Mauritius is often described as a tax haven because it levies little to no tax.

Globally, initiatives are afoot to close tax loopholes and South Africa is one of the frontrunners – its new treaty with Mauritius removes the allure for tax-shy corporates doing business in South Africa to set up shop on the island.

The treasury last week announced that the new treaty between the two countries had been gazetted and will be applied from January 1 next year. It is in line with international best practice to tackle tax abuse and deals with, among other issues, the treatment of dual residence of companies and withholding taxes on interest and royalties, the treasury said.

The new regulations are intended, among other aims, to make it harder for companies to pay taxes where their money is not earned because of a lower or no-tax regime.

Mauritius is often described as a tax haven because it levies little to no tax. It has attracted a great deal of foreign funds because of its ultra-low effective corporate tax rate of 3%. There is also no capital gains tax and no withholding tax on dividends. In contrast, South Africa’s effective tax rate in some sectors can be as high as 28% for corporates.

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development reported flows of $1.4-trillion in and out of Mauritius in 2013. In a 2011 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report on Mauritius, the four pillars of the Mauritian economy were identified as agriculture, manufacturing, tourism and financial services, at 4%, 19%, 9% and 11% respectively of Mauritius’s gross domestic product. Offshore activities represented 3% of the nation’s GDP and “probably 5% when taking into account indirect benefits”, the report said.

In a report on base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS), published for comment by the Davis tax committee in December last year, it was noted that South Africa is a major trading partner of the island and invests heavily in various sectors of the Mauritian economy.

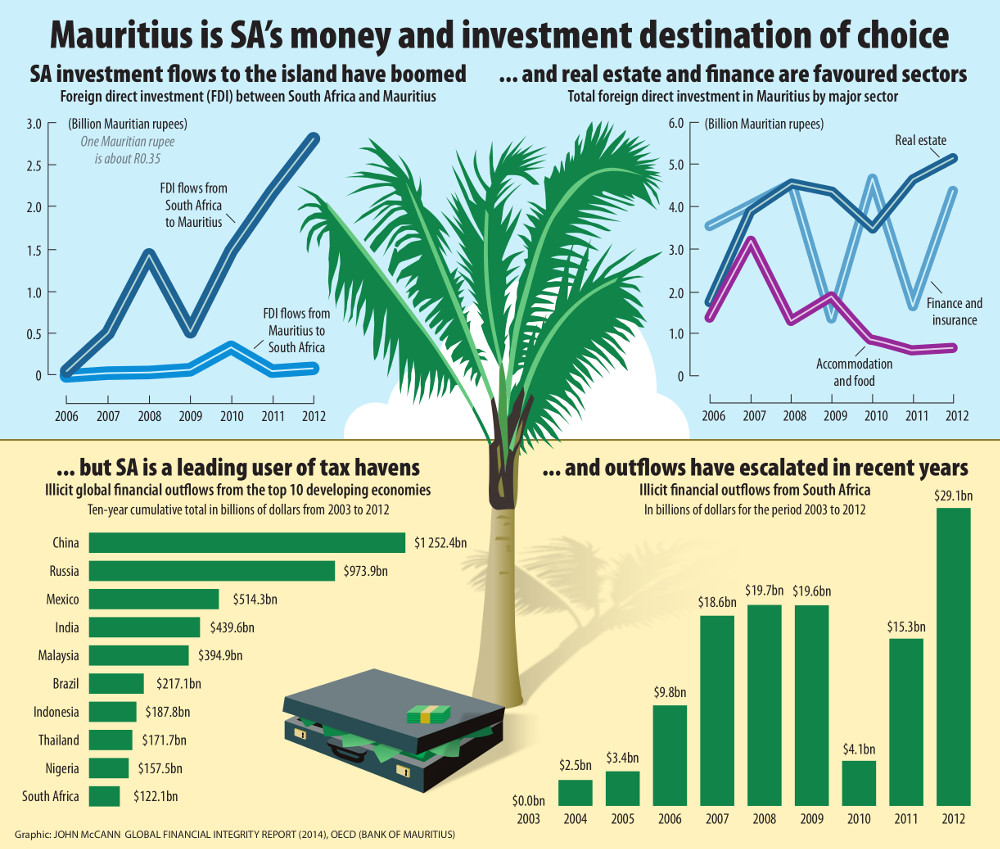

South Africa’s foreign direct investment (FDI) in Mauritius over the past six years has grown so significantly that South Africa is the third-largest single foreign investor after France and China.

