Dominionville became a ghost town when 4 000 people lost their jobs after Uranium One closed the mine

A truck trundles along the wide gravel road, spraying water to dampen the red earth. Vanishing behind a new and growing pile of mining rubble, it leaves behind it a silent valley and some hungry sheep.

A few minutes later the rumble of a large mining truck ensures the peace is throttled. Looking new with its gleaming black and yellow paintwork, it crosses the public farm road with a load of rubble from the world’s fourth-largest uranium mine.

The dampened road should not exist. The mine that it leads to – Shiva Uranium’s gold and uranium complex – has been operating under the management of the politically connected Gupta family for nearly four years without up-to-date permits for many of its environmental impacts.

This fact is contained in documents prepared for Shiva and submitted before the listing of the mine’s holding company on the JSE in November last year.

Listed mining companies have to disclose any possible liabilities, including environmental transgressions that could carry a fine. In Shiva’s case, this is contained in a “competent person’s report”. The 300-page report details every aspect of the Shiva Uranium mine, including several ways in which it was not complying with legislation at that time.

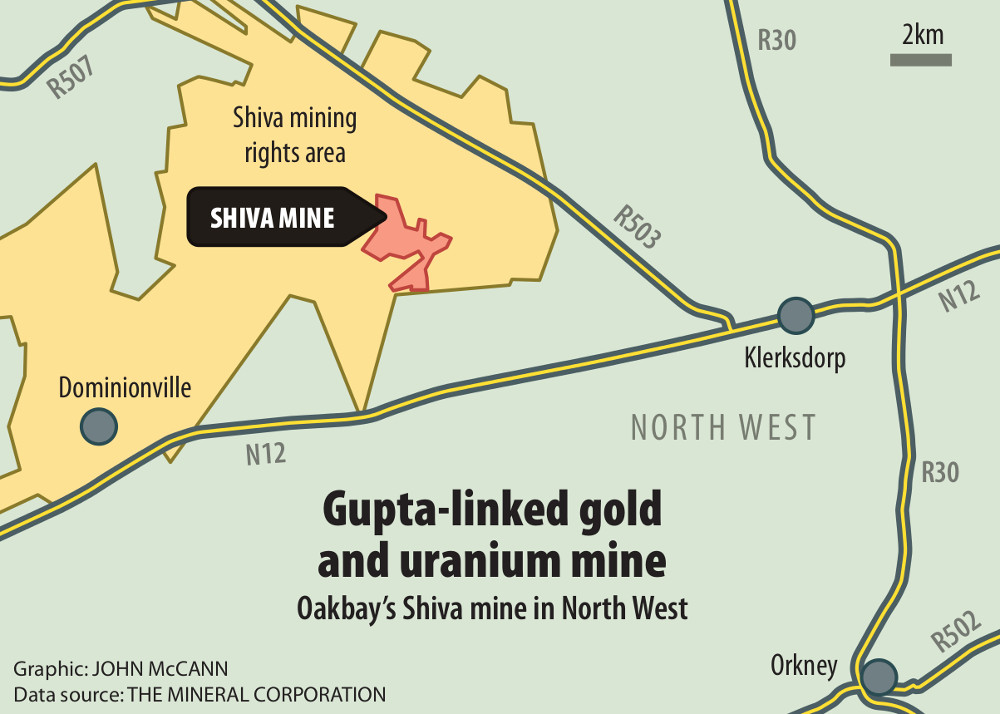

Shiva is the successor to several mining companies at the North West site that have tried to turn a profit from the vast gold and uranium deposits that lie just beneath the rocky and hilly grazing land.

Starting in 1886, the site, about 20km southeast of Klerksdorp, has been dug up by a succession of companies. The last one, Uranium One, ran a gold mine alongside its uranium operation.

