Detainees await tuberculosis testing at Pollsmoor

It is 7am. The waiting area for family members hoping to visit their loved ones detained in the remand section of Pollsmoor Maximum Security Prison is packed. Mostly women, they sit huddled next to each other on wooden benches, clutching bags of clothing, food and blankets for their brothers, husbands and sons.

A man with a brightly coloured tie stands on a bench and proclaims loudly: “Thy kingdom come, blessed saviour!” When his sermon is finished, he goes around the room and, to everyone’s bemusement, shakes hands. His performance is the only entertainment the relatives are offered during their long wait.

At about 10am, a warder shouts out the names of prisoners. The visitors can then walk to the remand section, where there is another three-hour wait. When the door to the visiting area finally opens, there is a mad scramble to get in. Prisoners are seated on the other side of a glass partition, craning their necks to see a familiar face. A 30-minute chat is what the families are allocated after their six-hour wait.

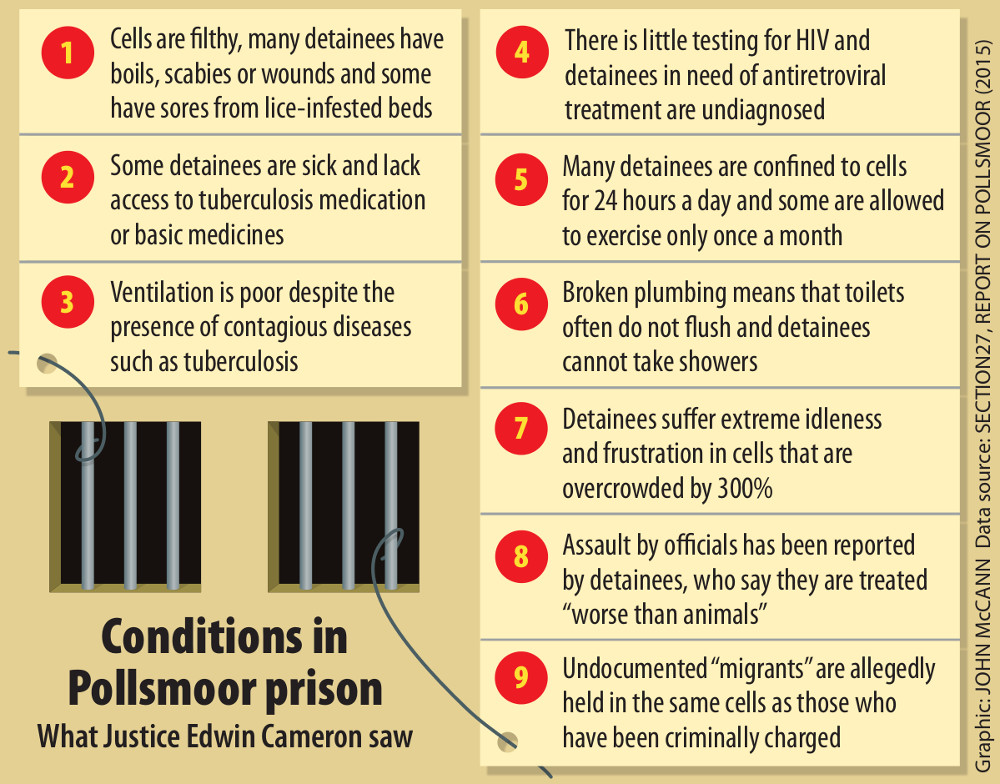

The long wait and the overcrowded visiting areas are a reflection of the severe problems the prison faces. With the population in the region of 300%, Pollsmoor prison has the highest overcrowding rate in the country. This is exacerbated by too few staff; Constitutional Court Judge Edwin Cameron recently noted the chronic staff shortage after a visit to the prison (see below).

The shortage of personnel also means there are not enough correctional officials to enable inmates to exercise. One of the detainees who spoke to Cameron complained: “We’re human beings, but we’re treated worse than animals.”

Inmate Clayton Paulse echoed that sentiment to the Wits Justice Project during its recent visit to the jail.

“The last time I was let out of my cell for exercise was two or three months ago,” he said. “There is nothing to do; there are no educational programmes and no library.”

It is near impossible to hear what Paulse is saying, as the din of chatter in the room drowns out his words and the intercom barely works.

We also learned that prisoners in the remand section sleep on the floor or are forced to share lice-ridden mattresses, and up to 70 men have to share one broken toilet and a shower with no hot water.