Cash flows

Flows from South Africa to Mauritius grew from R35.5-billion in 2006 to R53.5-billion in 2009, although flows from Mauritius to South Africa were flat, at about R6-billion, throughout that period.

“This is indicative of the ease of doing business as well as the attractiveness of the Mauritius tax regime,” the Davis report said.

The report, which anticipated the new treaty, said its provisions could see these flows reverse “as it will not be beneficial for South African companies to use Mauritius as a gateway for sub-Saharan African expansion … The double taxation impact could result in decreased South African FDI into Mauritius – albeit minimal.”

An African Union report on illegal financial flows released last year said the high exposure of individual African countries to “most notably Mauritius” was an overall driver of illicit financial flows worldwide. “Its [Mauritius’s] operation as a relatively financially secretive conduit results [not only] in high exposure for itself, but also for other countries across the region,” the report said.

Treaty shopping by corporates to exploit loopholes to avoid paying tax is not illegal, but is increasingly considered unethical because poor governments continue to miss out on revenue from mega-profits earned within their borders.

A prominent change, detailed in the new treaty between South Africa and Mauritius, is the introduction of a tie-breaker clause for when an entity (“a person other than an individual”) is resident in both nations.

A lack of clarity about in which state a company is liable for tax can result in double non-taxation. Tax agreements between states are designed to prevent an individual from being taxed on the same income by two different countries, but these treaties are often abused and instead can result in the individual not paying tax in either nation.

The new treaty’s tie-breaker clause allows tax authorities to agree mutually on where the tax is owed.

Released last week, a memorandum of understanding between the South African and Mauritian tax authorities sets out the factors they will take into account in deciding the country of residence.

These include the country in which board meetings are mainly held, where executives carry out their activities, where their headquarters are and where their accounting records are kept.

When the tax authorities cannot agree, the company or entity will not be entitled to any tax relief or exemption allowed for by the treaty.

The treasury said the agreement had been proposed as the main test of the OECD’s model, which is part of the BEPS initiative taking place under the guidance of the G20, which includes South Africa.

No obligation

The Davis report said there was no obligation on the competent authorities to reach an agreement on the residency of an entity and “it is probably practical to assume that the chances are remote of reaching agreement swiftly or even at all”.

This was because the competent authority of Mauritius, for example, would not, in principle, have an active interest in coming to a mutual agreement where this would involve losing its taxing rights to South Africa, the committee said.

Tax experts say the question of dual residence should not have much of an effect because companies should already adhere to the requirements they will be tested against.

The agreement might have an effect on capital flows as a result of withholding tax, the situation in which tax is deducted in advance from earnings to pay what is owed, usually on interest or royalties.

The Davis report said, because Mauritius had negotiated better benefits in its tax treaties with some African countries than South Africa had, South African companies often routed investments into the continent through the island economy.

The old tax treaty had no withholding tax. But the new tax treaty includes tax on interest earned in South Africa.

The result is that South African lenders to Mauritian borrowers will not be negatively affected by the change, as suggested by the tax committee’s report, but Mauritian lenders to South African borrowers will be affected.

Portal for investment

According to Aneria Bouwer, a partner at Bowman Gilfillan, the amendments were not that negative for South African companies using Mauritius as a gateway for foreign investments, but it did make Mauritius less attractive as a portal for investment into South Africa.

Bouwer said it did not necessarily mean foreigners would be better off by investing directly into South Africa because the withholding tax rates in question were still lower than the usual South African withholding tax rates.

Wolfe Braude, the founder of research firm Emet Consulting, said Mauritius had been quite open about the fact that it was diversifying its economy and becoming a financial services hub, and one way of doing that was to offer lower tax.

“It certainly has elements of a tax haven but this is not illegal globally. It’s nothing worse than what Bermuda and the Netherlands offer.”

Braude said the changes in the new treaty were not radical. “They don’t substantially compromise the private sector, but it makes it less attractive for companies to abuse the dual taxation agreements. It will affect those who deliberately set up to avoid tax.”

Braude said the treaty amendments occurred in the context of the work the G20 and OECD were doing on tax avoidance.

“Tax havens have been in existence for decades. There have been complaints about it, but no global move to restrict their movements. Now governments have woken up to the fact that these things are a serious problem.”

He said the move was driven by the fact that, since the financial crisis, governments were finding fiscal gaps in revenues and, because of shrinking GDP, tax avoidance had become a serious issue.

“It is highly unlikely we will meet our millennium development goals, or address globally inequality in absence of shutting down tax havens,” he said.

South Africa is renegotiating treaties with a number of other countries, including the Netherlands and Luxembourg.