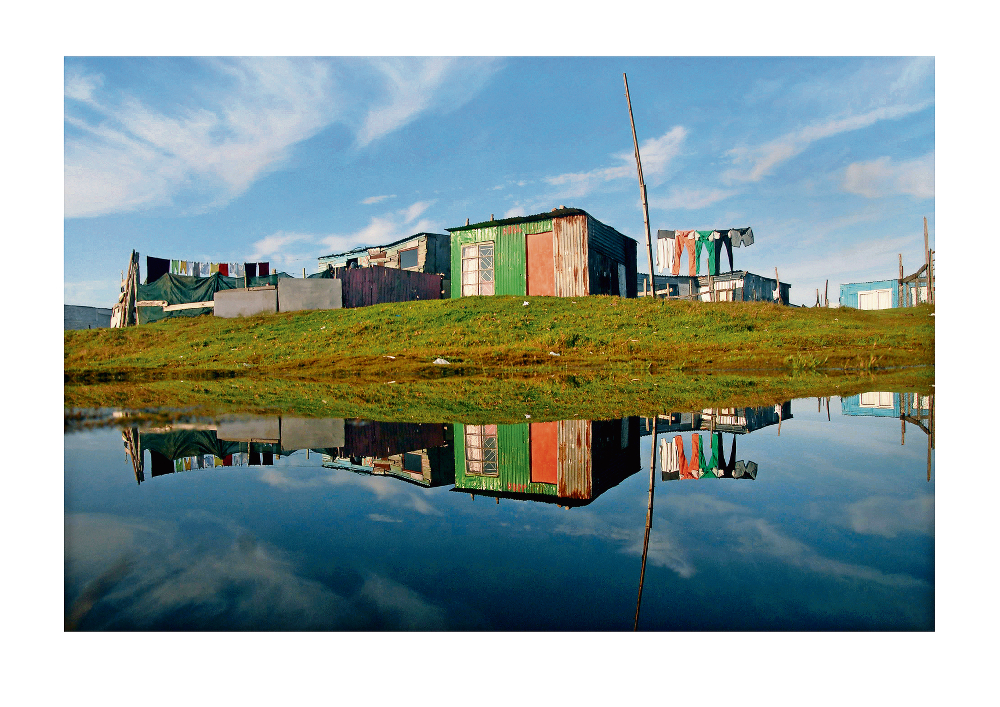

Masixole Feni's 'Crossing over the unbearable canal'

Masixole Feni, an activist-photographer and the 2015 recipient of the Ernest Cole award, lives on the Cape Flats and his winning photo series, A Drain on Our Dignity, documents the lack of proper sanitation in the area.

Of the series, Feni says: “I live at the back of an RDP house in Mfuleni. I experience issues like poor sanitation, access to clean water and flooding first-hand.”

The annual photographic award, given under the auspices of the University of Cape Town, is named after Ernest Cole, a South African photographer who worked in the 1960s and was among the country’s first black freelance photographers. The award helps a photographer to pursue or complete a project from which an exhibition and a book are produced.

These are goals most photographers yearn to achieve but for many they remain an elusive dream. It is expensive to develop, print and exhibit their work and not easy to find a publisher willing to issue a photo book. An award like this goes a long way towards boosting a photographer’s professional development.

“I feel quite lucky to be working on a photo book without a proper qualification in photography,” Feni says.

He did not study photography formally because he could not afford it. Everything he knows on the subject he learned from the online Icon Photography School and Iliso Labantu, a photography collective whose members include Sipho Mpongo of the Twenty Journey photographic project that documented South Africa two decades into democracy.

It was while Feni was involved in these projects that he sold his first image, aged about 18. On the day he took the photograph in question, he had been in Mfuleni at the Sakhumzi orphanage, where he had spent much of his younger life. An acquaintance who knew he took photographs dragged him to the scene of a murder. He took the image with a disposable camera and, in a moment of tragedy, he became a photographer.