It listed it as the world’s fourth-largest mine for the key ingredient for nuclear weapons and power plants. But the Canadian-listed company put the mine on hold in 2008. Four thousand people lost their jobs. The local town of Dominionville – its grid-pattern dirt roads and small red brick houses creating a community for mine management – lost its main source of income. The large town hall, where dances and weddings were held in the mine’s heyday, is now overgrown with weeds. Its missing roof echoes a pattern repeated throughout now-derelict Dominionville. Only a few houses stubbornly cling on, with neat lawns and greenhouses packed with the fruit of small projects to earn money.

Sections of the gigantic gold and uranium belt in Dominionville have been mined without the required permits. (Madelene Cronjé, M&G)

Two years after mining was put on hold, the local operation was bought by a partnership between Oakbay Investments, owned by the Gupta family, and the Indian-based Action Group. The two created Oakbay Resources and Energy, a holding company for Shiva Uranium.

A quarter of Shiva is owned by a black economic empowerment group, which includes President Jacob Zuma’s son Duduzane’s Mabengela Investments and the Umkhonto weSizwe War Veterans’ investment arm.

In August 2010, it started producing gold again, and six months later it produced its first uranium. Since then it says it has mined about 2.6-million tonnes of ore.

Last November, Oakbay listed on the JSE. Contained in the listing was a specialist report that said mining operations had started without some of the required environmental permission. It found “inconsistencies between the existing and the planned future mining operations, and those described within the approved environment impact assessment and environmental management plan”.

This meant the mine was carrying out work that was outside what was allowed in the environmental plans.

The specialist report said the only environmental authorisations given to the plant were for the “installation and utilisation of treated sewage effluent”. These had been granted in the early 2000s. At that stage, gold mining was taking place only in underground shafts, a fact explicitly noted in the Oakbay listing announcement.

But in its latest annual report, the company now talks about its “open-pit gold operation” doubling output to 200 000 tonnes of ore a month this year. The listing points to the company not having all of the required permits: “The most significant of which [inconsistencies] being the open-cast gold mining activities.”

To get around the fact that mining had started without legal authorisation, the competent person’s report recommended that Shiva apply for a loophole in environmental legislation – a section 24G rectification. This allows companies that have started operating without a permit to pay a fine for doing so, and to fix the damage while continuing operations.

Environment legislation allows for companies that do not do this to be fined up to R5-million and for their directors to be sentenced for up to 10 years in prison.

Idwala Coal in Mpumalanga, also owned by the Guptas and Duduzane Zuma, applied for a section 24G. According to its own submission, Idwala Coal had diverted a river and a road, mined without a water licence and destroyed a wetland.

Oakbay’s listing gives several cases where authorisation would be required: for the transformation of more than 20 hectares of land; for the construction of haul and access roads; and for the emissions coming out of the processing factory.

And, although a general water use licence exists for the overall mining site, the listing says one “may be required for activities at the Afrikaner Leases gold section”. This is the site of the old underground mine, which has since become an open-cast gold mine.

The cost of rehabilitating the mine when operations cease is also reflected on the company’s books.

The mining Act requires that companies set aside, and continually update, the money required to rehabilitate the area once operations stop.

The Oakbay listing says the total rehabilitation cost would amount to R161-million. Instead, the report says: “The current value of the Guardrisk Insurance policy held by Shiva is R62-million.”

The environment and minerals departments did not respond to questions, but Elsabe Booysens, spokesperson for Oakbay Investments, said in response to questions that the mine had submitted an updated environmental management plan in 2012 as part of a wider Section 102 application to update its mining permit.

This took into account the “possible risk areas” that would subsequently be identified in the Competent Person’s Report in 2014. But it had not been approved by the time this report was finalised and used as part of the JSE listing. That approval only came in February 2015, she said.

“The Shiva Mine opencast mining operation is being conducted with the required environmental approvals.”

The suggestion that a Section 24G rectification be applied for was just that, she said. “The report does not recommend that Shiva Uranium apply for a rectification in terms of Section 24G, but rather poses the question that rectification may, under certain circumstance, be required.”

Given the approval this year of the updated, this was not required, she said. “The company takes its corporate social responsibility seriously, especially those relating to environmental matters.”

Shiva also receives regular inspections from the water and mineral departments and no concerns had been raised, she said.