The next day, we visited Robert*. After his conviction in April, he was moved to the sentenced section of the prison. Hopes of a shorter waiting period at this part of Pollsmoor are dashed when a steady queue builds up at dawn, as the first sun rays pierce through the grey clouds above Cape Town. Six hours later, Robert appears on the other side of a chipped and grimy cubicle.

Robert’s parents live in a run-down house in Mitchell’s Plain. “I get up at 4am to catch a taxi to Pollsmoor, I get there at 6am and then have to wait another six hours,” says his father, who wants to remain anonymous to protect his son’s identity. “We haven’t seen him in three months because we can’t afford the R80 taxi fare. I live on a disability grant.”

His son struggles to get by in Pollsmoor. “There were not enough guards to take me to the doctor,” Robert says in reference to the remand section of the prison. “I hear voices in my head and if I don’t get my tablets, the voices get louder and they keep me up at night.”

After becoming increasingly paranoid, Robert broke a glass window and threatened to stab a fellow inmate. He was then placed in the hospital unit, where he claims he still didn’t receive any medication.

Robert is yanked from his chair mid-sentence, 10 minutes after the start of the visit. A warder grabs his arm and waves with it, to signal that the visit is over. “Come back tomorrow,” he mumbles as he pushes Robert back to his cell.

* Not his real name

Left to fester behind bars

Constitutional Court Judge Edwin Cameron has slammed inhumane conditions at Pollsmoor prison. In a report on his visit to the jail in April, he writes that he is “deeply shocked” by the “extent of overcrowding, unsanitary conditions, sickness, emaciated psychical appearance of detainees, and the overall deplorable living conditions were profoundly disturbing”.

In addition to the chronic staff shortage, there is a high employee turnover rate and, generally, their concerns are not recognised and nor are they promoted.

In a prison known for its brutal and violent prison gangs, this has, according to the Police and Prisons Civil Rights Union (Popcru), led to “untenable stress levels” among staff members.

Cameron noted the poor state of the prison’s healthcare services: “Detainees … were held in adjoining cells or stood along the corridors, some sitting or lying on stretchers on the floor. Some detainees displayed rashes, boils, wounds and sores to us,” the judge observed.

The doctor on duty told the judge his concerns. “He lacks essential supplies and medicine – in particular bandages, injections, gloves, drips and essential ointments to treat skin infections.” The pharmacy was either out of stock or had a shortage of tuberculosis (TB), hypertension and diabetes medication.

Department of correctional services regional commissioner Delekile Klaas, who accompanied Cameron on his visit, stated that the inspection demanded “immediate responsive action”. A departmental action plan to address the deplorable prison conditions is attached to Cameron’s report.

Several civil society organisations – including Sonke Gender Justice, Lawyers for Human Rights and the Treatment Action Campaign – reported these serious issues to Klaas in 2014. They informed him that 200 inmates had to sleep on the floor and, in some cases, on a wet floor because of a leaking roof. At the time, Klaas denied the allegations and accused the organisations of ill intent. “It is a malicious campaign … a publicity stunt,” he responded.

It is not clear why the department did not act to remedy the subhuman conditions in the remand section. In 2012 the Constitutional Court ruled that the department had ignored its own regulations and other legal provisions by not curbing the spread of TB.

Constitutional Court Judge Edwin Cameron. (Madelene Cronje, M&G)

Dudley Lee, a former remand detainee, had sued the department after being infected with the pulmonary disease. Increasing ventilation in the prison was one simple measure the department could have implemented to tackle the spread of the disease.

Three years after that ruling, Cameron observed: “There were very few windows and insufficient ventilation … The air was stifling.”

An independent correctional centre visitor working for the Judicial Inspectorate of Correctional Services said several inmates had not received their TB medication for three weeks.

The Detention Justice Forum, a group of civil society organisations concerned about detainees’ rights, condemned the prison’s conditions: “There is no excuse for stock-outs of TB and other essential medicines or for subjecting people to lice-infested bedding, 24-hour lock-up and extreme overcrowding. The department has sufficient funds to house detainees in humane conditions; it is ineffective and unaccountable leadership that is causing these abuses.”

Departmental spokesperson Manelisi Wolela said: “The challenge of overcrowding remains high in the Pollsmoor remand detention centre, a matter that is being discussed with partners of correctional services within the criminal justice system.”

He said the department would address infrastructure problems and bolster healthcare services.

Ruth Hopkins is an investigative journalist working for the Wits Justice Project

SABC News reported this week that 4 000 Pollsmoor inmates are to be moved to other prisons after two died from leptospirosis, a bacterial disease spread by rat urine.