship of pavilions.

Still, the underlying sentiment in Kenya is that the government needs to take a more proactive role in allowing local artists to represent their nation. Chikukwa said: “We in the arts [in Africa] must educate our politicians to see the need to invest in the arts and these platforms.”

If there’s a silver lining to the current dust-up in Kenya, it’s that the public outcry has galvanised the local arts community and spurred the government into action.

Sylvia Gichia

“The response from local artists, gallerists and stakeholders has been encouraging,” said Sylvia Gichia, the director of Nairobi’s Kuona Trust, an artists’ collective and residency.

The involvement of the ministry of culture, she said, wouldn’t have materialised without public pressure, and the government was already putting its muscle behind efforts to organise a more inclusive and representative national pavilion for Kenya at the 2017 biennale.

“The artists have to hold [the government] accountable,” she said, while expressing hope that the controversy of the past two biennales wouldn’t be repeated again.

Whether the government’s words will translate into action remains to be seen. Soi, for one, remained sceptical. “For the longest time, art in Kenya … has not been something the government would take seriously. I don’t believe it’s going to start now.”

He laughed, and added: “They may actually prove me wrong.”