He wears his heart on his sleeve

Mfuleni is about 40 minutes on the outskirts of Cape Town. To get there, one must drive away from the highways and traffic and just keep going and going. On the way there, the city topography of tall buildings and electricity pylons rising to the sky gives way to hilly mounds and clear skies, prompting one of the taxi passengers to remark that it resembles the Eastern Cape more than it does Cape Town. It is once one is inside Mfuleni that it becomes clear that the knolls and clear skies are a façade: like any other township, Mfuleni functions with systematic pandemonium.

‘Chrystal fine reflection in the deluge after the rain’ (Masixole Feni)

On the day we meet, there was no trace of wind until a plastic bag floated past, having taken all the air currents for itself. Though he has won the Ernest Cole award, Feni wants to work far away from the limelight, documenting what he sees as an abyss camouflaged by democracy and the rainbow nation. He is a photographer who wears his heart on his sleeve.

His favourite photographers include Santu Mofokeng, Paul Weinberg, Cedric Nunn and Themba Radebe. Looking at his photographs, one could have guessed it.

Feni works as a photojournalist for GroundUp, a news website that reports on social justice issues in townships and immigrant communities. His images that accompany the news stories highlight his storytelling skills more than his photographic ability, which is better showcased in his photo essays.

A Drain on Our Dignity, the project that won him the Ernest Cole award, is a testament to his commitment to tell stories about underprivileged people. Sidestepping a question about whether he will ever take lifestyle or fashion photos, he tells me about his plans to give back to his community and mentor children on how to tell stories through images.

“One thing I would like to do is maybe teach photography to other children from vulnerable backgrounds who might find it hard to discover the arts in their hearts,” he says. “Like me — I was never aware that I could be a storyteller.”

Feni takes selfies, but not in the conventional sense. When you encounter the photographer in the images he takes, he is inserting himself into a photo dissertation of class division and what he sees as the spectacular failure of democracy. Masi, as he is known to those close to him, points his camera at himself in the style of Mofokeng or Mozambican photographer Mário Macilau.

Like the photographers whose work he admires, his pictures reflect a deep caring for the subjects and the stories he is telling.

Feni first found photography at the orphanage. It came to mean so much to him that, when they stopped offering photography classes, he saw no reason to stay there. He has never wanted to do anything else with his life, and it is his unwavering love for photography that has seen him through some tough times.

If nothing else, a difficult life teaches one patience and resilience. Losing his parents when he was young, growing up in one orphanage after another, getting kicked out of two of them, sleeping on people’s floors, renting a shack with a friend in Nyanga, smoking weed, doing drugs and subsequently finding himself — these trials have informed much of his photography.

Feni’s photographs showing the lack of sanitation in Cape Town townships do not reveal anything new to us; they point out the everyday reality of the poor. We are aware of the country’s class divide, with the poor having to contend with burst sewage pipes, leaking roofs, young children playing in foul water and shacks standing on the edge of polluted canals.

But it is clear that his images are a form of protest, constantly poking a finger at the neglect of the poor while others live lives of privilege.

In one of his photos, young children walk past a filthy water canal that separates a dense row of shacks. In another image, which captures what Feni’s photography is about, a man throws excrement at the convoy of Helen Zille, then premier of the Western Cape.

Feni speaks with assurance, saying what he needs to without wasting a word. His images, too, are considered and measured; nothing is in the frame that need not be there — though some could be better framed.

The Ernest Cole award comes with prize money of R150 000, with R100 000 going towards an exhibition and R50 000 to logistics.

Feni plans to travel around South Africa to document the living conditions of the poor. “I will be going to the Eastern Cape, Limpopo and possibly KwaZulu-Natal, to take images that speak to service delivery,” he says.

Feni admits he is far from where he wants to be. He would like to own a better camera as well as a “point-and-shoot” camera, so as not to draw attention to himself when he is taking photos in dangerous areas. He also wants to study filmmaking, “because there is a much broader audience in television than in print and online”.

When we meet, his camera is in for repairs. When he speaks about it, his expression is the same as when he is talking about his newborn son. Considering the role photography has played in his life — much like a protective guardian angel — this love for his camera is understandable.