THE GIRL FROM HUMAN STREET: GHOSTS OF MEMORY IN A JEWISH FAMILY (Bloomsbury) by Roger Cohen

A young man, a captain in the Dental Unit of the 6th South African Armoured Division, opens this extraordinary book. It is 1945, Italy, and he comes eye to eye with the body of a German soldier his own age: it’s an encounter that opens up a litany of psychological and spiritual demons, causes and contradictions that contribute to the human condition.

It is on this conflation of beauty and horror, life and death, logic and illogic that Roger Cohen’s book focuses. These stories upon stories, premised on letters, diary entries and contextual research, define the texture of a book that is so beautifully constructed and honed that you want to read it slowly to savour it.

But you don’t: the words flow with a simple unpretentiousness, leaving you touched and changed – and wishing that Cohen’s family presented more detours that required his focus.

The central concern of this book is a tribute to Cohen’s mother, June, the girl from Human Street.

She a woman who existed in the cusp between South Africa and Britain, and in the bottomless pit of depression that began postpartum and took her through all the harsh indignities of treatment by electro-shock, de rigueur at the time, as well as isolation and silence on the part of her young family.

Although there is a detailed and empathetic account of June’s illness, the book is about so much more, affording June an inimitable, dignified presence in Cohen’s life, and enabling her to be a prism through which he contemplates the world and the context in which he has become who he is.

This book skirts self-indulgence. We are exposed to personal snippets from Cohen’s diaries and, instead of being exposed to great clumps of anecdote, we are taken on the journeys of other relatives or contemporaries.

Cohen writes with a developed perspicuity and poetry, his language richly blending everything from historical fact to private story.

From the outset, and with the adventures of his uncle Bert, a sense of universality is cast over the characters that might make you think of your own.

Furthermore, the narrative lines of this book are cast in elegant parabolas that dovetail and segue. You meet characters again, or their children, or grandchildren, as the work unfolds.

Writers as diverse as Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai, Turkish novelist Orhan Pamuk and English poet Robert Frost are present, among others, in this remarkable text.

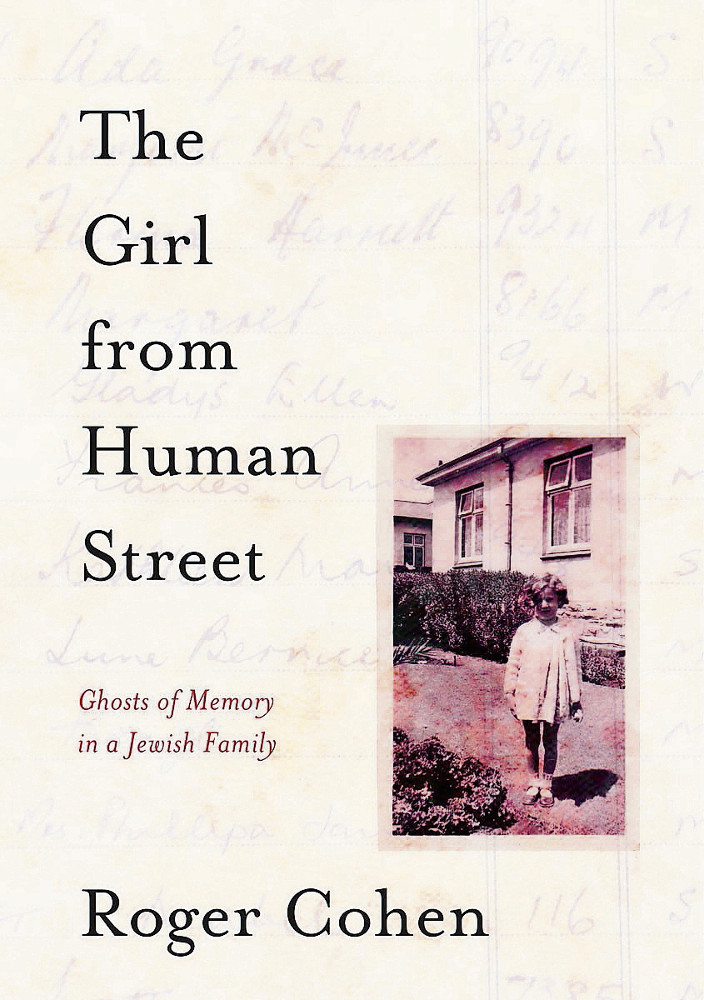

Cohen’s engagement with photographs in this book lends the experience of reading it greater charm than it would have without them. The photographs are drawn from many sources: his parents’ wedding portrait, a class photo of his mother and her classmates at the Barnato Park High School in the 1940s, and other formal portraits and holiday snaps.

Not all are directly illustrative of events described in the book – the images appear to crop up randomly, not unlike mementoes slipped between pages nonchalantly, but with love.

When Cohen engages with the photographs, there’s a level of interpretation in his words that allows you to look at the images on several levels. It’s a device Cohen doesn’t use enough, but it cements a real reflection on the value of the individuals immortalised in Cohen’s history.

Ultimately, it is Cohen’s sensitive, grown-up focus on the palpable reality of loss and how it serves to uproot as much as it does to unify, to destroy as it redefines, that is this book’s richest anchor. Loss conjoined with madness, or a loosening grip on one’s emotions, is a thread that runs under the surface and in the genes of this family.

And loss is conjoined with shame that becomes a Jewish South African dialect, as it travels through history, touching everything from the Holocaust and apartheid to how values concatenate so roguishly in any reflection of Israeli politics.

Cohen, a columnist for the New York Times and, before that, a foreign correspondent, has the know-ledge and ability to raise the lid on a political Pandora’s Box like Israel, and to describe all that he sees there in its sense of contradictory, often ugly values. He’s sufficiently an outsider and sufficiently an insider to have an opinion that matters.

He argues that it doesn’t augur well for one country to have a day of celebration and a day of catastrophe honoured at the same time, as Israel does. He casts a solemn eye over the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement, understanding its merits and failings, and looks as critically at the South African and American Jewish tendency to view Israel as above criticism.

The Girl from Human Street is one of those books you need in your life: it engages with the multiheaded bizarreness that it takes to be a human being in this world. Governed and formed by boundary, it is a compelling read. It is the kind of book that leaves you with a hollow sense of loss because Cohen’s words ring with such freshness and sanity, you want more of them in your head.